Peruse the comments and posts on The Criterion Collection’s Facebook page and you’ll see a never-ending list of requests from cinephiles. In the last week, 30 people alone requested Todd Haynes’ Carol, which recently came out on Blu-ray in a bare-bones package. Another fun Twitter search: “I wish Criterion would.” As you might imagine, there are hundreds of such tweets. Cinephiles are an obsessive lot. We get excited about movies and in the process we become advocates. The more inaccessible or overlooked the film, the more ardent we become. We want others to share our excitement, but access is paramount, and nothing assures excitement around a film quite like a Criterion release. As Joe Rubin, co-founder of cult DVD label Vinegar Syndrome, puts it: “Every Criterion film is an event.”

One consistent request on Twitter from female film critics and cinephiles in particular is more female-directed films. Last month, film critic Sophie Mayer analyzed Criterion’s entire collection and found that only 21 of their titles were directed or co-directed by women (including films released under Criterion’s Eclipse banner). That’s 2.6% of the whole collection, which in Mayer’s estimation is a “pretty meagre number.”

As telling as that number might be about a potential gender bias, the statistic only scratches the surface of what is a much broader and more complicated picture when it comes to releasing female-directed films on home video. It’s worth pointing out other characteristics of Criterion’s collection in relation to that figure. While Mayer notes a higher number of films are directed by women in mainstream film—a still-measly 7%—Criterion’s titles represent a diverse number of cinemas that do not fall necessarily in the mainstream category; it would likely be impossible to determine the percentage of women directors in every national cinema around the world since the birth of movies. That number is likely to be much lower than 7%.

The 2.6% number also doesn’t account for the decades when there were few working women directors around the world. While women directed movies in the early Hollywood era, the profession became mostly male territory by the 1930s, and for several subsequent decades, there were almost no female directors working at all in the studio system (with some notable exceptions, like Ida Lupino). Even by the 1960s, some of the world cinemas we cherish today were only starting to find their roots and hadn’t yet standardized the practice, or even implicitly decided to allow, encourage, or prohibit women to helm a picture. There were also more notable films made by women in the 1930s-1960s in other types of cinema—like avant-garde, independent, and documentary films—than in Hollywood. This hasn’t changed that much in the last half-century, as the gender bias in Hollywood continues to be a systemic problem. Even so, think of your favorite female-directed films: no matter which genre or country they hail from, the largest percentage were likely made in the 1970s or later. Despite the continuing gender bias, more women have been making movies of note in the last 30 to 40 years than in the decades preceding. This is an important factor to consider, as more than half of Criterion’s collection are films that were made in the 1930s-’70s. Much of their library derives from a period when there were generally fewer working female filmmakers.

Instead of relying on statistics to examine Criterion’s collection, then, it may be more helpful to think of women-directed titles that deserve a deluxe treatment. No matter what the numbers, statistics, or decades show, given their power, Criterion would go a long way in challenging the canon by releasing more titles made by women. But the reality is that releasing films from a smaller demographic is much more difficult than one might imagine.

Last week, I queried Twitter for female-directed titles that should get the Criterion treatment. Great responses poured in, among them the films of Dorothy Arzner and Maya Deren, Claire Denis’s Beau Travail, Barbara Loden’s Wanda, and Jennie Livingston’s Paris is Burning. Some of these films, however, are already available from other distributors, some with restorations and supplements that are on par with or close to the quality associated with Criterion.

