It’s time to kiss 2014 goodbye (or kick its ass out the door, depending on how well your year went) and furiously compile our Best-Of lists, as film people are wont to do. Obviously most people focus on ranking the best new releases of the year (“release” being an amorphous term, given the way smaller films get brief, menial Oscar-qualifying runs that are over before you know it, i.e. Mommy), but we here at Movie Mezzanine are not so narrow-minded. Real film lovers know that the best part of any given year is the restoration and rerelease of older movies, and, as technology gets better, and formerly obscure films are exhumed from the catacombs, the hidden gems of world cinema have never looked more lustrous. We put together a list of the five best restorations of 2014, not taking into account the special features or fancy packaging (indeed, one of the following films doesn’t even have a single special feature included on its Blu-ray release).

Macbeth (1971) | Directed by Roman Polanski

While Criterion admittedly put a lot more love into their stunning Tess set, which includes a booklet of essays and some really great behind-the-scenes features, their resurrection of Polanski’s brave Macbeth is the more necessary addition for cinephiles. (It’s also the better film.) Though it sadly lapsed out of the public consciousness, this bloody, beguiling fuck of a film is a landmark accomplishment that, akin to The Bard’s original tale, seems unscathed by the tests of time. By now the story of Polanski’s pregnant wife and the Manson murders is infamous, and Polanski’s anger and sorrow seep into every scene of the film; a sense of visceral horror, of impermanent life and permanent loss, pervades and propels Macbeth. Cryptic and caustic, some might say cruel, Polanski’s adaptation depicts the bellicose arrogance of the title character, played with subtle complexity by Jon Finch, with more tragic, lacerating severity than any other Shakespeare film. You can feel the guilt weighing heavily on Finch, and see it gradually purge the humanity from his face. Through chicanery, witchcraft, and so many murders most foul, Finch’s Macbeth ascends to the throne, a craven man become king. Power here is all-corrupting, and no one is impervious to its seduction. Polanski directs the hell out of this, experimenting with Scope for the first time, masterfully melding sound and vision to create a hallucinatory vision of greed and treachery. Its ending is arguably just as cynical as Chinatown. The Third Ear Band’s sparse, atonal psych-folk score writhes like a departing soul, and that final confrontation between Macbeth and the man not born of woman packs a gut-punch wallop.

Sorcerer (1977) | Directed by William Friedkin

Decades before the post-Nolan movie landscape was oversaturated with “gritty” reboots and “dark” blockbusters, Billy Friedkin was crafting rabid little monsters on the studio’s dime—films so nasty, visceral, and gnarly you could practically reach out and scrape dirt off the screen. If True Grit wasn’t already taken, it could have been the title of Friedkin’s autobiography. Sorcerer, a fabled failure that most moviegoers hadn’t seen until this year, hit theaters in the wake of Star Wars and went belly-up pretty quickly. Friedkin blamed Lucas’ behemoth for killing “serious films,” an erroneous assertion gadfly extraordinaire Peter Biskind perpetuated in his riotous book Easy Riders, Raging Bulls (a classic piece of tabloid journalism penned with so much flair, you kind of forgive its trespasses and just enjoy the ride). A big-budget remake of Henri-Georges Clouzot’s classic Wages of Fear, Friedkin’s film depicts a group of men stuck in a forlorn, God-forsaken country transected by an oil pipeline and ruled by the oil owners. Each man is on the run from some sort of life-threatening trouble or incarcerated by the local government (terrorism, fraud, murder, the usual suspects), and to earn the capital to get away, they all embark on a mission seemingly orchestrated by Sisyphus: they must transport nitro glycerin (that stuff that explodes when you touch it) across several hundred miles of rocky backwoods roads in rickety old trucks. Friedkin includes an extended series of prologues to add more of a human factor to the proceedings, but the real draw here is the grueling suspense and existential dread. Grainy and glorious, Sorcerer’s new transfer is one of the finer, most natural-looking restorations of a New Hollywood film (look at the Blu-ray of Friedkin’s The French Connection as a comparison, yuck). Roy Scheider, New Hollywood’s non-leading man par excellence, lends an air of tragic desperation to the film. And Tangerine Dream’s ethereal score is extremely Tangerine Dreamy. Sorcerer stands out from other ’70s thrillers because it’s suffused with relentless despair; even if these men survive their perilous journey, which is unlikely, they’re still heading back to ruined lives, with bounties on their heads. They can’t win.

Eraserhead (1977) | Directed by David Lynch

Filmed over the course of five years on the American Film Institute lot, David Lynch’s debut feature exists in a timeless, ageless vacuum, a monochrome hallucination set in an industrial landscape. Describing the alleged story of Eraserhead is pointless, as is trying to analyze every ineffable quirk (Lynch would have a lark at the expense of critics and academics in Fire Walk With Me, in a scene involving the exhaustive, overly-complex deconstruction of ostensibly meaningless actions). Eraserhead isn’t something you watch as much as it is something you experience, let envelope you, suffocate you. With some of Lynch’s most articulate compositions and perverse images (that baby! those chickens! that woman and those sperm-like…things!), the film remains a bastion of nightmares. It is not a flick you watch inebriated, lest you enjoy never sleeping again. The restoration looks stunning, but it sounds even better: the grinding and whirring of machineries and gears mingle with sustained electronic noise, and rarely does a moment of silence pass without some sort of interference. If you have the money to buy high-end surround-sound speakers, this is the reason to do so. And when you do, please invite me over.

