As Hollywood grows more dependent on brand recognition outside of just stars, Quentin Tarantino is one of the few directors who can secure high budgets and wide distribution on name identification alone. Name recognition coupled with the financial and awards success of his last two features allowed Tarantino to release his most recent film, The Hateful Eight, in an initially limited, 70MM “Roadshow” engagement. Before entering wide release two weeks ago, where the film has struggled to find a broader audience, the film saw a record per-theater attendance in its first week in selected theaters. Even as Star Wars: The Force Awakens exponentially jolted towards box office ascendancy on post-Gen X nostalgia, Tarantino’s film recalls a cinematic longing of its own—for an era when the screens were big, the budgets bigger, and movies were events as legitimate and urgent as live theatre. But the deeper history of the roadshow release reveals a time very much like our own when studios panicked, gambled, and, finally, rolled over for a new generation. Tarantino’s roadshow spectacle seems like a recreation of, in the words of Star Wars’ own Ben Kenobi, an “elegant weapon from a more civilized age.” But its connections to the golden age of the Hollywood epic might just give us clues to the future of cinema.

When he appeared on “Jimmy Kimmel Live!” to promote the film’s release, Tarantino explained the lost appeal of the roadshow epic. The director spoke of a time when attending a “big movie” would have an overture and an entr’acte as if it were an opera or a Broadway show. “Usually,” he said, “the movie was a little bit longer than the general release version. No one has done this for a long time. I think it’s a little bit of a present for my fans.” It’s hard to doubt the sincerity of Tarantino’s decision. It was hardly a money-hungry move to make a few dozen US theaters install 70mm film projectors just to be able to screen his movie, let alone expect them to facilitate printed programs and an intermission. Discussion of the film’s roadshow screenings has treated its intermission with something akin to awe. It becomes a reason to go out to the movies again. But, like shared cinematic universes or 3D projection or, goddamn it, moving seats, the roadshow experience was never something designed with quality cinema in mind. What Tarantino’s careful narrative of nostalgia and scope fails to mention is that the roadshow represented an era of speculation, hype, and safe bets on big budgets equaled only by our own.

After the 1950s saw ticket sales plummet to a historic nadir, studios were scrambling to lure their audiences away from the hypnotic glow of television. The portrayal of television’s arrival in Douglas Sirk’s All That Heaven Allows casts the box as a pernicious parasite, reflecting an industry paralyzed by convenient mass media that could properly compete for audience’s attentions. While the TV set offers “life’s parade at your fingertips,” Sirk’s film implies, through Jane Wyman’s empty reflection, that this comes only at the cost of your soul. It’s an image all too real for Hollywood bean counters in post-war America. Previous box office gold like Bible epics and costume dramas were becoming more expensive and less guaranteed to turn huge profits. 1963’s Cleopatra was the film Steven Spielberg likely still believes is going to implode the franchise system, and the film industry along with it. Even as the top-grossing film of the year, Cleopatra cost so much to make and market that nearly bankrupt 20th Century Fox. The only thing that saved the studio was stumbling across the biggest film in history, 1965’s The Sound of Music.