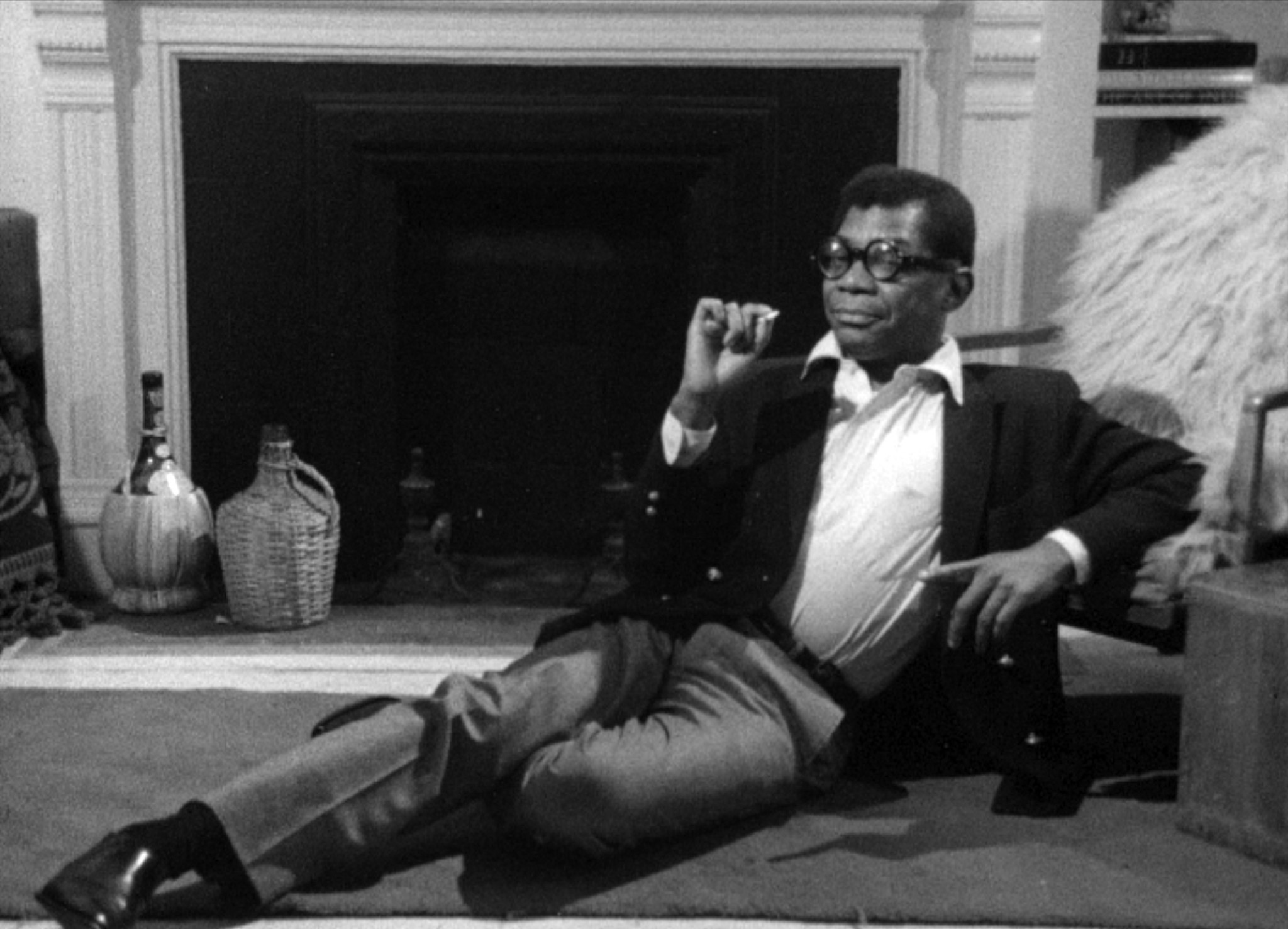

Milestone Films, for instance, has put out three of Shirley Clarke’s films: The Connection, Portrait of Jason, and Ornette: Made in America; another box set of shorts is on the way. “I think we’ve put Clarke back on the map,” Amy Heller, co-owner of Milestone, says. “It’s been very hard work. We had to restore them ourselves.”

Heller and her husband, Dennis Doros, run Milestone out of their own house. Keeping the operation small has allowed them to find, restore, and release films that would otherwise never see the light of day. They’ve been doing so for 26 years.

The way Heller puts it, at Milestone, they want to “fuck with the canon.” Many of their releases are by marginalized filmmakers or tackle subject matter less represented in cinema at large. Alongside Clarke’s films, they’ve put out gems like Kent Mackenzie’s The Exiles and Jane Campion’s debut film Two Friends.

