Several years after putting production work “on hiatus,” internationally beloved Japanese animation house Studio Ghibli is back… in a way. The Red Turtle, a co-production of the studio, hits theaters this weekend. Though created mainly by a team of Europeans, headed by Dutch director Michaël Dudok de Wit and animated by French company Prima Linea, the movie bears veteran Ghibli execs Toshio Suzuki and Isao Takahata as producers. It comes with their plaudits as well. But that seems a tenuous basis upon which to declare The Red Turtle “the new Studio Ghibli film.” Setting behind-the-scenes details aside, I think it’d be even more of a mistake to try to approach the movie as a Ghibli work on an aesthetic basis.

It’s not difficult for a Western animated film to snag a comparison to the Ghibli oeuvre. Anything that seems to break the mold of the cynical big-studio cartoons seems like a breath of fresh air – especially anything that strives to bring the audience some striking imagery. That’s how starved the Western audience is for animation that doesn’t feel like it exists to sell merchandise before anything else. And pretty much any powerful animation figure one can name, from John Lasseter to Laika’s Travis Knight, will eagerly name-check Ghibli in general and Hayao Miyazaki in particular as role models. Despite this, I can rarely detect direct Ghibli fingerprints on any work not made by the studio itself. This isn’t necessarily bad. As long as we have the studio, why would we need anyone else to produce similar stuff? But it’s worth defining precisely what Ghibli does so well, so singularly, and what other animators lose in the attempt at imitation. After all, with the studio’s future still somewhat ambiguous, who knows how much longer we’ll be getting new work from it?

Even if The Red Turtle didn’t have the Studio Ghibli logo in its opening credits, at least a few critics would probably call it Ghibli-esque. There are elements that superficially could be said to be in the spirit of the studio. It’s quiet (silent, in fact), a rarity for Western animated features. It’s leisurely paced. It’s immersed in the natural world. It definitely isn’t commercial. It has philosophical matters on its mind. This is all certainly enough to separate it from mainstream feature animation, but is that automatically “like Ghibli” simply because many Ghibli films share such traits? I’d argue no, because the way in which The Red Turtle expresses these qualities is different from how Ghibli films typically do so.

This, on its own, doesn’t make The Red Turtle inferior to Ghibli’s works (though I’d sooner rewatch almost any Ghibli movie first). It’s just different. My point is that the mainline criticism of animation is so bereft that it can only express appreciation in frustratingly broad terms. “Studio Ghibli” has become critical shorthand for “artistic animation,” which misses reams of nuance and can’t articulate what actually sets the studio’s filmmaking philosophy apart from any others’. This in turn speaks to a broader difficulty American criticism has approaching animation as an art form. To an extent, this makes sense in that the medium has historically been viewed primarily as a vector for children’s entertainment and thus easy to dismiss (even if that’s a wrongheaded instinct for approaching children’s entertainment). We should do this no longer.

Broadly, the Ghibli style can be described in terms of art, character expression, and tone. A more in-depth explication is possible, but is perhaps better saved for a longer feature specifically about the studio’s body of work. Here, we’ll stick to those three “pillars,” examining each in turn.

First is the art, the basic consideration animators give to how they depict their worlds. Directors like Takahata, Miyazaki, and the late Yoshifumi Kondō express this through vivid, lived-in particulars. The studio’s in-house style revolves around creating environments that are extraordinarily detailed in a paradoxically unshowy way. A good way to understand this is to compare it to Disney’s technically proficient computer animation, which has brought us intricate yet sterile worlds in such films as Zootopia, Moana, or Wreck-It Ralph. These are movies of visual overload, featuring constant moving subjects, backgrounds, and foregrounds working in dizzying concert (including a literal concert capping off Zootopia). There’s so much to take in—too much. Ghibli films have just as much background detail but never forget to center on character, thus letting those details enrich their sense of immersion. Compare the titular city of Zootopia to the bathhouse of Spirited Away—both colorful, otherworldly realms populated by a host of diverse species, but the latter is much more memorable and interesting to look at.

