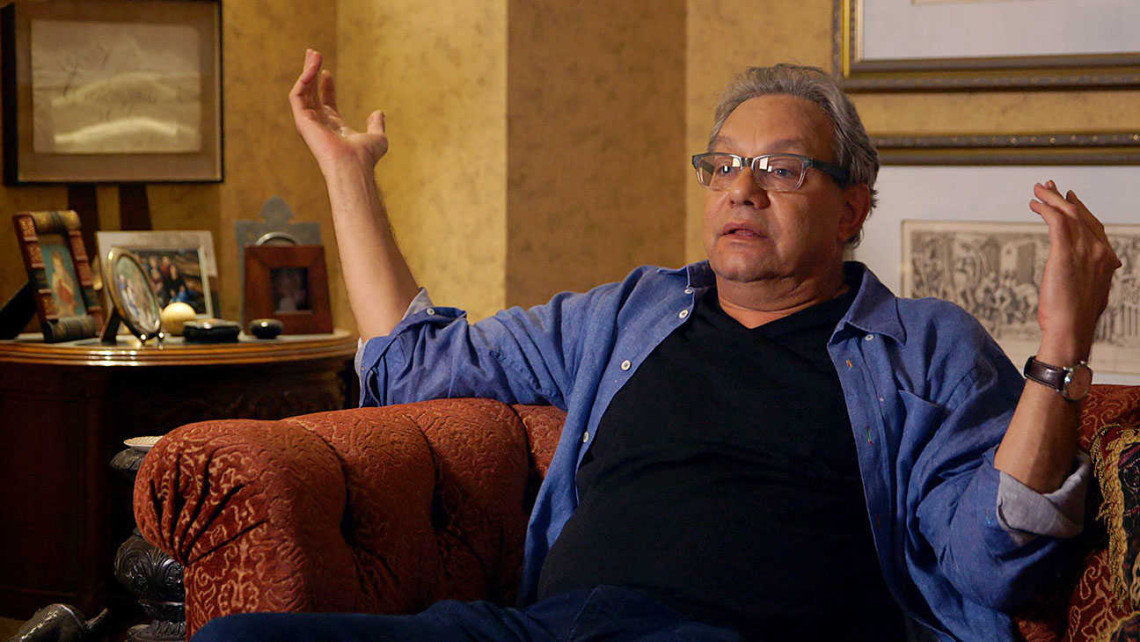

“In order to become a comic—pay attention—you have to love watching yourself die.” —Lewis Black

In the new documentary Misery Loves Comedy, funnyman Kevin Pollak interrogates the popular notion that comedians must necessarily live wretched lives to fuel their humorous insights. He really only gets to that fascinating subject in the last 20 minutes or so, though. Mostly, the film’s made up of generic talking-head segments with an impressive combination of A-listers and talents adored in comedy-nerd circles. While Misery does yield a handful of fun and eye-opening anecdotes—in one of the film’s most poignant moments, Martin Short recalls having a nervous breakdown on a park bench while walking with his wife—it tends to rehash the same generic sound bites. With clearly demarcated intertitles lumping together shared experiences, the likes of Amy Schumer, Jason Alexander, and Kumail Nanjiani recall learning how to make people laugh from mom and dad, getting kicked out of class for cracking wise, and bombing spectacularly onstage for the very first time.

The finished product feels a bit too cut-and-dried, but Pollak does address a pressing concern: How did this myth of the painted Pagliacci gain such common acceptance, and is there any truth to it? With Robin Williams’s heartbreaking suicide still fresh in pop culture’s collective memory, the narrative of the humorist belying a bleeding heart remains as potent as ever. In addition, documentaries Conan O’Brien Can’t Stop and Harmontown shed a little light on the flawed personalities of the late-night personality and the creator of NBC’s gleefully metatextual sitcom Community, respectively. Behind every open mic roils a hotbed of self-loathing, anxiety, pettiness and depression.

Or so the picture show might have us believe. While the sad-clown narrative certainly has a basis in fact, cinematic portrayals of stand-ups have done a lot to reinforce the inner turmoil the invariably fuels the fire of humor. The urtext of the tortured humorist archetype dates back to 1974, with Bob Fosse’s Lenny Bruce biopic Lenny, in which Dustin Hoffman channels the legendarily incendiary stand-up in all of his raging, dysfunctional glory. A compulsive truth-teller, Bruce pushed every button, leaving no taboo untouched. Though Fosse’s film plays it loosey-goosey with the particulars of Bruce’s life and minimizes the darker aspects of his personality, Lenny still addresses the man’s morphine addiction and turbulent relationship with his “shiksa goddess” of a wife, stripper Honey Harlow. Lenny posits Bruce as a martyr too ahead of his time to survive. The more vehemently he rejected his own celebrity, the more aggressively his followers foisted it upon him as the old guard clucked on the periphery.