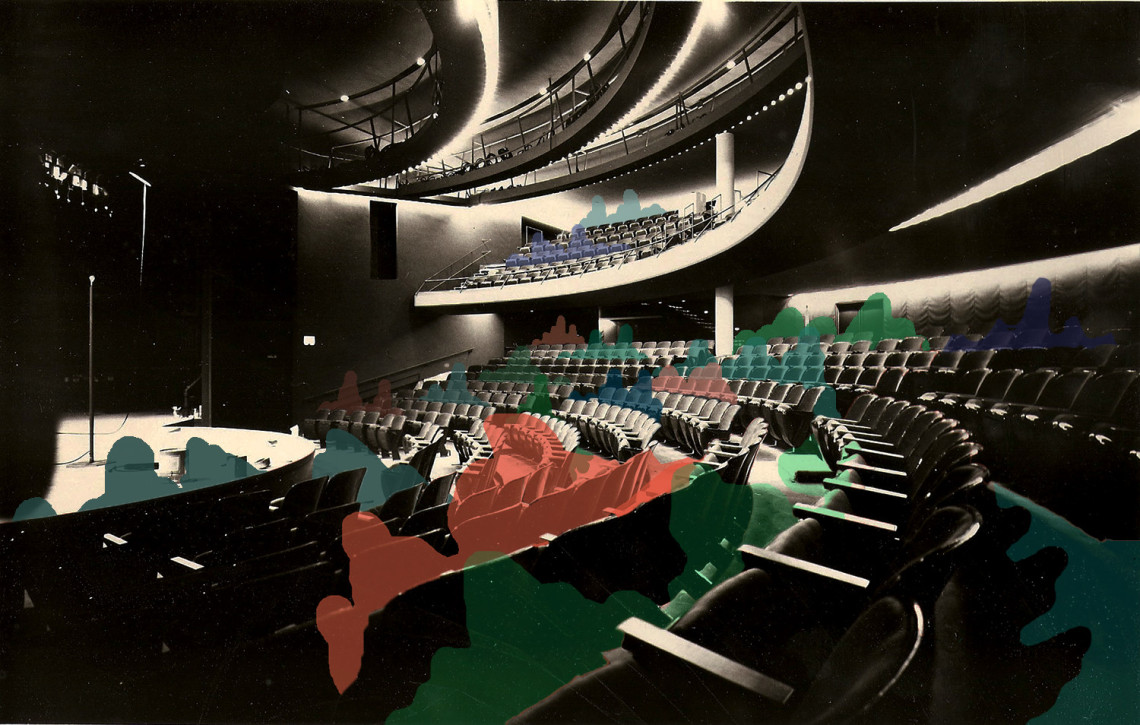

Robert Wise’s blockbuster musical smashed not just the ceiling of how much a movie could make, but how quickly it could do it. It had taken the previous all-time North American box office champion, Gone With the Wind, 26 years of revival screenings to earn what The Sound of Music earned in 18 months. This is a feat that Avatar achieved in roughly 7 months, and which Star Wars: The Force Awakens trounced in only 20 days. Like today’s franchise behemoths, The Sound of Music was aided by premium engagements and roadshow ticket prices. IMAX screens and 3D conversion might gouge modern ticket buyers, but they have nothing on the roadshow. Throughout the 50s, roadshow engagements like The Sound of Music treated films like stage productions. Seats were reserved weeks, if not months, in advance. Audiences paid up to double the normal ticket price in exchange for all the trappings of Broadway—from glossy programs to overtures, intermissions, and entr’actes, every ounce of which is evoked in Tarantino’s The Hateful Eight roadshow. But while The Hateful Eight played for only a few weeks in limited release, films of the mid-60s often played for months in limited venues of select cities, stoking hype until eventual expansion into wider release. And while there had been roadshow hits before 1965, The Sound of Music (along with My Fair Lady the year before) opened an unprecedented barrage of speculation and imitation.

When today’s studios announce years’ worth of upcoming tent poles, they’re only following the precedent set in the late-60s. Julie Andrews’ singing nun was still in cinemas when Paramount announced four roadshow musicals, while MGM raided its own back catalog for musical reboots of moribund properties like Goodbye, Mr. Chips; The Great Waltz; and Random Harvest. Some shared the fate of Sony’s recently canned second iteration of the Andrew Garfield-led Spider-Man movie universe, like a never-produced musical version of Rebel Without a Cause. Others were accompanied by massive advertising blitzes. Fox’s 2-year ad campaign for 1967’s Doctor Doolittle included soundtrack recordings, cardboard standups in restaurants, and $200 million in retail material. Months ahead of its own release, 1967’s Camelot licensed everything from cosmetics to model kits to bird cages, as well as the requisite soundtrack. Yet the period Tarantino is referencing wasn’t just one of the most speculation-driven in Hollywood history. It was also one of the most tumultuous.