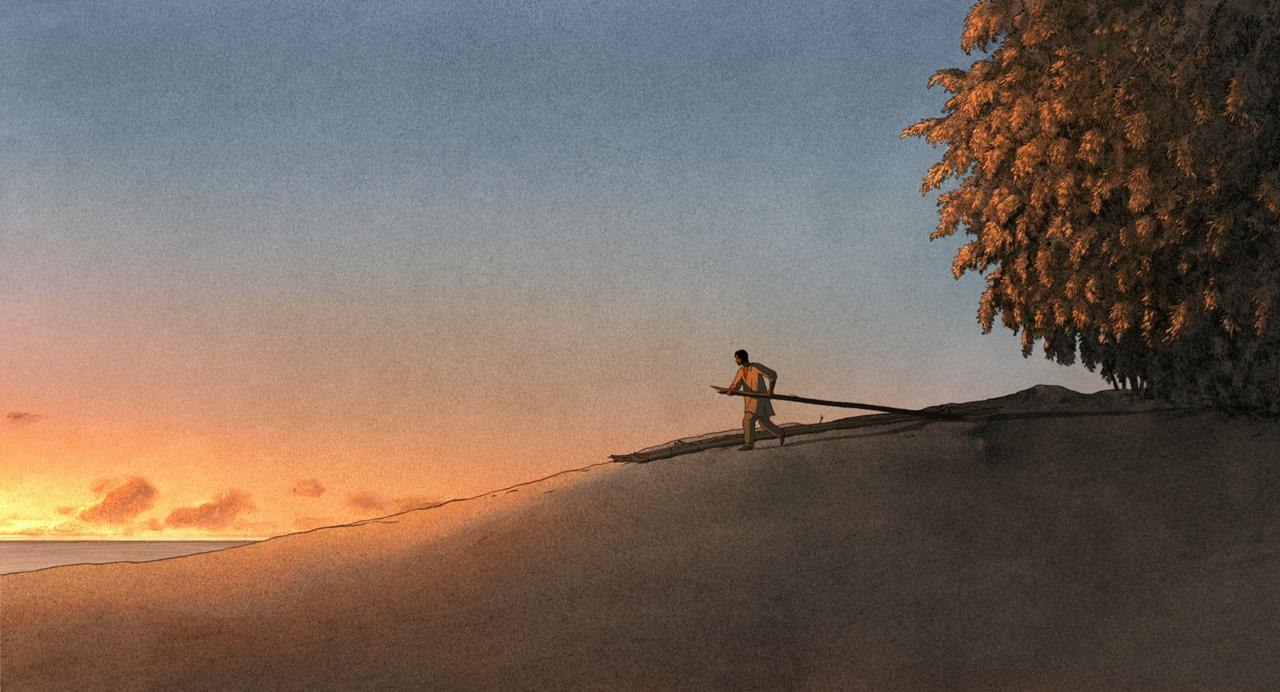

The Red Turtle features exquisitely rendered jungle vistas on its island setting. It is frequently pleasant to look at. But it also does something that even the least of the Ghibli films have never done: it wears out its look’s welcome. In contrast to the rich palette favored by most Ghiblis, Red Turtle sticks mainly with earthen tones—dark-hued greens and browns and tans. Even the sun-dappled ocean looks muted. In this way, the eponymous turtle comes across as otherworldly, in a basic but effective use of color as storytelling. The aesthetic is fine initially, but becomes overly familiar in the movie’s 80-minute runtime. Most Ghibli films don’t let themselves go more than a few scenes without introducing something new to take in. Dudok de Wit has until now only directed shorts, which is not the only way in which this movie may have been better off with a trimmed breadth.

Ghibli’s characters act with studied deliberation, the animators paying special attention to body language, minor facial expressions, and gestures. As a link above explains, this has always been a hallmark of anime, which uses fewer frames per second than Western animation. It isn’t inherently superior to American character animation, which has its own rich visual vocabulary going back to the days of Walt Disney himself. But it’s difficult to imagine an American film taking time to focus on a character frying up breakfast the way Howl’s Moving Castle does. Hell, Ratatouille is all about cooking, and yet its brisk, action-oriented angle on the kitchen leaves few moments to convey the pleasure of the craft. The movie’s abstract expressionist depiction of how its main character experiences flavor can’t quite capture the sensation the way a sizzling Ghibli smorgasbord can.

The Red Turtle might appear to be totally about expression via character movement. After all, it is completely dialogue-free. But while Dudok de Wit is keyed into his main character’s gestures and actions, the character himself is a blank. This is by design—the plot is largely allegorical (though I’d trip a few times trying to explain precisely what the allegory is, specifically what it means when you murder a turtle and it turns into a woman for you). Again, this is not to dismiss the film out of hand. It’s fine that the lead is a symbol, less a man than “Man.” But that is not Ghibli-like in the least. Even minor Ghibli characters are granted a sense of individuality and interior lives. This personality works in concert with their animation, with the writing and action feeding into one another. Many in the Ghibli stable of artists are avowed humanists, and the way they treat the denizens of their worlds is a subtle manifestation of that.

Finally, there is tone, which is by far the hardest thing for anyone trying to be like Ghibli to duplicate. Kubo and the Two Strings couldn’t do it. The Avatar and Legend of Korra series tried many times and never quite managed it. The Red Turtle aims for something like it and misses. I refer not to a single Ghibli tone that exists to imitate, but to how Ghibli movies can, with no evident effort whatsoever, incorporate the mundane and the commonplace into even the most fantastical narratives. Think of the aforementioned cooking scene from Howl’s Moving Castle, or the iconic scene of the sisters waiting in the rain for a bus alongside a gargantuan creature in My Neighbor Totoro, or Chihiro and a cadre of spirit friends riding a magic train like everyday commuters in Spirited Away. These stories give themselves room to breathe. They let themselves slow down. They aren’t afraid of quiet. All of which is anathema to most major American animation studios. The only immediate counter-example that springs to mind is Adventure Time, which has spent many 11-minute segments forgoing “plot” to hang out with its characters.

The Red Turtle is slowly paced and free of dialogue, but that does not necessarily make it quiet. In fact, save a few grace notes, like a scene of a baby playing with crabs on a beach, it’s quite focused on the progression of its allegory—one action following another. Contradictorily for a film about existence, it does not give its characters many moments in which to simply exist, the way so many Ghibli films so often do. This is another reason the feature length wears on the viewer, disengaging when it could have provoked them.

There’s a basic reason why it’s difficult for mainstream Western animation to take the steps needed to truly imitate the Ghibli philosophy: money. While mid-budget studio films are all but extinct in the live-action realm, they were almost nonexistent before. An animated feature usually represents an investment of hundreds of millions of dollars and countless work hours. Disney, Pixar, DreamWorks, and the like rigorously focus-test and second-guess every artistic decision in the process. What studio is going to risk allowing aesthetic choices that kids might perceive as “boring” to slip through? No matter how much Lasseter et al may admire Miyazaki, they might simply not be allowed to try to be too much like him. Though the pretty-but-hollow Kubo and the Two Strings, for example, demonstrates that even artistic freedom might not guarantee that one capture Ghibli magic. And of course, that the Ghibli-supported Red Turtle doesn’t feel very Ghibli-like at all suggests that the studio may simply be inimitable. This is perhaps a greater testament to the prowess of those artists than any award or box office take.