Picnic at Hanging Rock (1975) | Directed by Peter Weir

Peter Weir’s career has careened from beautiful to baffling, with certifiable classics (Gallipoli, Master and Commander) scattered about a spread of lamentable near-misses (Witness), quirky hits (The Truman Show), and gross sentimental claptrap (Dead Poets Society). But his crowning achievement, and maybe the crowning achievement of the Australian New Wave, is his ethereal adaptation of Joan Lindsay’s novel Picnic at Hanging Rock. Based on an inexplicable true story, the film depicts the enigmatic disappearance of several beautiful young girls. The actresses are all aces, especially Anne Louise Lambert as their unofficial leader, and Karen Robson, who has a strange tendency of tilting her head and reading her lines in a stilted, unnatural way, as if she’s perpetually waking from a dream. (“Doomed to die, of course,” she intones.) There’s a unity of impression here, as every shot, every detail seems to lead us closer towards the inevitable outcome. (Poe would be proud, or drunk, or both.) The editing and use of double-exposures rival those used by Coppola in Apocalypse Now, and Weir sustains a tranquil rhythm throughout. An uncomfortable exercise in atmosphere and formal proficiency, Picnic at Hanging Rock is not for those who need their mysteries answered. Closure’s for suckers.

And, because it’s the Holiday Season, here’s a bonus film:

Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me (1992) | Directed by David Lynch

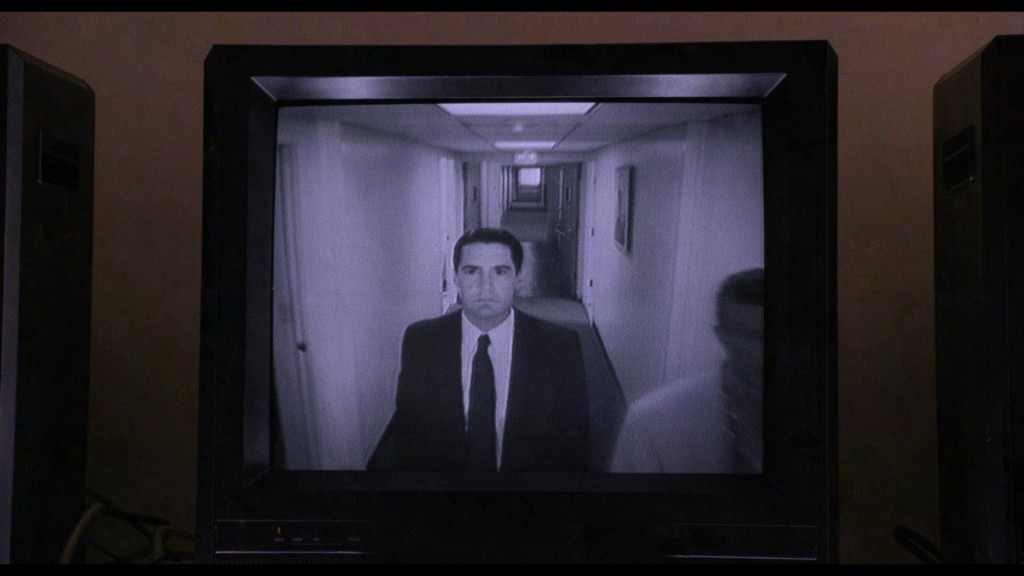

Fire Walk With Me was, until very recently, only available on shoddy European home media, pulled from a lackluster transfer. Fans pined for a decent Blu-ray release–or a decent DVD release, for that matter–for years, to little avail. While the film still hasn’t received its own standalone release, it is included on the gorgeous Twin Peaks: The Entire Mystery boxed set, and it’s probably the standout feature. The first five images in David Lynch’s polarizing film are, in order: a digitized writhing sea of blue that, as Lynch pulls the camera back, is soon revealed to be a television tuned to static, which abruptly ruptures into sparks in one of the single best jump-scares of Lynch’s career; a body, wrapped in plastic, drifting down a sinuous Oregon river; a close-up of Lynch’s face, framed against a painted forest background; a wider shot of Lynch against the forest background, yelling to his secretary to get Agent Chester Desmond; and Agent Chester Desmond handcuffing, in Lynch’s words, “two very buxom prostitutes” in front of a school bus of screaming children. Such is Lynch’s brilliant, brazenly uneven addendum to Twin Peak. It’s a genuine Twin Peaks movie for 20 minutes or so, rife with off-beat humor and inexplicable weirdness, before delving wholly into darkness. Fire Walk With Me benefits from shacking the shackles of network television, as it fully submerges us in the haunted, lugubrious world of Laura Palmer. Oscillating between Lynchian humor, Lynchian horror, and that singular Twin Peaks familiarity, Fire Walk With Me is the outlier in Lynch’s filmography, an oddity in a oeuvre of oddities.

Here are some more excellent restorations and rereleases from 2014, in no particular order: Tess; My Darling Clementine; The Texas Chain Saw Massacre; The Foreign Correspondent; The Night Porter; Thief; All That Jazz; Phantom of the Paradise; Ms. 45; Robocop; [SAFE]; The Conformist; and Criterion’s two monolithic, masterful box sets, The Essential Jacques Demy and The Complete Jacques Tati.