In response to this summer’s release of the universally maligned Terminator Genisys, Allison Wilmore rued the modern blockbuster as “[a machine] built on anticipation.” Movies aren’t movies anymore, it would seem, but big-budget imitations of serialized television. Tarantino’s return to celluloid and marathon running times feels almost like an antidote to what Mark Harris (who literally wrote the book on old Hollywood’s death throes) warned of as the nearing of something “big and dark and annihilating.” But, just like the plot of a Terminator movie, this has all happened before.

As the roadshow era advanced across the late-60s, films distended in size, racing to match their own marketing. If audiences loved the dozen or so songs in The Sound of Music, they were going to get 17 full-on production numbers in Wise’s Star! (1968). If the rights to Hello, Dolly! cost $2 million, then it was going to include a parade scene on par with the largest single sequence ever recorded for a motion picture. Doctor Doolittle jammed hundreds of trained animals down audience’s throats. Paint Your Wagon dug miles of tunnel in the Oregon wilderness, built an Old West town on top of it, and then knocked it all over. “There seems little doubt that the really big film (is) here to stay,” wrote the LA Times’ Charles Champlin at the height of the roadshow craze. “They justify financially the greater length, high costs, starrier casts and whatever else is big about bigness.” This fatigue of scale lends a certain irony to the misplaced criticism of The Hateful Eight’s comparative intimacy, in which detractors focus on some kind of assumed dissonance between the widescreen format and the script’s cabin-bound theatricality. Outside of Tarantino pointing out that the 1950s were full of widescreen film adaptation of plays like Hat Full of Rain and Bigger Than Life, this criticism echoes a strange amnesia. It’s as if there is a longing for some kind of mythic, widescreen past. But what would this imply people wanted from The Hateful Eight? For it to be a purely landscape film?

The cynical marketing ploys of the 60s seem almost quaint to us now. But by the end of the decade, audiences were catching on. The epic musicals began to seem like the pale imitations of Broadway that they were. Actors were cast for name recognition regardless of musical ability, while believably unbelievable stage backdrops were supercharged to obnoxious scale in studio backlots. Even when the results were suitable for audiences, the effect was short-lived. As crowds today are drawn to the special effects and strained continuity of superhero movies, audiences turned out in droves in 1968 to revel in the spectacle of Barbara Streisand in Funny Girl. Just one year and an Oscar win later, the novelty of her brassy persona left Hello, Dolly! playing to empty engagements nationwide. We talk about “franchise fatigue” today, but in the last quarter of 1968 alone, 12 roadshows were prepped for release.

The format produced plenty of wide-canvas classics, including 2001: A Space Odyssey and Patton, the type of movies Hollywood is decried for not making anymore. But these films were the exception of the era, not the rule. We conveniently forget derivative dreck like Sweet Charity, Half a Sixpence, and Darling Lili, every one of which was advertised with as much fanfare as any Marvel Studios movie today. Ice Station Zebra, Battle of the Bulge, and The Sand Pebbles–you don’t fondly remember these films for the same reason no one will fondly remember Thor 2 in 60 years. Not because they were bad, but because they were furniture. They existed because cinemas existed and the people with interest in those cinemas needed something to put in them. They worked until the cost required to make epics led to the weary dissolution of the very system that had created them. Thousands of extras in period dress gathered to shoot Hello, Dolly! on the Fox backlot that, just a few years later, would be sold off piece by piece just to keep the lights on.

The success of 1960s roadshows, like the success of special-effects-driven franchises today, was predicated years ahead of time, meaning that their arrival couldn’t keep up with the rapid social change of the late-60s. A string of roadshow flops not only led Hollywood to the brink of destruction but looked increasingly archaic against the growing popularity of youth-driven entertainment. If the teenage baby boomers of 1968 had looked up from the streets of LA, they might have seen the two-blocks-long billboard advertising the 3-hour long Julie Andrews vehicle Star!. But they were too busy lining up for Bonne and Clyde and The Graduate. And, fatigued by franchise extravagance, it’s tempting to long for some latter-day Paint Your Wagon, an expensive disaster whose crash will reverberate through the coffers of the speculators and usher in an era of creative exuberance.