Their catalog is fun to look at, but like any company of Milestone’s ilk, the titles don’t reveal the breadth of work that goes into each release. Putting out a dream title is not as simple as posting on Facebook or tweeting a favorite. It can take years, even decades, before a distributor has everything in place. Some issues these companies commonly encounter relate to licensing rights, obtaining access to full prints, and financing or finding a co-financier for a restoration.

“Dennis spent years finding the materials for Portrait of Jason,” Heller explains. They didn’t expect such a challenge initially, but when the materials from the Museum of Modern Art weren’t up to par, Heller recalls telling Doros, “‘Clarke’s a New York filmmaker, I bet you can find her materials.’ Famous last words!”

For Milestone’s release of Anthony Howarth’s 1976 documentary People of the Wind, the couple needed to track down a single person who owned the rights, but because of her generic name—Elizabeth Rogers—Milestone simply couldn’t find her. “We looked for her for 15 years,” Heller says. “We’d call people in the phone book and ask, ‘Are you the Elizabeth Rogers?’ ‘No.’” Eventually, Dennis had the idea of trying to find her father’s company’s lawyer, which finally directed them to the right Elizabeth Rogers, who had no problem licensing the film.

Sometimes the rights belong to a company, not an individual, but that doesn’t make them any easier to find, because companies can vanish as well. Other rights owners may be difficult to work with or demand too much money. Each film has a different set of circumstances surrounding its release—and a different set of problems. Studio licensing is a common roadblock for certain distributors specializing in classic Hollywood. While a company like Criterion has been able to sub-license classic films from Hollywood studios and give them the deluxe treatment, there are still hundreds more collecting dust in vaults because they’re unavailable to other distributors. Twilight Time is one such distributor: While they’ve made deals with certain studios, they’re locked out of others. “If I had a wish list, I guarantee there would be 30 films from Warner Brothers,” says Julie Kirgo, the creative director and essayist at Twilight Time. “But why won’t they license the films to us if they’re not putting them out themselves?”

Even Criterion has had trouble getting rights from certain studios—until recently. “Warner Brothers is finally thawing,” says Craig Keller, the ex-producer of the Masters of Cinema home-video line. “They were the last hold-out studio that didn’t want to license their ‘product’ away. They expect a certain return on investment, so it isn’t worth their time to only make a profit of say, $5 million.”

For a while, Warner refused to sub-license and instead took the cheapest shortcut in releasing films: they threw a bunch of titles on VOD platforms without doing any restoration work on them. This is why sub-licensing is so important. If you give DVD distributors a chance to beautify a beloved classic, everyone benefits: the studio, the DVD distributor, and cinephiles alike.

Another potential deal-breaker is a distributor’s ability to obtain a complete and workable print of the film. For Rubin, access can be difficult, given that Vinegar Syndrome specializes in exploitation, sexploitation, and hardcore films, which can be harder to find than your average studio title. This includes the work of female directors, who for the most part were few and far between in the genres and decades Vinegar Syndrome specializes in. There are barely a handful of names—Stephanie Rothman, Barbara Peeters and Roberta Findlay among them—so finding full prints of rare films made by even rarer filmmakers can be a challenge.

“Stephanie Rothman’s films are an interesting case study,” Rubin offers. While Rubin had bought the rights for three of Rothman’s films, he only had the negative for one of them. But by coincidence, Rubin met Rothman through a mutual friend who was trying to help her track down the rights owners to her films. “She was really keen to get her films restored,” Rubin explains. Rothman had managed to find the prints for the other two missing films, and they’re now collaborating together for the releases. In Rubin’s words, “these sorts of things tend to work very serendipitously.”

Considering these frustrations, the fact that DVDs of such films come out at all is sometimes a small miracle. Distributors advocate for little-known films that may also be possibly unprofitable. If they didn’t have a passion for cinema in spades, they simply wouldn’t have gotten into such a thankless business.

