There Will Be Blood (2007)

For those who thrilled to the bold style and virtuosic camerawork of Paul Thomas Anderson’s early films—most notably, the massive Altman-esque ensemble epics Boogie Nights and Magnolia, and the somber and eccentrically manic romantic comedy Punch-Drunk Love—the unadorned austerity of There Will Be Blood must have come as a shock. No ensemble cast, no kinetic cinematography, the camera slowly winding through craggy environments like oil slowly winding through hardened earth, Anderson’s usually diverse color palette usurped by blacks, browns, and fiery oranges. That is not to say, however, that Anderson has abandoned his usual themes: meditations on fame, suffering, and broken love. Instead, he raises them to a cosmically primitive level. It’s a cinematic scowl, the inverse of Anderson’s previous work, yet still very much his own.

Daniel Day-Lewis is the eruptive Daniel Plainview, a miner-turned-oil tycoon, making millions by using his silver tongue and adopted son to convince towns to drill for oil. Eventually, he is invited to the Sunday Ranch in California where he clashes with Eli Sunday (Paul Dano), the local preacher and wolf in sheep’s clothing who desires money to construct his church. These men battle for their respective kingdoms of oil and religion.

Cinematographer Robert Elswit shoots gorgeous wide-angle shots of the West and employs slowly tracking cameras which weave around men and their machinations. The structures of men are imposed upon those of the earth, and as great peaks are gazed upon, Johnny Greenwood’s unhinged atonal score shakes loose typical feelings of glory and pride. Anderson, in essence, is playing God, burying these men in the American hills in immortalization not judgment.

It’s the American dream as human devolution, a splitting-open of American opportunism revealing a decimated core. Anderson dares to compete with the likes of Citizen Kane and The Treasure of the Sierra Madre, and damned if he doesn’t back up that ambition by coming up with a masterpiece of his own. – Colin Stacy

The Master (2012)

The Master almost feels like Paul Thomas Anderson’s statement of intent in response to the popular approval of his previous film. Here was an independent filmmaker who’d suddenly broken through to Oscar voters in a big way—eight nominations and two wins for There Will Be Blood—and he followed that up, five years later, with something indulgent, less crowd-pleasing, and more slippery than anything else he’d done. The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, which granted the film three obviously deserved acting nominations, didn’t appear to know what else to do with The Master. Not that it mattered: A little woozier in its style, freer in its arrangement, and a lot more idiosyncratic than Anderson’s prior efforts, The Master is the first film of Anderson’s that truly feels like his own, without meriting comparisons to obvious forebears like Martin Scorsese, Robert Altman or Stanley Kubrick.

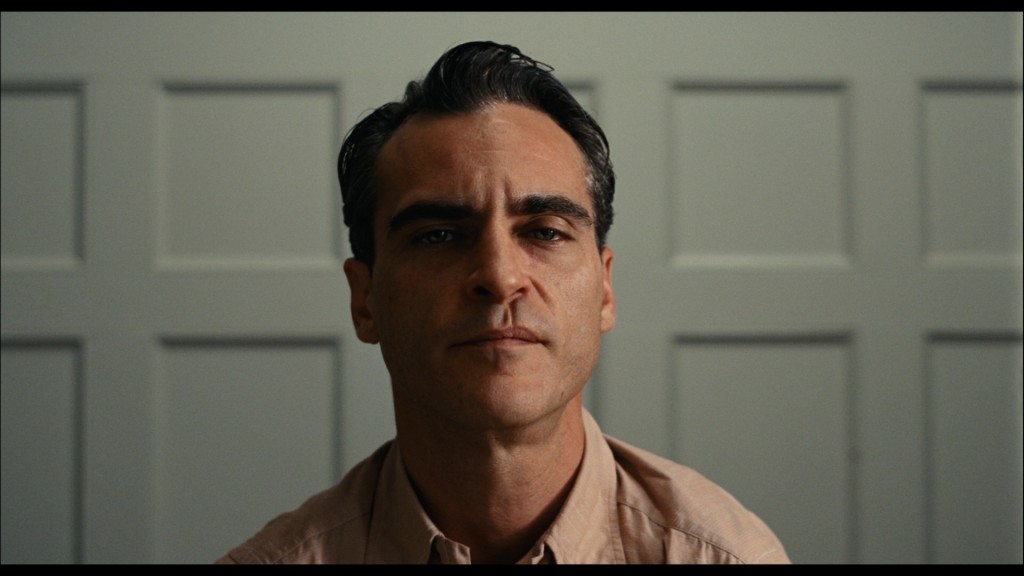

Retelling the L. Ron Hubbard origin story as a way of exploring American masculinity after World War II, The Master spoils its audience with rich photography from Mihai Malaimare Jr. (replacing regular Anderson DP Robert Elswit), a dreamy Jonny Greenwood score, and two dueling lead performances that infuse Anderson’s fifth feature with a jolt of darkly comic energy. As wrecked alcoholic drifter Freddie Quell and Hubbard-like cult leader Lancaster Dodd, two opposing forces sharing a bond through some strange alchemy, Joaquin Phoenix and Philip Seymour Hoffman have never individually found a better match nor, arguably, given better performances. Quell and Dodd’s warily loving connection forms the basis for another of Anderson’s troubled surrogate father-and-son relationships, and provides Anderson with an emotionally unstable core for this, his most nakedly affecting film. Some find The Master over-long (they’re right), while others think it a spellbinding masterpiece (they’re also right). For Anderson, it’s an evolutionary leap towards a unique cinematic style. – Brogan Morris

Inherent Vice (2014)

What if Paul Thomas Anderson wasn’t the much-cherished heir apparent to American Cinema that many in certain circles wish him to be? What if the dude just wanted to get baked for two hours and imagine Cornelius the Ape tripping on acid to Can while starring in a Pink Panther movie? Anderson’s new film Inherent Vice, which is neither a masterpiece nor anything that aspires to such, supports the theory that he’s always been first and foremost a great director of comedy. Despite the ambition associated with his recent work—their formal grandeur, volcanic performances and evocation of American history—it’s easy to overlook that films like There Will Be Blood and The Master were more often than not hysterically funny in their parodies of the human animal. Vice confirms Anderson as a bona fide satirist.

In adapting Thomas Pynchon’s rambling, drug-fried gumshoe novel set in 1970 Los Angeles, Anderson has returned to the funkier ensemble rhythms of his breakthrough, Boogie Nights, but wrapped them in the audacious style of The Master. The fusion of Pynchon’s antic dialogue and Anderson’s wandering camera can be jarring, but when the chemistry works—witness the slow, creeping pushes in toward unknowing characters in conversation—the result is a wonderful slipstream of madness. Read full review here. – Luke Goodsell