On the edge of 2017, in what most people would call the holiday season but experienced cinephiles know to be list-making season, it’s a natural compulsion to look back at the year in film and try to connect a thread between pop culture and life, how what we watched reflects what we did, and how what happens in life influenced how we view movies. In 2016, as has become the custom in recent years, franchises and superhero movies again ruled the American box office. It struck me that Americans don’t seem to have much of an affinity for regular people doing regular things, or average people taking on impossible-seeming tasks, or communities of people working together to fight injustice, and so on. No matter the cause, we seem to have focused solely on the story of one or two or five highly skilled heroes (or anti-heroes) saving the world from ultimate evil. It’s a fine way to escape, but where does that leave us in the real world?

If we can idolize superheroes for mindless entertainment, we can just as easily dismiss them as disconnected from the real world. Sometimes they need to be a reflection of reality, but sometimes they should reflect our best possible selves, because if movies have the power to take us to some other place, why shouldn’t it be a better one? As cynical as I can be, I also believe my best self to be optimistic, and I always look for hope, if not exactly happy endings, in movies. And so, as the year comes to a close, I was struck by the similarities of two of my favorite films of the year, Stephen Chow’s The Mermaid and Hideaki Anno’s Shin Godzilla, and the ways these two foreign films sent me strength to make it through another post-election/pre-inauguration day in America.

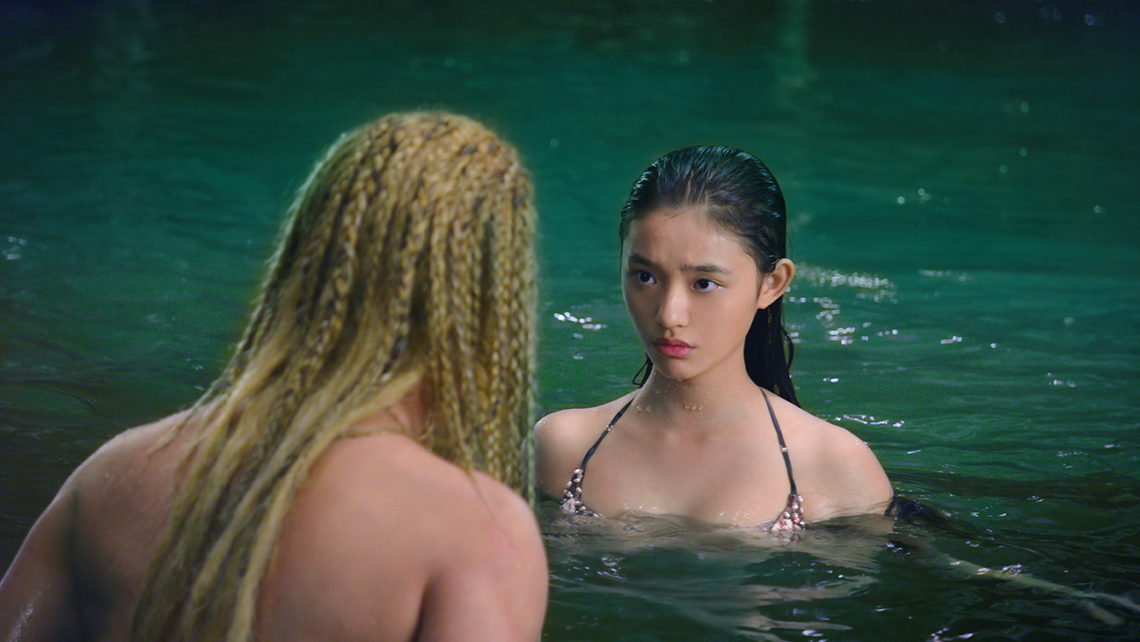

The Mermaid is a live-action cartoon with Technicolor costumes and mermaid fins, set against bright blue-and-green water and animated octopus arms. The wonky CGI is charming and the 3D makes it feel like a carnival ride, an immersive experience that is all the more painful when the action turns violent. The 2D Shin Godzilla, by contrast, spends most of its run time wallowing in the whites and navy blues of office interiors and suits, which makes the explosion of purple nuclear breath from Godzilla’s entire body and the ensuing fires feel like a shock. As visually different as these films are, both employ their respective aesthetics to make their mythical worlds, blending the fantastic and the mundane, feel vivid and immediate. But there’s another crucial thematic convergence between the two: They both choose to embrace optimism about humanity even as their characters sometimes act in unsavory ways.