Rubin sees this passion evident among his boutique-label contemporaries. “Bill Lustig, who runs Blue Underground, once told me his philosophy for buying films,” Rubin says. “He wants to feel like every single film he puts out is a movie that could be someone’s favorite movie ever. He likes the idea that there’s someone out there who’s going to buy [it] and say, ‘Finally someone put out this movie that I’ve just loved my whole film-watching life, and I’m so excited about it.’”

![0 R UMAX PL-II V1.5 [3]](http://moviemezzanine.com/wp-content/uploads/Achmed.0.jpg)

Given that the business already has a small, niche consumer base, it becomes even trickier predicting what the niches within the niches might buy. Over the years, Heller has noticed that films made by women have definitely resulted in less-than-enthusiastic reactions. When Milestone puts out a film by a woman, “we’re definitely swimming upstream,” she says.

“Misogyny is not limited to production or distribution,” Heller explains. “But let me tell you, if you want to find a film that won’t make money, you should go after a film made by a woman. People won’t book them. People won’t buy them.”

Consumer demographics are important to consider here. The vast majority of people obsessively discussing home-video releases on the Internet are men. “These forums and websites are mostly dedicated to technical stuff like image quality,” says Alvaro García, a cinephile and home-video enthusiast who frequents sites like criterionforum.org and the DVDBeaver Facebook page, “which means they’re predominantly male groups for whom the lack of attention to female directors isn’t really a concern in their mind.”

One exception within this gendered demographic is the educational market, something that Kino Lorber, one of the larger distributors, has successfully latched onto.

“Women’s cinema is a large field of study in academia,” says Bret Wood, a producer at Kino Lorber. “It’s an interest among filmmakers and people who like cinema. It’s something we’re aware of and historically want to represent, but we also feel like we shouldn’t pat ourselves on the back or reduce the films for their accomplishment to simply the fact that they were made by women.”

That said, Wood points out that in addition to releasing women-directed films, Kino has occasionally put out themed collections that highlight a group of marginalized filmmakers, like a three-film box-set of early women directors, or a five-disc box-set of pioneering African-American filmmakers. These collections allow Wood to release multiple rare gems—features, shorts, and even fragments of film—that would otherwise never be released on their own on home video.

“I can curate things that are otherwise never going to get seen,” Wood says.

It’s one thing to give customers what they want, but another to create demand for something they don’t know they want. Which takes us back to the matter of canon. Why do film critics care how many films Criterion is releasing made by women, instead of by large companies like Kino, or small niche labels like Vinegar Syndrome?

While the collection has many blind spots, Criterion’s roster is diverse enough to offer cinephiles a definitive taste from all around the world, from each genre and decade. By offering a little bit of everything, it can more easily present itself as a definitive canon. The level of prestige Criterion carries is so high that it can easily challenge the male-dominated film canon as we know it, exposing a much larger number of cinephiles to female-directed films.

“Criterion is certainly very well funded,” says Rubin. “One of the biggest things they have going for them, beyond their very careful marketing, which they’ve been very good at from day one, is that they’ve been around for a long time.”

In addition to their longevity, Criterion has long held the rights to a large library courtesy of Janus Films—the home-video equivalent of getting the coveted titular leads from Glengarry Glen Ross. You couldn’t quite call such an asset a head start; it’s more like finishing the race before your competitors have even had a chance to begin.

“They were one of the first companies to really get into DVD,” adds Rubin. “They’ve been really smart about technology, and they always knew how to price themselves into a special boutique area.”

In addition to demanding high-quality restorations, Criterion also came to distinguish themselves by creating a demand for elaborate special features, including well-articulated and intelligent essays, commentaries, interviews and documentaries, many of them produced in-house. Most DVD distributors can’t top that. While many companies, Criterion included, will restore at least some of their films through the assistance of other organizations, Criterion will always have more money to finish a top-notch restoration than most other DVD labels. Creating special features can also be expensive, so for many labels it boils down to budget. What’s more important: making a beautiful transfer, buying rights for more films, or creating bonus features?

Rubin says he includes special features on Vinegar Syndrome films if they’re readily available, which, given the rarified status of his films, is not always the case. “Which is not to say we don’t have them; we always do on Blu-rays,” he clarifies. “We always try to get an interview or commentary that is relevant and will heighten the intellectual experience of watching the film. But it’s not our number-one priority.” With the budgets he’s working with, it can’t be.

