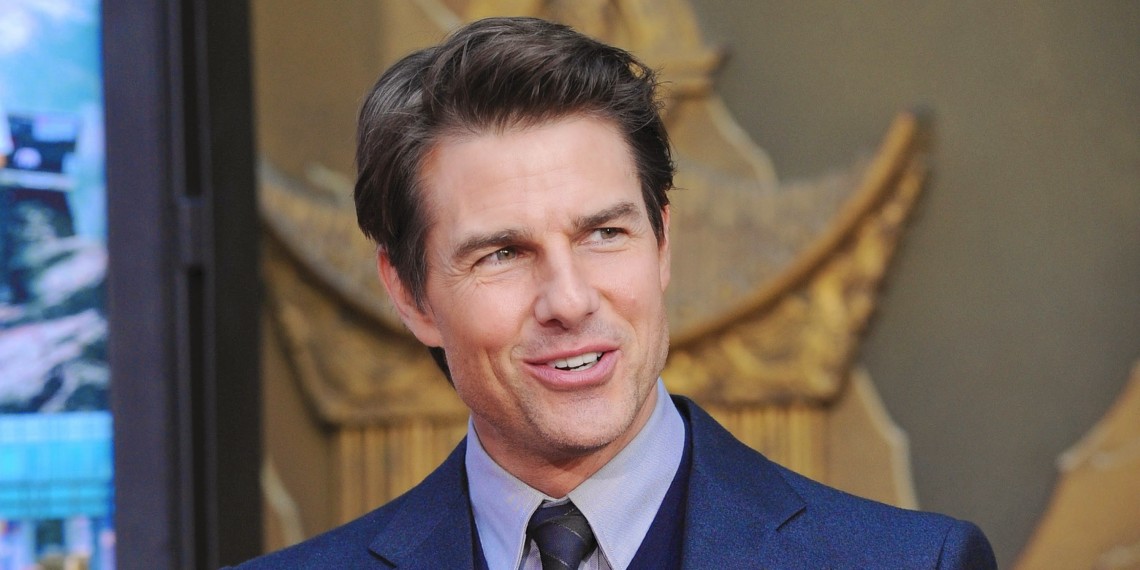

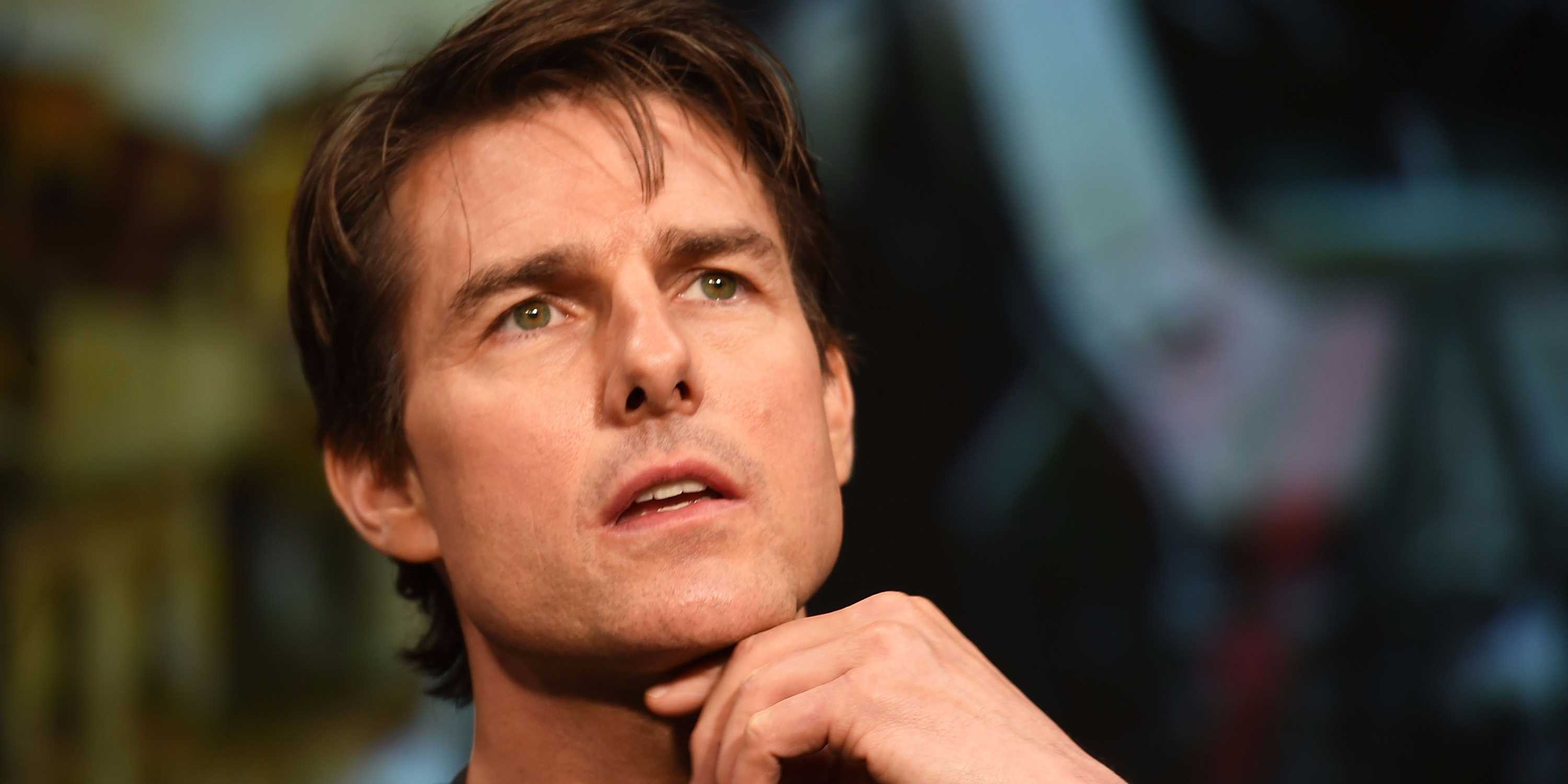

Tom Cruise imbues every performance with an exciting amount of personality and charisma. There is no one more fun to watch onscreen on a consistent basis. Yet the world remembers: He still jumped on Oprah’s couch.

Despite a prolific career, years of apologizing and efforts in image reversal, the couch jump may be Cruise’s most eternal role. It’s become even difficult for a fan to express an appreciation for Tom Cruise without some sort of explanation. “Well, I like his movies, not him as a person.” “Well, he’s nuts, but he’s a good actor.” “Well, he has crazy religious beliefs, but he’s fun to watch.” Tom Cruise is a singular celebrity, yet he represents our larger celebrity culture which cannot come to terms with how to separate art from artists, or whether we should, when we should, or if we even can.

Whatever the case, Cruise should be thankful that the incident happened 10 years ago and not today. That event, along with more outright meltdowns by celebrities, has helped to further propel our culture to one of hyper-attentive consumption and dissection, aided by the ubiquity and instantaneousness of social media. It’s become formulaic: We build them up, watch them fall, and wait for the comeback. It would be worth arguing that Cruise’s moments of perceived craziness have impacted our culture more than they’ve impacted him. We remember the couch, oh we always will, but he’s still opening giant action movies. He’s fine. But celebrity culture has undergone a massive shift in the decade since (this is mostly a case of correlation, not causation), and remains in acceleration.

It stands to reason that the more we know about an actor’s personal life, the harder it is to separate that from their characters. This has certainly manifested in Cruise’s roles over the last decade. Since the beginning of his career, Cruise has made very deliberate career choices. One of the first he took on after Oprah, after the third Mission: Impossible film, was Les Grossman in Tropic Thunder. This was an obvious attempt to improve his image by playing a character unlike the ones he normally plays, and by satirizing his own persona. His performance as Stacee Jaxx in Rock of Ages in 2012 was a similar effort.