While the success of low-budget, edgy films destabilized roadshow epics in 1968, the same strategy won’t work twice–not in an era of global corporate synergy. Hollywood might have given birth to the radical voices of New Hollywood in 1969, but it only did so because expensive failures had left the industry devastated. Craft union membership, from stagehands to lighting technicians, reported 80% unemployment as the decade turned. Even beyond similar rates for actors and writers, a string of losses by every major studio led to downsizing in every department. Franchise success is, of course, not synonymous with studio investment. To take just one studio as an example, Warner Brother began to hype their rollout of superhero films in late 2014. Much less press was given to the simultaneous downsizing and the layoffs of hundreds of employees.

It wouldn’t be much fun if Tarantino hedged his roadshow nostalgia with discussions of unstable economic systems. Much as the story of his own origins have been meticulously rewritten over the past 25 years–just see if his bragging about his Pulp Fiction screenplay Oscar win ever mentions his estranged writing partner and co-Oscar-winner Roger Avary—so too has his narrative of the past. Unless you were born in, say, 1950, you don’t remember the heyday of the roadshow. And Tarantino, born in 1963, doesn’t remember it either. Only 10 other films in history have been shot in the Ultra Panavision format utilized for The Hateful Eight. The lenses used to shoot the film were pulled out of storage at Panavision, having seen no light since 1966. Just as his previous two films employed liberal revisionism with American history, the meta-narrative of The Hateful Eight allows us to imagine a time before digital—before a ticket to a cinema became, in Tarantino’s words, like “renting a chair for two hours.” We can have a roadshow experience and pretend it hearkens back to a time when big didn’t mean crass.

And yet it’s hard to resist this revisionism, as it seems to have resurrected something almost nonexistent in the age of binge-watching and instant downloads. A roadshow screening of The Hateful Eight offers art you can’t have at any moment—art as something bigger than its status as a commodity. Here is an experience you can only get at a designated time in a designated place, and only properly (as stories of some of the film’s initially disastrous screenings have attested) at the hands of a skilled projectionist who remembers the lost craft of the projection light and the reel change.

It’s impossible now, in the nascent months of 2016, to anticipate what, if any, impact The Hateful Eight’s successful roadshow screenings will have. Will the theaters that installed 70mm projectors to show the film begin ordering film prints for revival screenings? Did they lease the projectors or buy them? Will a young generation be influenced by the experience to resurrect the analog fidelity of film? All that is clear is that Tarantino’s trick of exhibition worked in the short term. He convinced audiences to experience something new with all the ethereal qualities of memory and place. We demand that our entertainment possess the same texture as our memories. It was the promise made by the marketing of Star Wars: The Force Awakens—a promise that you would be able to feel the way you felt when you were young and you received all experience through a filter, as if through windows streaked with rain.

Maybe that’s why Todd Haynes’ Carol connected with so many film critics. Beyond just being set in the past, it feels like a feverish memory—the edges of its images diminishing into dreamy falloff. Rooney Mara’s eyes long through rain, through windows, sometimes both of these veils, and we associate with that longing an immediate history. It is as if this is a place that we have lived in dreams. If the cliché verb of a trailer from the 1950s was “Experience!”, the verb of our own advertising is “Recall?” Looking out across 2016 could instill existential dread, one weekend after another of our contemporary answer to the Roadshow asking us that very question. Do you recall these characters? Tarantino seems to be asking, “Are you as exhausted as I am? Do the baubles cease to thrill you?”

Tarantino himself even admits in interviews that, disconnected from the experience of going to see them, he likes very few of the roadshow-era films. What is fascinating is that he borrowed the speculative techniques of the past to combat the speculative techniques of the present. Listening to producers issue their franchise schedules, it’s hard not to mistake their arrogance for prophecy. Big-budget, research-driven entertainment has always been with us, and it will never go away. But the franchise machine is no more invincible today than the roadshows of 1966. It’s a cultural comma masquerading as a definitive period. And as a wise man once said, “If it bleeds, we can kill it.”