Something Old, Something New is a weekly feature that creates a double feature with a film released in the last few years and an older movie. These films contain aesthetic, narrative and/or thematic parallels that can erase decades of separation and show how ideas and styles echo across cinema history.

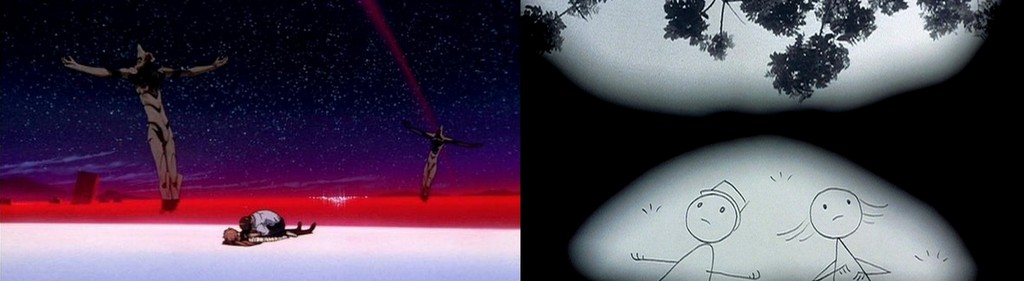

End of Evangelion and It’s Such a Beautiful Day use avant-garde animation techniques to respectively visualize extremities of depression and existentialism. Both are movies about the end of the world, outward manifestations of their mentally unstable protagonists. In fact, they could almost make for a seamless triple-feature with Lars Von Trier’s live-action Melancholia, a film that literalizes the cosmic sense of agony contained within something as small as the human brain.

The brains projected into these features may be even smaller than usual. End of Evangelion, a retcon and reinterpretation of the final two episodes of Hideaki Anno’s seminal anime series, Neon Genesis Evangelion, opens with the deep psychological scarring of the show’s protagonist, unwitting child soldier Shinji Ikari, well established by 26 episodes of television. Over the course of the show, Shinji—the neglected son of the head of a government organization that creates giant bio-mechanical beings capable of being controlled only by 14-year-olds in order to fight waves of invading aliens—cracks from the psychological strain of being made to kill by the military-industrial complex (via his own father) and from the transferred pain his “Eva” experiences from wounds.

Bill, by contrast, walks through the connected shorts that It’s Such a Beautiful Day comprises in a blackout haze brought on by a mysterious, pan-symptomatic mental illness. Memory loss, emotional disconnect and cognitive dissonance all seem to weigh on Don Hertzfeldt’s stick figure. Bill is tormented not by outside forces but his own fractured mind, cutting him off from the world around him via an animation style that stresses blotches of visible movement set against an otherwise pitch-black screen. Hertzfeldt himself narrates these myopic patches of consciousness, bridging gaps in memory and consciousness with a flat, disaffected recounting of events and moods. Hertzfeldt reads his narration like a physician recording his observations; the plain, matter-of-fact rhythm and language a vain attempt to clarify things for his wracked protagonist.

Occasionally, however, a sensory experience overloads the modest style and brings out the fullest of Hertzfeldt’s avant-garde technique. His use of various in-camera effects, live-action footage and more vividly realizes mental illness and, more broadly, the sensory experience of life like few other filmmakers have achieved. The thrill and fear of blossoming love, the hollow feeling of losing someone, and the general awkwardness of human interaction transcend the spare dialogue of the voiceover to connect directly into universal feelings. Hertzfeldt’s kaleidoscopic leaps into ecstasy and horror are reflected in the similarly brazen animation of Anno’s feature. Though the animation itself hews to more traditional cel shading, End of Evangelion proves no more typical as Anno uses his alternate ending (created to satisfy fans outraged with his original, entropic conclusion of the mecha show) as a means of venting even more splenetic agony, compounding the depression that leaked into his final episodes of the show with the pain of betrayal at the hands of his supposed admirers. Anno takes the doubting, even catechismic structure of the series’ final episodes and marries them to increasingly surreal sights as he callously destroys his creation.

As both films near their respective apocalypses, they offer opposing viewpoints on their expansive endings. Hertzfeldt, who pulls Bill away from an inevitably tragic conclusion (in a move right out of Murnau’s The Last Laugh), places the poor man on a happier path, an out-of-body experience of building intensity as the man fated to die becomes immortal. Yet Hertzfeldt deliberately pushes too far, finding buried in the euphoric reach beyond time and space something more despairing than the original ending. Anno, on the other hand, engages in outright nihilism, trading the psychological peace (if not narrative resolution) of the show for complete eradication. And yet, within Anno’s chilling, raw-nerve response to those who demanded more from him at the expense of his mental health, a faint shard of hope all the more visible for everything else being reduced to the primordial soup. That this whisper of optimism comes from the most prosaic and yet perhaps most disturbing image in the whole movie—the attempted strangulation of one of the two last people on Earth—proves as troubling as the bleakness Hertzfeldt finds in paradise.

2 thoughts on “Something Old, Something New: The End of Evangelion / It’s Such a Beautiful Day”

Love your write up on BEAUTIFUL DAY Jake, especially when it comes to the ending. My favourite film of last year by a mile, but talk about bittersweet. Really curious to see EVANGELION now – do you need to have watched the series for it to make sense?

Thanks Tom! And yes, you MUST watch the series first before seeing END OF EVANGELION. I think the DVDs are OOP but I watched all the episodes online. Have no fear, though, it’s only 26 episodes, and it’s one of the great works of popular art of the ’90s. If I placed it among my favorite films of the decade it would easily be a top 10 contender. Harrowing, gorgeous and devastating as it sinks ever deeper into its protagonist’s (and its maker’s) despair.