In order to even have a fighting chance of competing with Criterion, restoration is top priority for most companies, though sometimes it’s not always feasible to properly restore a film. In that case, a company may instead decide to invest funds into a plethora of special features to satisfy a customer, since they know that no matter how much money the company dumps into trying to restore something, it can never be perfect.

“Booklets are the number-one thing we’re known for,” Keller says of Masters of Cinema. In addition to commissioning essays, Keller was known for translating French criticism to be included in the Masters of Cinema booklets, including materials from Cahiers du Cinéma. “I wanted these texts available to an anglophone audience,” he explains.

At Milestone, the company’s passion for history is reflected in their commitment to preserving a film’s legacy—which is not something most DVD companies even think about. “We output to 35mm and we make sure it ends up in an archive,” Heller says. “We’re very history-minded.”

Heller sees each Milestone title as possibly having its first, only, and/or last-ever possible release on home video. This helps guide the couple in determining what special features should go on the disc. They research and help create materials that will provide the viewer with as much cultural, historical, and political context that’s needed to truly appreciate a Milestone movie. “Because who knows if anyone will ever do this again!” Heller says.

There’s no doubt that releasing films by women will perhaps start to change the minds of the heavily male consumer base who don’t think about women’s cinema because a reputable organization like Criterion hasn’t championed them. But the more you learn about the hard work that other DVD distributors put into their own releases, the more you want to challenge cinephiles’ perceptions of Criterion as the unquestioned head of the pack. When a film comes out on another label, featuring a beautifully restored transfer and enlightening special features, is all that’s missing from the “perfect” cinephile experience a spine number and some clever cover art?

“Criterion’s been able to build this reputation as the gold standard,” says Robert Sweeney, another Kino Lorber producer. “That can be frustrating because lots of companies are putting out great material that don’t always elicit the same response.”

“There are a lot of us making films that don’t always get on the pop-culture radar,” says Wood. “People think Criterion is the be-all and end-all of classic film. But if people really care about finding these films, they need to look a little wider. And you’d be surprised at what is actually out there.”

Both Wood and Sweeney told me that they highly respected Criterion, and I heard virtually the same line from every distributor I talked to. “We here at Twilight Time look up to Criterion,” says Kirgo. “It’s a tiny world and if you can get along with your rival, it’s a good thing. Everyone’s doing something a little different.”

But by continuing to put Criterion on such a high pedestal, perhaps we’re all doing ourselves—and the advocacy of marginalized filmmakers—more harm than we realize. To be sure, Criterion is the best in the business, and still worth celebrating. But it’s also time we got off the beaten path and consider films distributed on home video by other companies, labels run by passionate people who love the same films and directors we do. We live in an age where virtually everything is available to us at our fingertips. If we want to be advocates for women-directed films, it’s also in our best interest to, as Heller said, “fuck with the canon,” and simultaneously promote the amazing restoration work of these underdog labels, who not only love these marginalized movies, but work so hard to get them out.

Some companies that have released movies made and written by women:

- Milestone Films has released, among others, A Shirley Clarke collection, Jane Campion’s Two Friends, Lotte Reiniger’s The Adventures of Prince Achmed, and Margot Benacerraf’s Araya.

