In the hollow world of Yorgos Lanthimos’ The Lobster, society forces people to be with a romantic partner. Should you find yourself without a significant other, you check into a hotel where you have 45 days to find a lover. If you don’t succeed, you are turned into an animal. Everyday you have an opportunity to hunt loners who have runaway into the forest. For each one you capture, you are rewarded with an extra day to find love.

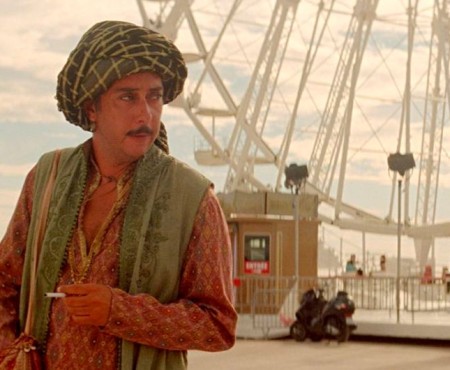

David (Colin Farrell), who has selected to become a lobster in the unfortunate circumstance he fails to attract a mate, checks into said hotel, and befriends two fellow male suitors (John C. Reilly and Ben Whishaw). The hotel staff run a tight ship, punishing those who break the house rules (no masturbating or else your hand gets burned in a toaster), and indoctrinating their “guests” with monogamous-positive propaganda.

Lanthimos, acclaimed for his 2009 film Dogtooth, and less so for his most recent feature, Alps, is one of the directors associated with the Greek New Wave that has burgeoned over the last 10 years. Less interested in people than his compatriots such as Athina Tsangari (an equally strange but far better filmmaker), Lanthimos depends entirely on overdrawn concepts and overwrought allegory. A horrible offender in this regard, The Lobster is all concept, no cinema; the type of one-note alternate reality metaphor that can carry short stories but rarely feature films.

His rigidly composed mise en scène is devoid of vibrancy, which is matched by the cold, mannered performances. The result is a cinema without pleasure, without humanity. Fans of Dogtooth may find the sheer absurdity and vacuum-dried sense of humor here amusing, but if Lanthimos has something he wants to say I imagine it would seem far less interesting were it not covered up with layers of superficial posturing.

In Dogtooth, the absurd conceit of the film was one imposed on characters with in the diegesis, placing it within two worlds: our own and the one manufactured by the parents. But the conceit here is a harder pill to swallow, as it seems at once too enveloping and too diaphanous. At times the film comes close to poking fun at itself, but that’s also when The Lobster is at its most disingenuous, as one can sense the film’s arrogance at every turn.

I admit to a fondness for Farrell’s effort here (gut and double-chin included), and in general the cast deserves much better. I fear that Lanthimos may be among the worst and most cowardly sort of filmmaker, the faux provocateur, distracting the audience with the weird, the violent, the sexual—hiding as best he can the thinness that lies underneath.

1.5 stars out of 4.