If Italian maestro Paolo Sorrentino had chosen to begin his most recent film, the Academy Award winning The Great Beauty, with the picture’s extended introductory saturnalia, viewers might not have missed a beat; the movie’s very first scene almost feels like an unrelated vignette, a mini-narrative of its very own, rather than an integral part of the narrative. What do the Fontana dell’Acqua Paola, a tour group of Asian sightseers, a scenic view of Italy’s capital, and a sudden case of death have to do with the portrait of avarice, class boredom, and meaningless frivolity that Sorrentino crafts throughout the remaining span of The Great Beauty’s running time? Nothing, and yet everything.

The film opens at the aforementioned Roman landmark, a serenely timeworn piece of architecture situated atop the Janiculum hill. Janiculum doesn’t count among the city’s Seven Hills, each located within the heart of Italy’s capital and ensconced by the Servian wall; regardless of the snub, it affords a breathtaking sweep of Rome’s stunningly gorgeous antiquity. As everybody else in the aforementioned tour group snaps photos, one lone excursionist separates himself from the pack, gazes upon the vast expanse of Rome as it stretches before him, and takes in a deeply felt sigh of satisfaction. It’s a sight so beautiful, he could simply die.

So, of course, he promptly croaks on the spot, eliciting a scream which we at initiallty assume is emanating from a bystander. It turns out that the ear-raking sound we’re hearing is actually that of an elegantly attired partygoer at the unhinged soiree The Great Beauty almost immediately transitions into after the nameless deceased’s fatally wondrous encounter with Rome; it’s at this moment that the film truly begins, and we very nearly forget everything Sorrentino sought to convey to us in its tranquil preamble.

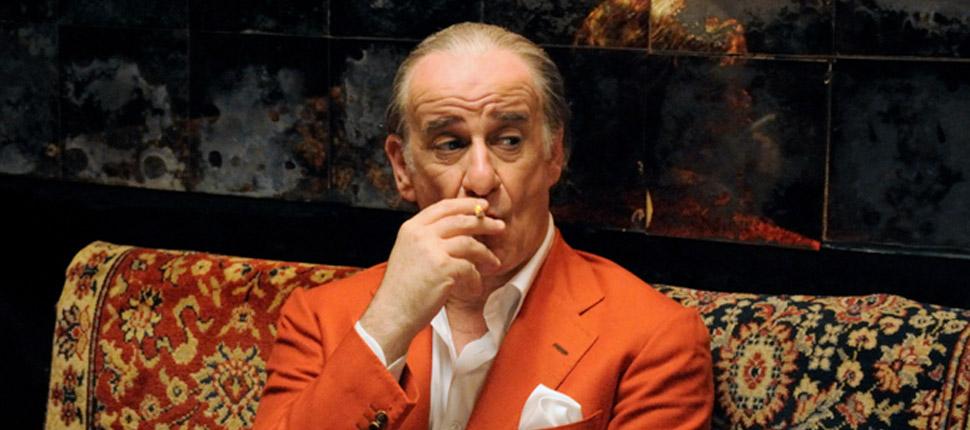

There’s so much mindless self-indulgence, rampant kink, and subversive weirdness going on in the inaugural shindig that it’s natural we should jettison the movie’s first ten minutes from our minds. But that’s also part of Sorrentino’s overall point: the bored, decadent, Roman socialites that comprise so many of the players in The Great Beauty’s background and foreground have undertaken a fruitless quest to find fulfillment in pseudo-intellectual sanctimony and an unending cycle of bacchanals. Yet despite their best efforts, none of them manages to find the contentment that they seek in the “blah, blah, blah,” that our hero, Jep Gamberdella, solemnly decries in the film’s denouement.

Perhaps dropping dead at the top of Janiculum hill isn’t exactly what most of us would describe as the pinnacle of contentment, but the tourist’s unceremonious passing underscores precisely what it is that Jep’s compatriots are missing in life. They inhabit a city so drenched in beauty that it can quite literally kill, and yet none of them has the capacity to recognize it. They’re disenfranchised, hollowed out, fundamentally unhappy with their lives and their home; it takes an outsider’s perspective to adequately underscore just how disconnected these people are from the world around them. They can’t see Rome for its cobblestone charms.