Beyond these two roles, Cruise has stuck mostly to action films, including two additional Mission: Impossible movies — a dependable franchise — and last year’s inventive sci-fi Edge of Tomorrow. He brings an element of emotion in these films, but only inasmuch as an action film ever needs it. Exceptions to the genre movies are rare; Lions for Lambs and Valkyrie were financial failures. In other words, Cruise has avoided the kind of “serious” roles that helped establish him in his younger years, from Jerry Maguire to Rain Man to A Few Good Men. His comedic and action roles in recent years do not require the audience to make a particular emotional connection with his characters, something he has not asked of us since the chaos that unfolded around his real-life behavior. This can’t help but feel like a conscious decision on the actor’s part. Cruise has spent a decade atoning for his strange behavior, choosing movies that will remain palatable for moviegoers. There’s something dissatisfying about that.

But it’s an issue that is becoming–or has become–an all-encompassing one for the industry. We learn the intimate details of these people’s lives, with or without their consent, and every character they play is inevitably informed by those details. Some movies are more capable than others at making us forget what or who we’re watching, some movies solve the problem by using lesser-known or unknown actors, and some movies make an effort to make meta commentary out of their performers. For example, one of the best performances of the year is Kristen Stewart’s in Clouds of Sils Maria, a role in which she often acts as commentary on her real-life, Twilight-infused, tabloid-heavy persona. This is also what Cruise has done, to a degree, in Tropic Thunder and Rock of Ages. If that is the reality of the film industry today, our biggest stars seem to be thinking, it might be best to embrace it and wink back at the audience.