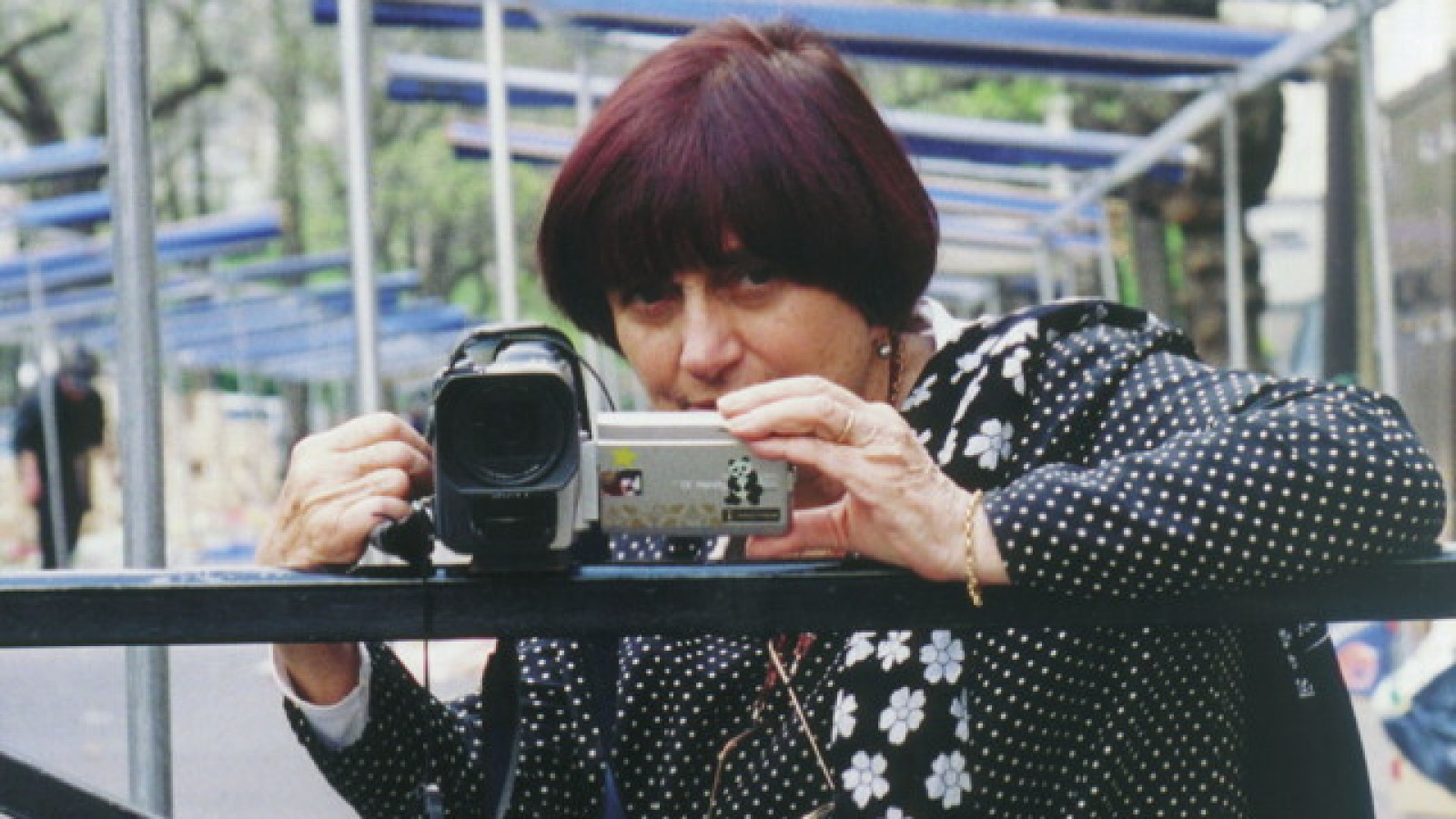

- Zeitgeist films has almost 50 films directed by women in a 130-title catalogue, including Agnès Varda’s The Gleaners and I and Talya Lavie’s Zero Motivation.

- Kino Lorber carries a number of female-directed films as diverse as Ida Lupino’s The Hitch-Hiker, Ana Lily Amirpour’s A Girl Who Walks Home Alone At Night, and an upcoming Lois Weber collection.

- Twilight Time has released multiple films written and/or directed by women including Nora Ephron’s Sleepless in Seattle and Barbra Streisand’s Yentl.

Editor’s note. In the process of researching, reporting, and writing this piece, Tina Hassannia reached out to the Criterion Collection for a response regarding its catalog titles written and/or directed by women. Peter Becker, president of the Criterion Collection, responded in detail; we have included his response as a separate post, and thank him for his honest and thorough comments.