Fosse predicates his film on a directly proportional relationship between the profundity of Bruce’s act and the swirling vortex of negativity that was his personal life. He’s not particularly subtle about it, either; Bruce works existential and sociopolitical concerns into his routine more liberally as the charges of obscenity pile up against him. By the point he got strung up for the umpteenth time on drug and public indecency raps, Bruce’s stand-up sets more closely resembled a court transcript than a series of jokes. For a screenwriter, Bruce’s mythos proves seductively appealing. The very act of performing in the stand-up mode is a writer’s dream, a natural showcase for the character’s inner workings and a fertile seeding ground for subtext. The paradox at Bruce’s core—to express profound sadness in a way that brings happiness to others—has endured through a variety of reproductions on the silver screen.

Surely Judd Apatow’s most personal film to date, 2009’s Funny People plays with many of the stock conventions Lenny first established, albeit it through a fictional buffer. Its main comedian character, George Simmons (Adam Sandler), isn’t a tormented messiah cut from the cloth of Hoffman’s Lenny Bruce, but there’s still a strong undercurrent of hurt and regret beneath the punch lines. Years before the events of the film, George slept around and destroyed his relationship with his fiancée (Leslie Mann). The interim years have found him spinning his self-loathing and bitterness into no-brow studio pap. An especially memorable scene in which he complies with a groupie’s mid-coital request that he sound the trademark call from his ubiquitous, soulless Merman franchise is both weird and deeply sad. Though the film ultimately takes the shape of a redemption narrative as George learns of a debilitating disease and struggles to scrape his life together before his time is up, he begins as a prick of the highest order. The unsavory Merman anecdote above closes off a scene in which George and his protégé Ira (Seth Rogen) bring a pair of fans home. In a typical move, George beds them both and turns Ira out in the cold. (That said, Ira is really no better; he hoards opportunities for career advancement offered to his friends for his own use.)

Funny People’s funny people may not be brooding, defiant artistes. Even so, they still cement the perception that the naturally funny among us must harbor some angst on the inside. The dramatis personae of Funny People have no reservations about stepping on whatever little people might line the path to stardom. And then, when that success is attained at long last, it’s more emotionally vacant than Charles Foster Kane’s Xanadu; George and Ira both suffer from a contagious case of chronic dissatisfaction. Naturally, the film ends on a downer: George can’t win back the one who got away and takes out his frustrations on a less-than-supportive Ira by firing him, sending him back to his joyless job at a supermarket. The closest thing to happiness that these broken men, these comedians, can find is a shared laugh with one another.

And then there’s last year’s Obvious Child, whose subversion of the tragic-comedian narrative wasn’t even its most revolutionary move; the film’s clear-eyed take on abortion launched far more think pieces. Still, protagonist Donna Stern provided a refreshing alternative to the usual on-screen stand-up. In a performance of realistic vulnerability, Jenny Slate brought the subject of Gillian Robespierre’s romantic comedy a mile-wide streak of decency. She’s certainly flawed: Commitment issues stall her inevitable fall into love with multi-night-stand Max, she’s a little self-involved, and she’s prone to self-destructive impulses. Still, Robespierre extends enough generosity to her leading lady that she ends up as someone the viewer might want to be around anyway. Slate’s portrayal is freed from the holy pain and base nastiness that defined Lenny, George, and Ira. She tries very hard, makes mistakes, learns a little, and continues to make mistakes. In other words, she’s human.

Though it makes few meaningful statements, Misery Loves Comedy does grasp the key truth that for the subjects of its many interviews, comedy is more than a job. As Joan Rivers pointed out to a lightly fictionalized Louis C.K. on an episode of FX’s Louie, it’s a calling. “Comedian” is a classification of personality, a codified set of tics and traits. The pictures has often suggested that that set must include warring self-pity and self-aggrandizement, repressed emotional baggage, and a crippling distrust of others. The truth of the matter won’t make for flashy screenplays, and it doesn’t create larger-than-life characters. For Donna, for Slate, and for the innumerable soldiers on a tour of duty through open-mic nights across the nation, it’s neither about exorcising personal demons through the cathartic release of a big laugh, nor getting another fix of that most potent narcotic, the crowd’s love. It’s about telling funny jokes. As if there could be a higher calling than that.

One thought on “The Agony of Comedy”

I wonder if the self-loathing trait being discussed here isn’t as crucial to being a successful comedian as it is crucial to being a long-lasting one. It’s one thing to be funny once, but maybe keeping the honesty cranked up after a few years requires a certain type of person? Enough comics have “lost their teeth” as they aged, no question.

Another point: it seems like the self-loathing comics are always the self-loathing comics, if you’ll forgive the tautology. I mean, no part of me is surprised that Lewis Black generated that Lewis Black quote. Where are the tales of Steven Wright’s massive internal struggles? Is Jerry Seinfeld that miserable all the time, too?