One of the greatest directors of the last four decades, Hou Hsiao-Hsien’s first feature film since 2007’s Flight of the Red Balloon immediately qualifies as one of his greatest achievements. The Assassin is a subtle, sparing, and at times abstract take on the Wuxia martial arts film as an existential rumination on choice.

Shu Qi plays Nie Yinniang, an expert assassin who has just completed her training, only to fail to kill her target on an assignment after she comes upon him in a moment of compassion with his son. Disappointed in her sentimental decision, Yinniang’s master asks her to kill her cousin Tian Ji’an, to whom she was once promised in marriage before being exiled from her family as a child. Tian Ji’an is now the governor of Weibo, a powerful Northern province that has struck a tricky balance of independence and peace with the Chinese empire. Returning to the place of her childhood, Yinniang encounters a moral dilemma. Weibo’s stability rests in the hands of Tian Ji’an, and both the man and the place, half-forgotten elements of her past, still occupy a place inside of her. And so she must decide where her allegiance lies.

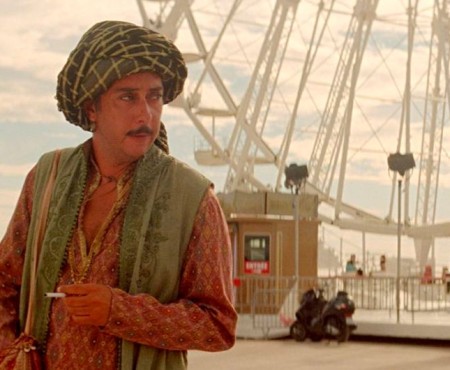

One of the best cinematographer-director pairings ever, Mark Lee Ping-bin and Hou have yet again created a completely singular mise en scène, one so overwhelming that you may find yourself absorbed into the images, to the point that you stop paying attention to the plot (hence, this author saw the film twice to piece it together). Flickering candlelight and a lush palette of rich reds, golds, and lavenders characterize the meticulously detailed interiors. Somewhere between the static, painterly Flowers of Shanghai, and the impressionistic movements of Millennium Mambo, lies The Assaassin. A gently gliding camera dances slowly with the setting, hypnotic and immersive. One stunningly beautiful sequence films a conversation between Tian Ji’an and his concubine as Yinniang secretly gazes on, with flowing, glowing curtains draped between them, softly shifting in the composition, obscuring and framing the characters as their inevitable encounter nears.

Equally graceful, the film’s few and fleeting action sequences are at once elegant and impactful, augmenting The Assassin’s discreet but overflowing emotions. Yinniang’s existential plight is expressed intensely by Hou’s delicate direction. Shu’s presence is commanding and moving, her exquisite features and incredible confidence making her seem invincible and fragile all at once.

Opening on crisp black and white for its prologue, The Assassin moves into color, and briefly, from its 1.33:1 ratio to 1.85:1 for a single sequence featuring Yinniang’s master playing the zither. She tells Yinniang an allegorical story of a bluebird that doesn’t sing until it sees itself in the mirror, causing it to sing and dance until it dies. A jarring and peculiar choice, this transient expansion of the frame, strategic perhaps for framing the instrument in a particular way, also gives special weight to this moment that carries through the following scenes. The choice to kill or not to kill that Yinniang first faces in the opening sequence returns several times. Rarely has the gravity of taking human life been articulated like this in cinema, let alone a martial arts film.

Meanwhile, Tian Ji’an has his own drama in which he finds out he has gotten his concubine, whom he loves, pregnant. His distraught wife, who seems romantically distanced from him, secretly takes action with the help of a mystic. Yinniang, who silently infiltrates Tian Ji’an ‘s palace, observes these narratives, including the fear of an encroaching conflict with the Chinese court.

A work of pure cinema, every shot in The Assassin is a masterpiece in itself. Hou weaves this rich but subdued story in the most mysterious of ways. Dialogue scenes reveal plenty of details, and yet it is the stares and movements of characters that tells their story. The dynamic between an oppressed province and the Chinese empire perhaps evokes Hou’s native Taiwan and its history. The dense peripheral details of The Assassin’s own narrative and its political and historical context magnify the comparably modest dilemma facing its protagonist; the silent decisions of an individual are tied to the fabric of unfolding history. Yinniang’s prudent personal awakening is profound—her choices, and the film’s gestures of beauty synonymous in their poise.

4 stars out of 4

3 thoughts on “Cannes Review: “The Assassin””

Why does the details say it’s from 1965 and directed by some Italian guy?

Whoops! Error with the imdb code

Pingback: VIFF 2015: Hou Hsiao-hsien’s The Assassin | The End of Cinema