Storytelling and its intricate connections to the real world have always preoccupied Miguel Gomes. Our Beloved Month of August (2008) tracks the obstacle-course production of a film set in a Portuguese village, revealing that there’s a lot more drama surrounding the reenactment of the story than the film inside the film would seem to offer. Half of Tabu (2011) meanwhile, is a melodrama set in the not-so-distant past, when Portuguese imperialism allowed for the privileged white to focus more on their burning passions than on the poverty of their servants or social inequities, without seeing ahead of them the imminent political change. Both films have their pleasures and moral provocations, and seem to open the path in their author’s career for a wider tapestry.

Gomes’ six-and-a-half hour long Arabian Nights trilogy, screening in three installments at the Directors’ Fortnight in Cannes, might just fulfill that expectation. All three parts open with an explanatory credit: Arabian Nights does not adapt the homonymous book, even if it’s inspired by its structure. Instead, its subject matter is the current state of impoverishment of the Portuguese people due to the austerity measures of its government.

The first part is aptly subtitled The Restless One and browses several more or less fantastic stories in an iconographic initiation into the directors’ preoccupations. Like several good movies (and many bad ones), the documentary-style beginning of the film features a conflicted director, overwhelmed by the harshness of life, who’s no longer able to find meaning in his art and declares himself unable to think in abstractions. Amusingly, the director is played by Gomes himself and makes his exit from the story by literally running away. The role of narrator is then passed on to Scheherazade (Crista Alfaiate), who is given a fairy-tale-friendly introduction. She’s the threatened bride of a king reputed to murder his wives after the wedding night, and her plan is to pique his interest throughout the night with stories that she leaves unfinished at the break of dawn.

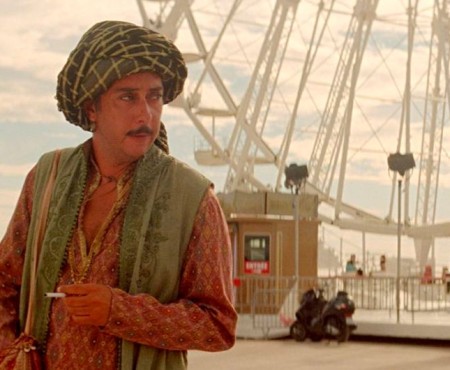

Still, no sooner is the character made to seem familiar than the film steers clear of classical development. Scheherazade stories are beyond the horizon of her period-costume self (not to mention traditional notions of female propriety). For instance, The Men with Hard-Ons is a satire of high-level finance about several bank directors with damaging control over the Portuguese economy who rediscover the joy of living. To be more specific, they encounter a wizard fluent in advertising terminology (Basirou Diallo) who sells them a potion they never knew they needed: an aerosol spray which seems to be a very strong aphrodisiac and has the fortunate secondary effect of making them care less about their economic opportunities. The episode sets the tone for the overall playfulness of the Arabian Nights trilogy: it builds on what seems to be the opposite of an escapist premise (callous characters, trivial ‘transformation’) and makes it into a fantasy-infused relief of a very real desperation.

Being the most dramatically dense film of the three, Volume 1 unpredictably links consecutive fables. The Story of the Cockerel and the Fire depicts an approaching election that gives a rooster its moment of glory, as well as a love triangle involving a firewoman and an arsonist. Inspired by a similar real event, the whole affair seems all the more ridiculous because the three protagonists are played by children and the exchanges are mostly written in text messages.

The last forty minutes of a film, a chapter called The Swim of the Magnificents, includes more (standardly) unspectacular real-life stories and could be seen as reverting to documentary style, except for the fact that the opening sequence looks like a medical exam in the belly of a whale. Volume 1 seems to encompass a fair share of all possible styles of cinema. But there’s plenty more left for parts two and three.

For our review of Arabian Nights Volume 2, click here.