This inevitably causes trouble in the casting process, perhaps choosing actors based on their notoriety or lack thereof. More importantly, though, it becomes much more difficult for a storyteller to tell the tale they want to if they have to account for what preconceptions moviegoers will have of their actors, who remain actors without becoming characters. This is not a new phenomenon, as film has always grappled with whether it can properly immerse people in its worlds. But it is harder than ever to separate the knowledge we have about performers from the characters they play. Tom Cruise is such an intensely likable guy, but his art is clouded by his antics for love and his religious beliefs.

I haven’t watched a Woody Allen movie since Dylan Farrow published her story, because it feels impossible to watch one without thinking about that (especially when his newest film is at least partially about a much younger woman pining after an older man in a position of power over her). I’m relatively certain that I won’t watch an episode of The Cosby Show in my life, missing out on one of television’s most legendary accomplishments. Truth be told, there is something altogether different about these cases, however. They hurt other people. They are either definitively monsters (in Cosby’s case) or are accused of such (in Allen’s).

When we have exhausting conversations about separating these artists from their art, when people ask me how I can eagerly watch Roman Polanski movies while shunning Allen’s films, when we argue about whose art is worth keeping in the canon despite their monstrous acts, we are having a different and much more complicated discussion than the one centred around Cruise and celebrities like him. For me, the legacy of the work these men have shared are irrelevant to the hurt they have caused. “Even considering Cosby’s legacy or what he meant to me or anyone else focuses the conversation on him and the possibility of redemption instead of where it belongs–the women he hurt, the hypocrisy, the culture that allowed his criminality to thrive,” Roxane Gay wrote earlier this week. “We must choose humanity over legacy and over art or accomplishment.”

You are not a monster if you watch The Cosby Show, or Irrational Man, or Rosemary’s Baby. But in these cases, ones where they have hurt real people in the real world, it does seem irresponsible to not carry that knowledge into the film or show with you, and to not mention it. The plague of silence around monstrous acts is only perpetuated if they remain unacknowledged.

On the other hand, Tom Cruise has not hurt anyone. There is no responsibility on us to keep his exploits in mind. The issue is whether it is possible. How can we allow filmmakers to tell the stories they want to tell if we cannot keep Oprah’s couch and L. Ron Hubbard from our minds? As often as I have become completely enveloped into a film’s story, forgetting about who I’m watching or who made it, I’m not convinced that this can always be overcome. As Ronald Bergan wrote in The Film Book, “Most actors still manage their careers effectively by remaining consistent to the sensibilities they have established in their films. So, Tom Hanks will doubtless continue to represent the decent everyman, while Julia Roberts is likely to remain the accessible, practical everywoman.” One can imagine that if it came out that Hanks had committed an awful act that ruined his reputation, he would be unable to convincingly play the decent everyman in future roles without the audience taking some umbrage. But Hanks generally lacks even any of the strangeness Cruise displays, so his persona remains undisturbed.

The old belief was that quality acting and quality material can beat the problem of “the movie star,” which may have been true at some point on its own, but it no longer seems entirely sustainable, and maybe it doesn’t have to be. We often go to films to experience someone else’s subjectivity, to embody the perspective of someone unlike ourselves and identify with them, and it is up to the actor to make this work. But when the actor’s persona takes precedence over their character, we may be forced to recalibrate our spectatorship accordingly. Maybe we just need to relearn how to have an aesthetic experience of cinema in an oversaturated culture as a coexistence of reality and fiction, as movies always have been, both actors on a soundstage and characters in Tokyo or Singapore or London. In other words: don’t let love and religion ruin Tom Cruise for you.

3 thoughts on “The Cult of Tom Cruise”

I’m a firm believer in separating the character from the man. Humans are multi-faceted creatures. Each of us has our demons, but those demons should never be seen as the sum of an individual. A great artist and a monster can inhabit the same body. I imagine there are plenty of artists who have done heinous things we will never be aware of. As a movie-goer, I’m only there to judge the film. The person playing the part is not the character and never will be. If I based my consumption of any product on the man behind it, I would probably never purchase anything.

This is the best comment I’ve read, regarding this topic. Thank you.

I’d say it’s probably a bit more complicated than that, but it’s funny where we draw the line. How we decide THIS is okay but THIS isn’t and how we try so desperately to preach to others to fall in line with our thinking. I agree on most accounts, I think Roman Polanski did some horrible things but it will never stop me from watching his films, for example. There are certain people though that are so obnoxious or horrible its hard to ignore it if you know enough about them, it’s tough to not read into their work as reflections of their worldview, etc. especially if they are deliberately doing so (Frank Miller for example). That said, it’s up to each person to draw that line for themselves, just please, don’t try to patronize everyone else.