Kevin Costner has been on a real tear of late; between last year’s Man of Steel, and the early 2014 one-two punch of Jack Ryan: Shadow Recruit and 3 Days to Kill, he’s been popping up everywhere, and with increasing frequency. Draft Day, then, feels like an inevitability; it was only a matter of time before Costner’s comeback campaign involved him in a modern sports-centered project, all the better to exploit his Bull Durham and Field of Dreams iconography. If audiences loved the combination of Costner and athletics in 1988 and 1989, why wouldn’t they love it now? (The less said about Tin Cup, meanwhile, the better.)

Returning to the uplifting sports narrative well seems like good business sense, but the tenor of these movies has changed, and so has their appeal. Sure, occasionally a 42 comes along and plays around with archetypal tropes, with middling success, but Moneyball‘s critical and commercial success in 2011 has opened up the door to new perspectives on a well-tread genre. Draft Day fits more alongside that film than the sports hero yarns of Costner’s past, and while Costner himself makes the transition quite admirably, the entire affair feels frustratingly uneven.

Draft Day revolves around the final twelve hour stretch leading into the NFL’s annual draft, in which college players with professional aspirations tirelessly sell themselves to major league coaches. Their goal is NFL super-stardom; they’re aching to make the cut and play the game on a national stage. But the story here isn’t about them. It’s about the people calling the shots, making the decisions that will irrevocably alter the lives of these young men. Draft Day doesn’t give a good goddamn about the players, instead putting all of its emphasis on the crotchety old-timers who shape the teams and sign the paychecks.

On paper, that doesn’t sound like an appealing premise, but it’s slightly more palatable in practice. If there’s one major takeaway to Draft Day, it’s that the behind the scenes of the NFL functions like a relentless meat grinder, driven by wheeling and dealing at the expense of compassion and humanity. Maybe that’s a soft sentiment for a hard game, and in truth, Ivan Reitman doesn’t really have much patience for that kind of bathos anyways. His film sets aside the dreams of its ambitious youths almost entirely, instead honing in one man’s struggle to cope with the legacy of his recently deceased father.

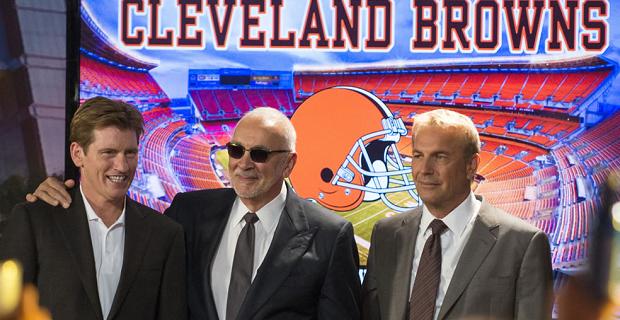

It’s hard to imagine most of this working without Costner’s anchoring, authoritative presence. As fictitious Cleveland Browns coach Sonny Weaver, Jr., Costner brings authenticity to the proceedings; he can play decent men muddling through loss and feelings of inadequacy against a sports backdrop in his sleep. Sonny has a lot to live up to, courtesy of his legendary dad’s contributions to Cleveland football, and everybody – his mother (Ellen Burstyn), his coach (Denis Leary), his boss (Frank Langella, perpetually bedecked in sunglasses for intimidation factor), his girlfriend-cum-salary lawyer (Jennifer Garner), the fans – is on his case about investing smartly in the Browns’ future.

That’s Draft Day‘s hook, though: Sonny wants to draft his team, his way, to hell with the rules and expectations. The throughline here is that you’re better off trusting your gut than just doing what you’re told. Taken from that perspective, Draft Day actually provides compelling drama, as every move Sonny makes sidesteps predictability while ruffling as many feathers as possible. He doesn’t want to draft Bo Callahan (Josh Pence), the obvious “best” pick in a sea of viable candidates; he actually wants to draft Vontae Mack (Chadwick Boseman), rough-hewn but passionate. In other words, Sonny wants to carve his own path.

That’s Draft Day‘s hook, though: Sonny wants to draft his team, his way, to hell with the rules and expectations. The throughline here is that you’re better off trusting your gut than just doing what you’re told. Taken from that perspective, Draft Day actually provides compelling drama, as every move Sonny makes sidesteps predictability while ruffling as many feathers as possible. He doesn’t want to draft Bo Callahan (Josh Pence), the obvious “best” pick in a sea of viable candidates; he actually wants to draft Vontae Mack (Chadwick Boseman), rough-hewn but passionate. In other words, Sonny wants to carve his own path.

If Reitman had stuck with that as Draft Day‘s focal point, he’d have had a leaner work on his hands, denuded of filler. There’s something attractive about the spirit of Sonny’s stubbornness, but his rebellion often gets swallowed up by extraneous flimflam lurking in the margins. Too often, that excess seeps into the narrative, distracting from Sonny’s attempts to broker the right deals while upholding his integrity and mollifying the peanut gallery. Reitman doesn’t accord proper care to dramatizing either the judgment calls Sonny makes or the people they impact. As a result, we become distanced from consequence and meaning, even when Sonny’s brilliant strategy comes together in the climax and everyone gets what they want.

Reitman nearly makes up for Draft Day’s pat contrivances with technique; he directs the bejeezus out of the film, split-screening conversations while sliding the frames around like he’s rearranging pieces in a tile puzzle. Sometimes this whiz-bang craftsmanship pays off, lending propulsive vim to material that’s arid by nature, and in these moments, Draft Day holds us in its thrall with unexpected ease. It doesn’t matter if you follow football or not – Reitman makes the shop-talk and macho tete-a-tetes not just interesting, but gripping, at least until he doesn’t.

Maybe there’s only so much chatter about stats and trades that a movie like this can sustain. On the other hand, maybe it really is possible for there to be too much of a good thing. Reitman goes so above and beyond with his De Palma emulation that after a point, it feels like he’s just lost control of the wheel. Or maybe he’s just trying to gloss over his film’s weaknesses. Character is inconsequential to Draft Day, and all that matters in the end is football. Like Sonny, Reitman can’t easily make up his mind; unlike Sonny, Reitman never quite figures it out.