Of the write-ups that have been published in the lead-up to its release, none have been more indicative of the confusion surrounding the nebulous status of Rogue One in the Star Wars franchise than the handful of guides to understanding where the new film fits into the series’ timeline. It’s the second of the new run of post-George Lucas, Disney-produced films, but not a sequel to the trilogy started with last year’s Star Wars Episode VII: The Force Awakens. It’s a sort of prequel, but one that only loosely connects with the characters and swashbuckling hero’s journey arcs from the trilogy that started in 1977. Rogue One is another sign of a growing trend of ancillary films that take place within the universe of an established franchise, instead of directly continuing that franchise. This inclination towards stand-alone stories rather than straight sequels or prequels was also exemplified this fall by the release of Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them, a story from the Harry Potter universe that is decidedly Potter-less.

I say ancillary rather than anthology (as Rogue One was designated when it was announced as the first in a series of stand-alone Star Wars films) for numbers of reasons. First, anthology films within franchises are not entirely new. They’ve been staples of long-running horror series—Halloween III: Season of the Witch, The Exorcist III, and the latter half of the Hellraiser sequels are only tangentially related to the franchises that bear their name. And the anthology has had a healthy revival on TV in recent years, with American Horror Story, True Detective, and American Crime Story presenting a new story each season connected only by each series’ particular thematic or genre concerns.

Unlike these example, Rogue One and Fantastic Beasts explicitly take place within their respective cinematic universes, and presumably stick to the history set out by the main films in those series. As well, both are based on throwaway references. Rogue One, set immediately prior to Star Wars Episode IV: A New Hope, follows the ragtag group of Rebel Alliance soldiers on a mission to steal the blueprints for the deadly superweapon known as the Death Star (an event mentioned in the opening title crawl of the original film). The Star Wars franchise even has something of a precursor to its series of stand-alone films in the former Star Wars Expanded Universe, a long-running (and onetime “official”) continuation of the saga contained mostly in a series of novels written by a number of Lucasfilm-sanctioned science-fiction authors. Specifically, the five-book Tales series (Tales from the Mos Eisley Cantina, Tales from Jabba’s Palace, Tales of the Bounty Hunters, Tales from the Empire, and Tales from the New Republic) are collections of short stories about minor characters and settings glimpsed in the original trilogy. Basing a film on the heretofore unanswered question of “how did Rebel spies steal the Death Star plans?” has a similar flavor to “how did Boba Fett survive being swallowed alive by the Sarlacc?” as seen in “A Barve Like That: The Tale of Boba Fett” from Tales from Jabba’s Palace. Meanwhile, in the world of Harry Potter and his alma mater of witchcraft and wizardry, Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them is a required textbook—the film version finds the book’s British author Newt Scamander scouring 1920s New York City for the aforementioned creatures.

In that spirit, these ancillary films function more like fan fiction, taking inspiration from their source material and exploring different facets of a pre-existing fictional world. And like fan fiction, ancillary films are not necessary continuations of a story or character arc . Much has been made of the “pointlessness” of both Rogue One and Fantastic Beasts in reviews, and certainly as pieces of storytelling they are entirely redundant. They add no further insight to the films that came before in their respective franchises. They are indeed pointless, save for the obvious commercial value in generating more revenue from an existing brand, though that’s hardly a betrayal of the “artistic purity” of the original films in either franchise. That is, Rogue One is hardly the first Star Wars film designed to sell toys. If ancillary installments are the new franchise filmmaking trend, then it appears that “pointlessness” is entirely the point, an excuse to spend more time with a beloved fantasy.