In The Mermaid, a wild young businessman named Liu Xuan (Chao Deng) buys a wildlife preserve in order to build condos on it. With eyes set only on money, he uses a sonar machine to kill off the sea life, unknowingly threatening a small community of merpeople. In a hail-mary pass, they send a young mermaid, Shen (Jelly Lin), to find the man and kill him. Instead, after a series of mishaps, the two fall in love. This intimacy forces Liu Xuan to realize that he’s made a mistake, that his thirst for wealth has left him lonely. In the end, he turns off the sonar and saves Shen from a shockingly violent attack on the mermaid colony, and like all fairy tales, everything works out pretty well in the end, and we all learned some lessons along the way. Love is more important than money, and if man wants to spend his life enjoying that love, he has to respect the environment. It’s a novel and possibly naive statement to make, that reaching out in order to help someone understand might help you. The idea isn’t to sympathize with your oppressor but force them to sympathize with you, to let your guard down in order to connect. Getting close enough to someone to see them as a person makes it much harder to dismiss them. Once a fish becomes something that walks and talks just like you do, you begin to see yourself reflected in them. If The Mermaid doesn’t provide a realistic answer to our problems, it at least shows that there is still room in the world for change, that even greedy millionaires have the capacity for growth.

Shin Godzilla rests in similar territory—epic battle against an oppressor—but takes a different approach. Instead of giving a face and a nice suit to the horror, Godzilla is stripped of any personality he might have had in previous installments. The movie is so focused on the human element that Godzilla becomes more like an object, merely a reason to show how the characters react. As a satire of the government response to the 2011 earthquake and tsunami in Japan, it makes sense that he should resemble nothing more than weather. Character development, however, is minimal, with personalities defined mainly by quirks and facial expressions rather than names or story arcs. That’s not a criticism in this case, though, because all of these individuals are part of a collective—scientists and government agents, yes, but above all, human beings. It’s part and parcel of a vision in which all the characters are equalized, in which we want all people to be saved. There’s something almost daring in how focused this movie is on sympathizing with each person, emphasizing the importance of how they work together. Even the most obvious targets are given quirks that humanize them—like a lazy bureaucrat who orders noodles instead of making decisions—and we understand that some people are just not able to process a crisis. Shin Godzilla believes we are capable of rising above differences to serve a common good, and that in an emergency our best selves will be revealed. This is all enhanced by Anno’s choices to put cameras on anything from the seat of a rolling chair or behind a laptop screen, so fully immersing us in the action that we feel as if we are right next to all the scientists in conference rooms, scrolling through tweets for photos and information, watching as it morphs into a bigger and more powerful monster. As exciting as Anno’s camera antics are, there is no glory in what they’re doing. It’s just a parade of people doing their thankless jobs, frantically but without heroics. Even the climactic scene where Godzilla is incapacitated is depicted less as a bombastic rah-rah victory than a sigh of relief, the characters all realizing how close we came to the end, an acknowledgment of the rebuilding work yet to be done. If Shin Godzilla is an indictment of the way the Japanese government handled real-life disasters, the film still remains optimistic toward our ability to do better next time.

If both The Mermaid and Shin Godzilla are innovative in their use of digital technology and visual style, they may be equally as innovative in their insistence that a better world is possible. In what the internet has dubiously crowned “worst year ever,” it’s tempting to think that with the simple change of a clock, a new horizon will be visible, that we will somehow be more able to handle the crises facing us. It’s a bizarre line of thought, almost optimistic but undeniably naive, offering no advice beyond simply waking up on January 1st with a sense that something is over and done with. It isn’t over, of course, and if Hollywood cinema in 2016 was about escapism or wallowing in suffering or the triumph of some godlike strength over cartoon evil, Shin Godzilla and The Mermaid provide examples to follow within that escapism. Ironically, they’re both totally ridiculous—even though both are heavily inspired by real-life environmental issues—but it is with these images of fantastical beasts, mermaids and monsters that they manage to cut to the core of humanity, and provide hope in the face of evil that is utterly unbelievable and yet entirely real.