And there’s something inherently tragic about that. The endless parade of shallow bourgeois partygoers we meet in The Great Beauty lack any ability to appreciate the Eternal City’s venerable loveliness; those who can, or who are at least less disaffected than everybody else, find that Rome has come to serve as a mirror which reflects the ugliness of its upper crust, and so they decide to leave and make their fortunes elsewhere. Among this subset we have the meek Romano, perhaps one of the only people in the film Jep can call “friend”, who quietly bids our hero farewell and gets out of Dodge in the middle of a magic act involving a disappearing giraffe.

One moment, Romano is there; the next he’s gone. When Jep turns back around to see the trick for himself, the giraffe which previously stood in the dead center of the Baths of Caracalla has similarly vanished. The connection is hard to miss – Romano is the giraffe. Jep, on the other hand, remains, playing the role of dissatisfied observer to the rest of Rome’s various wonders and idiosyncratic excesses. Taken in total with everything that Jep goes through over the course of The Great Beauty’s narrative, Romano’s choice to uproot is far wiser than Jep’s determination to stay; Rome is peppered by corruption, the death of the younger set, spiritual decay, and the selfish hunger of its ruling class. Anywhere else is better than here.

That’s a testament to the strength of Sorrentino’s central thesis. His argument is so persuasive, so cogent, that we understand the need to escape Rome even as he dazzles us with his lens. The Great Beauty boasts such exquisitely photographed imagery that Sorrentino could have simply left out the exploration of wealth caste debauchery and let his movie serve as a stunningly rendered travelogue; apart from all of the previously mentioned landmarks, he takes us to the Via Veneto, the Parco degli Acquedotti, the Villa del Priorato di Malta, the Church of San Pietro in Montorio, and all the way up the steps of Saint John’s Basilica’s Scala Sancta, where Santa Maria prostrates herself on the cold ground and crawls, step by step, to honor the Passion of Jesus.

Maybe these monuments, memorials, and other various attractions don’t serve any deeper cultural meaning for a foreign audience – Italophiles or dedicated students of European history might recognize one or two of them – but that enhances Sorrentino’s intent instead of diffusing it. Through the unsettled, jaded lens that filters Jep’s worldview, all that we see of Rome looks amazing; these sights may not leave us keeling over, ready for the end to come, but we nevertheless stand in awe of what Sorrentino carefully chooses to show us. If The Great Beauty fails to leave us moribund, it succeeds marvelously at instilling in us a desire to casually stroll Rome’s streets, cataloguing every aqueduct, every museum, every church that we pass on by.

It’s important to note that The Great Beauty’s purpose isn’t to strike us dead, like our poor, hapless friend from the brief overture outside the Fontana; it only wants us to see what the aimless, moneyed hedonites of Rome’s citizenry are overlooking, and what Jep’s amoral indifference toward his surroundings and his fellow man blind him to. Rome, according to Sorrentino’s camera, is a place of emotionally fulfilling pleasures and limitless beauty – perhaps even the very same referred to in the film’s title (which is so multi-faceted that one could ascribe any number of meanings to it without being strictly wrong).

Arguably, The Great Beauty actually calls to the revelation Jep stumbles upon in his metamorphosis from bored, conceited playboy to enlightened, spiritually renewed novelist: that he, like all of us, leads a life of uncertainty, one where he knows not what he knows, what he feels, and so on. He’s able to let go of his concerns about his own mortality, his unresolved heartache over the young woman who broke his heart as a younger man, and finally dedicate himself to writing his second book. In other words, he’s free of his hang-ups, liberated from his pretensions, and capable of seeing the world as it’s meant to be seen.

But that’s the real key to Sorrentino’s headline, and why it matters little if at all whether we bring any familiarity with Rome and Roman culture into The Great Beauty with us or not. Ignorance of either turns out to be something of a gift, here; like the Asian tourist who ceases to be in the film’s opening sequence, we enjoy something akin to a purity of vision. We have none of the same baggage as the people Jep encounters and interacts with along his journey toward the ambivalent nirvana he attains in the film’s denouement. It’s the sublimity of not knowing that allows us to fully experience and enjoy all that Sorrentino and The Great Beauty have to offer us, from its lurid, exquisitely wanton parties, to its neverending parade of eccentric characters, to the immeasurably long, unbroken shot along the course of the Tiber river that supplies a backdrop for the film’s closing credits.

Just remember that in the end, it’s only a trick.