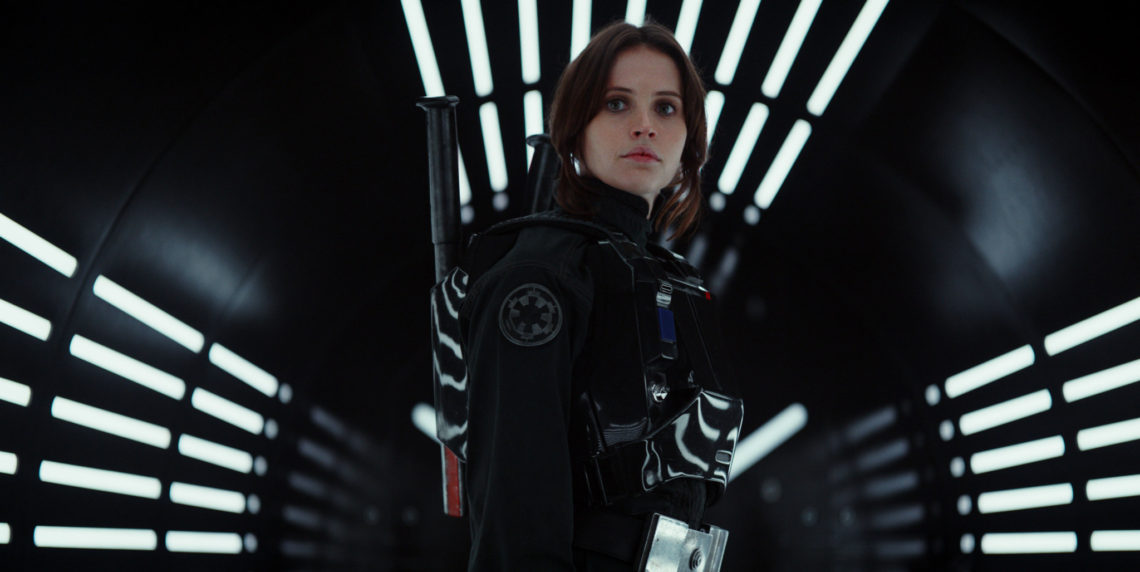

As such both films only succeed when they embrace their stand-alone nature, and both falter when they reach too far beyond those bounds. Rogue One has a perfect structure built into its premise, as a war film/heist movie hybrid set in a sci-fi milieu. The final act, which focuses almost solely on the Rebels’ clandestine mission, is the film’s most thrilling and satisfying segment, and could very nearly function as a short film about the sacrifice of military grunts in the grand scheme of a vast war. However, the rest of the film leading up to that is far too beholden to making cheeky references to the original trilogy. Familiar background characters make unlikely cameo appearances for no reason other than as a service to the franchise’s hardcore fans. The Death Star’s fatal design flaw is explained away as having been built into the weapon on purpose by a double agent, needlessly retrofitting an answer to a question that was never asked by the original film.

Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them does better in this regard, having very little to do with the Harry Potter series’ central conflict between The Boy Who Lived and He Who Must Not Be Named (understandably so, as it takes place 70 years prior to the other films). The movie’s most entertaining sequences focus on Newt and his newfound human (or No-Maj as in “no magic”) friend traipsing around the streets of New York in search of the missing creatures from Newt’s magical menagerie, as well as on the day-to-day details of wizarding life in the 1920s, like the back-alley wizard speakeasy where shots of “Gigglewater”flow aplenty. Where it fails are its ambitions beyond that simple set-up. Fantastic Beasts has been announced as the first in series of five films chronicling the rise of Gellert Grindelwald, an evil precursor to Lord Voldemort who will eventually face off with future Hogwarts headmaster Albus Dumbledore. As such, this film’s weakest moments are the attempts to built up the new overarching mythology. If ancillary films are the new sequel, why commit to another multi-film slog when there is a library’s worth of other magical textbooks to explore? Surely, it’s not difficult to imagine a sports movie based on Quidditch Through the Ages or refashioning Home Life and Social Habits of British Muggles as a comedic faux wildlife documentary.

If Rogue One and Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them portend a new wave of alternatives to straight prequels and sequels, the key to success seems to be in simplicity. Ancillary should be just that: a supplement to a larger tale. Grandiose ambitions can become easily tiresome when sometimes it’s enough to just want to spend a little more time in the fictional worlds we love.