If The Great Dictator strove to save the Tramp from Nazism, Monsieur Verdoux truly destroys him by making him the concentration camp commandant. Aside from a voiceover narration from the protagonist and a disarming photograph, widow-murdering Henri Verdoux’s true introduction is contained in a shot that watches the man cheerfully picking flowers before the camera deliberately pans and holds uncomfortably on a shot of an incinerator rumbling and churning out black smoke, a subtle insertion of Holocaust imagery to instantly disrupt everything one expects from Chaplin.

That slow pan, an economic and deliberate movement that carries ineffable suspense and portent with almost no foundation for its mood, brings Chaplin’s outdated silent techniques startlingly in the present. Like all of the director’s late-career films, Verdoux attains modernity through a paradoxical movement further into the past, particularly to French drawing-room comedy. Verdoux takes place mostly within high-ceiling interiors of the wealthy widows’ homes, their frozen pageantry turned into yet icier horror as Chaplin lets the space in the frame do his work for him. Then, he can make cheeriness even worse, as he does when he delicately sashays about the kitchen setting the table for breakfast before sliding back surreptitiously to remove the setting for the resident no longer capable of taking any meals.

Verdoux’s uxoricidal sociopath seems as far from the Tramp’s warmth as one can possibly be, but where Chaplin elicited the Tramp’s greatest humanism along with his ostensible Jewish lineage in his previous feature, here he brings out the worst qualities that were in the character all along: the duplicity, the illicit methods of money-raising, and the unfailing ability to evade the law’s clutches.

As a penniless scoundrel just trying to get by, these traits are sympathetic, even vaguely heroic when stacked against an unjust system. But Verdoux, who hides behind a self-deluding smokescreen of devotion to an invalid wife and son, perpetuates that very system, a jilted banker who uses most of his blood money to reinvest back into the stock market that took so much with it.

That Verdoux emerges so sympathetic is a testament not merely to Chaplin’s innate magnetism but the skillful maneuvering of the viewer’s complicity in his crimes. Verdoux’s targets are all, amusingly, some of the most profoundly irritating women ever put to celluloid, ornery old bats all engaged in their own schemes or selfish behavior as they succumb to their new beau’s flattery. Yet this also permits some of the richest roles for women in a Chaplin film, divorced from the saintliness and left to plunder comic depths both vaudevillian (Martha Raye’s hilariously unkillable shrew, the most insufferable of the lot) and dark (Marilyn Nash’s Dorian Gray portrait of Verdoux’s self-awareness).

The viewer’s near-compulsion to root for Verdoux as he struggles to put Raye’s Annabella out of his misery grounds the perversity of his final self-defense, a caustic and ironic display that turns Chaplin’s smile into daggers as he compares the outrage over his murders to the condoned atrocities of mass-produced killing that do not merely occur with the consent of society but, in postwar America’s case, are its direct economic foundation. “Numbers sanctify” is the moral an angling reporter receives from the condemned, an inconclusive projection of culpability made only more disturbing by the transformation of the Tramp waddle into a refined walk toward the guillotine.

Technical Specs

Criterion’s 2K restoration is, likely, as good as can be. Print damage is noticeable throughout, from lines running through numerous frames to a general softness around the edges that nearly gives the impression of old silent flicker. The aforementioned incinerator pan even splices in a clearly inferior print (though in some ways the rougher image fits the shot perfectly). Otherwise, the disc looks great, bringing out the way jewelry twinkles in Verdoux’s eye or the deep black levels of shadows that fall menacingly over basic but mannered sets. The lossless audio track proves even crisper, nicely balancing the dialogue with the occasional swells of discordant music.

Criterion’s 2K restoration is, likely, as good as can be. Print damage is noticeable throughout, from lines running through numerous frames to a general softness around the edges that nearly gives the impression of old silent flicker. The aforementioned incinerator pan even splices in a clearly inferior print (though in some ways the rougher image fits the shot perfectly). Otherwise, the disc looks great, bringing out the way jewelry twinkles in Verdoux’s eye or the deep black levels of shadows that fall menacingly over basic but mannered sets. The lossless audio track proves even crisper, nicely balancing the dialogue with the occasional swells of discordant music.

Extras

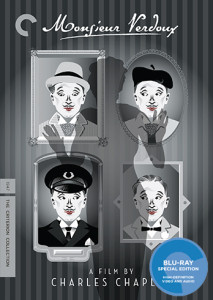

The supplements lead off with “Chaplin Today,” a half-hour documentary that accompanied the film’s previous DVD release from MK2. Providing a decent overview of the social context of the film’s release and the U.S.’s increasing efforts to exile Chaplin, the short is at its best when French director Claude Chabrol gets down to the film at hand and breaks down shots with an awe unfaded from decades of study. A newer doc, “Charlie Chaplin and the American Press” delves deeper into the full history of the star’s rise and fall in the eyes of the media. A few contemporary ads and a dispensable interview with Marilyn Nash fill out the rest of the disc, but far better is the booklet containing reprinted pieces from Chaplin and André Bazin, plus a new essay by Ignatiy Vishnevetsky. It’s a shame they did not (and perhaps could not) reprint James Agee’s legendary, three-article-long defense of the film from the time of its release, but this is just the writer’s desire getting the best of him.

Overall

Chaplin’s true masterpiece joins the ranks of Criterion’s superlative treatment of the artist’s legacy with a strong A/V package and informative extras. Not the Chaplin film most wanted to see roll out of the company next, which makes it all the more valuable and vital a release.