There’s something confounding about Mountains May Depart, the latest film from Chinese master Jia Zhang-ke (Platform, Unknown Pleasures). In spite of its promising premise and formal expressiveness, there’s a tonal awkwardness that is hard to pin down as intentional or not. Inappropriately comedic at times, it’s difficult to determine if Jia is working on some level of irony, or at times mishandling the film’s heightened melodrama, and especially the English dialogue that dominates the third act. Divided into three chapters across 25 years (1999, 2014, and 2025), the film begins at the turn of the century, and follows how a love triangle between three friends opens paths of fate across a generation.

Tao (Jia’s wife and muse, Zhao Tao) is a happy-go-lucky young woman, loved by both the modest coal miner Liang and their bombastic pal, Jinsheng. Conflicting desires necessarily drive them apart, leaving Liang alone and heartbroken, while the other two get married, and have a child together named Dollar. When we jump to 2014 it seems that the harshness of existence has played a role in shaping the lives of all three — especially Liang, who has become sick, and who is reunited with his lost love in one of the film’s most moving passages. In the futuristic third part, Dollar becomes the protagonist, and has to cope with a detachment from society that seems inherited from the choices of his parents.

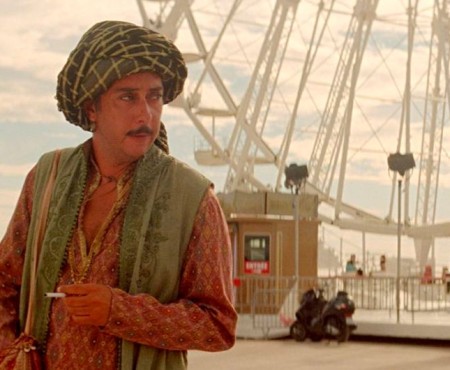

China’s economic state and increasingly globalized society is traced throughout these three chapters, treated as transformative forces beyond the characters’ control. Each chapter is presented in a different aspect ratio, 1999 is in 1.37:1, 2014 is in 1.85:1, and 2025 is in 2.35:1. From the naïve worldviews of the characters in their 20s, the film’s scope expands in the two successive decades, introducing truths of life beyond their initial frames.

The concept is magnificent, but doesn’t quite add up or hold together. Dramatic heft comes and goes in inconsistent ebbs and flows of emotion; a satirical sense of humor pops up occasionally, but is never clearly pronounced; and the film’s increasingly high stakes seem undermined by the haphazard mood in an otherwise meticulously structured work.

If nothing else, the frame-play works as a masterclass on the formal rules of creating compositions for different ratio. As far as the film’s epic sprawl, if you’re expecting the pathos or even the fundamental pleasures of storytelling of Platform (2000), you’ll be left wanting more. Stylistically, the film is a triumph, and stands out from the competition in Cannes with its daring formal choices. A handful of sequences are shot on a cheaper digital format, at times distorting and manipulating the image to unexpectedly beautiful ends.

The way the film settles on no one single character may ultimately take away from the focus needed to earn the emotions on the screen. The 2014 section is the most successful: a rumination on the unfairness of life, the power of choice, and the fear of death. It’s a shame that the payoff in the 2025 section includes laughable line readings and a quirkiness that lands uncomfortably between the gracelessly goofy and the sharply funny. Still, regardless of where one stands on Mountains, it’s refreshing to see Jia move so freely between disparate projects. His last three features couldn’t be more different from one another, and it’s exciting to consider.