14 thoughts on “No Home Video: On Women-Directed Films”

Pingback: A Response From Criterion | Movie Mezzanine

I do love Criterion very much, but I also agree whole heartedly with Wood and Sweeney. There are so many other folks doing great work. The Criterion Facebook page is littered with posts by people looking for films to be put out by Criterion that already have great editions out in the market. The idea that they wouldn’t buy it unless Criterion puts it out is crazy.

This article says so much that needed to be said – particularly about the smaller distributors. Though I have to say, I don’t think that the idea should be to release women-directed films as a way to get MEN to care more about them, but releasing women-directed films should be about getting WOMEN to realize that cinema might be an artistic medium that can inspire, touch, and speak to them, which I don’t think women feel now.

The assumption that men are genetically more outspoken in speaking out for niche films – which I can believe may be true to some degree – infers the idea that it is THEY who should be converted to women’s films, when really I think that women have so little access to cinema that touches them that they do not know WHAT films they could promote.

Pingback: Tina Hassania Says Small Video Labels Aren’t Distributing Enough Films Directed By Women… But It’s Complicated « Movie City News

There are a LOT of films directed by women that have been released by Criterion. There is a box of Chantal Akerman’s work, along with her magnum opus Jeanne Dielman, There are two box sets by Agnes Varda, films by Claire Denis, Lena Dunham’s debut film, 2 films by Jane Campion, Lynne Ramsay’s Ratcatcher.

Perhaps the writer of this piece should do some research first before trashing one of the finest DVD/Bluray companies in the world.

Don’t forget the Larisa Shepitko box set from Criterion (well worth checking out).

The Ascent is a masterpiece.

I forgot about that when mentioning female directors not highlighted in the comments section of the Becker response. A great set!

Maybe you should do your research? Even with all those women directors you mentioned, it only totals 21 films in the entire Criterion Collection directed by women. The writer said as much in the piece.

“Last month, film critic Sophie Mayer analyzed Criterion’s entire collection and found that only 21 of their titles were directed or co-directed by women (including films released under Criterion’s Eclipse banner). That’s 2.6% of the whole collection, which in Mayer’s estimation is a “pretty meagre number.”

21. That’s all, even counting all the ones you mentioned by Akerman, Varda, Denis, Dunham, Campion, and Ramsay.

Pingback: UNL | Frame by Frame | Tina Hassannia – No DVDs of Many Films by Women Directors

Pingback: This Week’s Good Reads (Week of March 28) | SAGindie

Pingback: The View Beyond Parallax… more reads for the week of April 8 - Parallax View

Hey, thanks Tina for the wonderful essay! I really enjoyed talking with you about films, women, and distribution — topics close to my heart as I have spent the last 30 years working and thinking about these issues.

I did want to clarify something. While the process of researching, locating and restoring the Shirley Clarke film WAS a lot of hard work, we could not have done it without partnering with four great film archives. For Ornette: Made in America, we brought the original elements to Ross Lipman at the UCLA Film & Television Archive and then worked together with cinematographer Ed Lachmann to digitally master the complex mix of audio and multiple film/video formats. Finally FotoKem created 35mm master materials and print.

For Portrait of Jason, my husband and partner Dennis Doros searched for several years to locate and identify the missing film at the Wisconsin Center for Theater and Film. Then, as the 16mm fine grain was slightly re-edited before the film was blown up, he also found an excellent 35mm print at the Swedish Film Institute — which archivist Jon Wengström generously lent us. We brought these disparate materials to Joe Lindner and Mike Pogorzelski at the Academy Film Archive (part of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences) and they worked with Modern VideoFilm to match and digitize the film, and finally to output to 35mm.

These details may seems a bit specific and wonky, but truly without the world’s great film archives, very few independent films would ever get restored. Here at Milestone, we have done independent restorations of a couple of films (including two by women, Margot Benacerraf’s Araya and Jane Campion’s Two Friends), and we are grateful for the chance to work with passionate, dedicated and meticulous professional archivists.

Pingback: The Future of Movie Mezzanine | Movie Mezzanine