Miguel Gomes’ bifurcated Tabu is an ode to the Portuguese concept of saudade, a kind of nostalgia for something long gone. In its first segment, Tabu imbibes this unplaceable sense of loss in an abstract form, roaming around present-day Lisbon in a cocoon of privilege tinged with a vague sense of hollowness. Only when the second segment leaps back in time to tell the story of the old woman seen among the handful of characters does this feeling become clear: Tabu’s flashback reverts to Portugal’s last gasps of colonialism, linking the personal emptiness infecting the first act with the mourning of a lost empire.

That flashback, and its stylization, recalls Mikio Naruse’s 1955 masterpiece Floating Clouds, another story of passionate, doomed love tinged with the collapse of national superiority. Tabu’s Aurora (Laura Soveral as an old woman, Ana Moreira as her younger self) and Floating Clouds’ Yukiko (Hideko Takamine) are separated by class—Aurora enjoys luxurious wealth, while Yukiko served as a lowly secretary at the height of her fortunes—but they both personify the wistful ignorance of colonists and, eventually, their homelands’ respective shame.

But if the two characters share similar arcs of love kindled in an exotic locale and destroyed by the return to reality, their films handle those tempestuous romances in different ways. Floating Clouds, much closer in proximity to its national humiliation, stays rooted on its principal characters. Brightly lit French Indochina meshes with the darker tones of postwar ruin back home, but these subjective cinematographic touches comment first and foremost on the relationship at their center. But if Yukiko idealizes her time with Tomioka (Masayuki Mori) abroad, Naruse uses her romantic memories of that time as an ironic counterpoint for what is obviously just a fling in reality.

Irony abounds in Gomes’ film as well, though he frames much of his own juxtapositions less between his own aestheticized past/present splits than between the white colonists having their wanton fun and the native Africans who must bear this fatuous and ultimately destructive behavior. Gomes foregrounds Aurora’s torrid affair Ventura (Carloto Cotta) amid bustling servants whose obedience is tinged with a simmering resentment that rises to a boil as the whites’ actions disrupt an already tenuous harmony. Where Yukiko embodies Japan’s toxic sense of loss, fatally attached to false memories of a better time that must be dispelled to move the nation forward, Aurora becomes the principal agent of Portugal’s own loss, a visualization of the obliviousness necessary to be surprised when a colonized nation can take the chaotic inanity of its overseers no more.

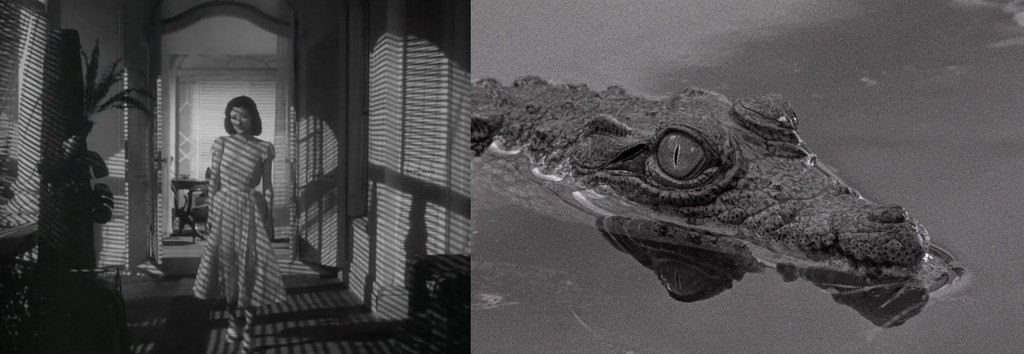

Nevertheless, Tabu’s harsher critique of colonial presence is offset by a more nostalgic stylization than the more muted, emotional terms of Naruse’s heartbreaker. Naruse intercuts between sunny recollections and gloomy, directionless present until the distinctions dissipate and the ideal image is erased. But the clear line between present and past in Tabu frames interpretive history as film history in reverse: the final act is silent but for a voiceover and filmed in grainier 16mm, while the present shows off rich, smooth 35mm.

An evocative prologue that features a man turning into a crocodile conjures comparisons to Apichatpong Weerasethakul, completing the reverse movement from a fondness for cinema’s own idealized past to a poetic, mysterious future. The social properties of nostalgia are eradicated in Naruse’s film, forcing its survivors to appreciate what they no longer have while pointing them forward, but Gomes targets nostalgia itself, in all its bourgeois applications.