Over the past few years, the Walt Disney Company has chosen to lean hard into its various brands, especially in its film division. To define something you see in theaters as “a Disney movie” is no longer a signifier of a straightforward animated movie; it could mean a Pixar movie, a Marvel movie, a Star Wars movie, a Walt Disney Animation Studios movie, or more. This year alone, the Walt Disney Company is releasing 14 films, few of them without a specific brand of some kind; even the original films Zootopia and Moana (the latter opening in November) are marked by being from the company’s animation studio. Among Disney’s six live-action films this year that don’t feature Jedis or superheroes, one is a Roald Dahl adaptation (the upcoming Steven Spielberg film The BFG), and only two are wholly unbranded: The Finest Hours, which all but vanished from theaters earlier this year; and this fall’s prestige-y Queen of Katwe, a based-on-a-true-story picture starring Lupita Nyong’o and David Oyelowo, directed by Mira Nair.

The other three all belong to a burgeoning subgenre of Disney movie: live-action remakes of preexisting animated films, which themselves are typically based on preexisting material. This week marks the release of Jon Favreau’s adaptation of The Jungle Book, which owes as much, if not more, to the 1967 animated film as it does to the books by Rudyard Kipling about the man-cub Mowgli and the various animals he encounters in the jungles of India. Next month, we’re getting the live-action Alice in Wonderland sequel, Alice Through the Looking Glass, that no one asked for. And in the late summer, Disney will release Pete’s Dragon, a redo of the 1977 film, this one starring Bryce Dallas Howard and Robert Redford. The Jungle Book, specifically, is the third Disney film in three consecutive years to take partial steps to being a direct remake of its antecedent, following in the footsteps of Maleficent (2014) and last year’s Cinderella. Like those films, it stumbles because the people involved aren’t willing to fully commit to either making a near-shot-for-shot remake or going in a completely different direction.

There have already been, and will be many more, notices written regarding The Jungle Book’s visual pleasures. Though comparisons to James Cameron’s 2009 opus Avatar are stretching it, there’s no doubt that The Jungle Book is the most accomplished and dynamic of Disney’s live-action remakes—not a visual tire fire like Alice in Wonderland, and mostly incorporating its computer effects decently alongside the live-action elements (the most obvious of those elements being Neel Sethi, who plays Mowgli). The cheeky statement at the end of the closing credits—“Filmed in Downtown Los Angeles”—is a good final chuckle because of how seemingly realistic the jungle of this film appears. These effects never reach a point where they surpass the lush backgrounds and illustrations of the 1967 film, but they’re not trying to copy those backgrounds. They stand on their own solidly.

Where Favreau, screenwriter Justin Marks, and the rest of the crew take half-measures is where the half-measures occurred in Maleficent and Cinderella: with the songs. Maleficent, of course, is telling the story of Sleeping Beauty from the perspective of its presumed villain, yet the film’s highlight is the scene where Angelina Jolie’s horned fairy places a curse on baby Aurora, the dialogue matching up with the 1959 original. It’s the closest it gets to a Van Sant-style shot-for-shot redo of a memorable sequence. Cinderella, like The Jungle Book, is a more straightforward retelling of the story we know from earlier Disney animation; even in the 2015 film, the goodhearted would-be princess has chittering mice as friends. Maleficent, however, foregoes the majority of the songs from the 1959 film Sleeping Beauty, with the exception of Lana Del Rey’s sleepy cover of “Once Upon a Dream” during the end credits. Cinderella goes a bit further, tiptoeing around its musical forebear in dialogue: Helena Bonham Carter’s toothy fairy grandmother stumbles over the iconic magical phrase “Bibbidi-bobbidi-boo” before transforming Cinderella into a fetching maiden in a fancy blue dress. But there, too, any songs—both “Bibbidi-Bobbidi-Boo” and “A Dream Is A Wish Your Heart Makes”—are relegated to the end credits, performed by Carter and Lily James, respectively.

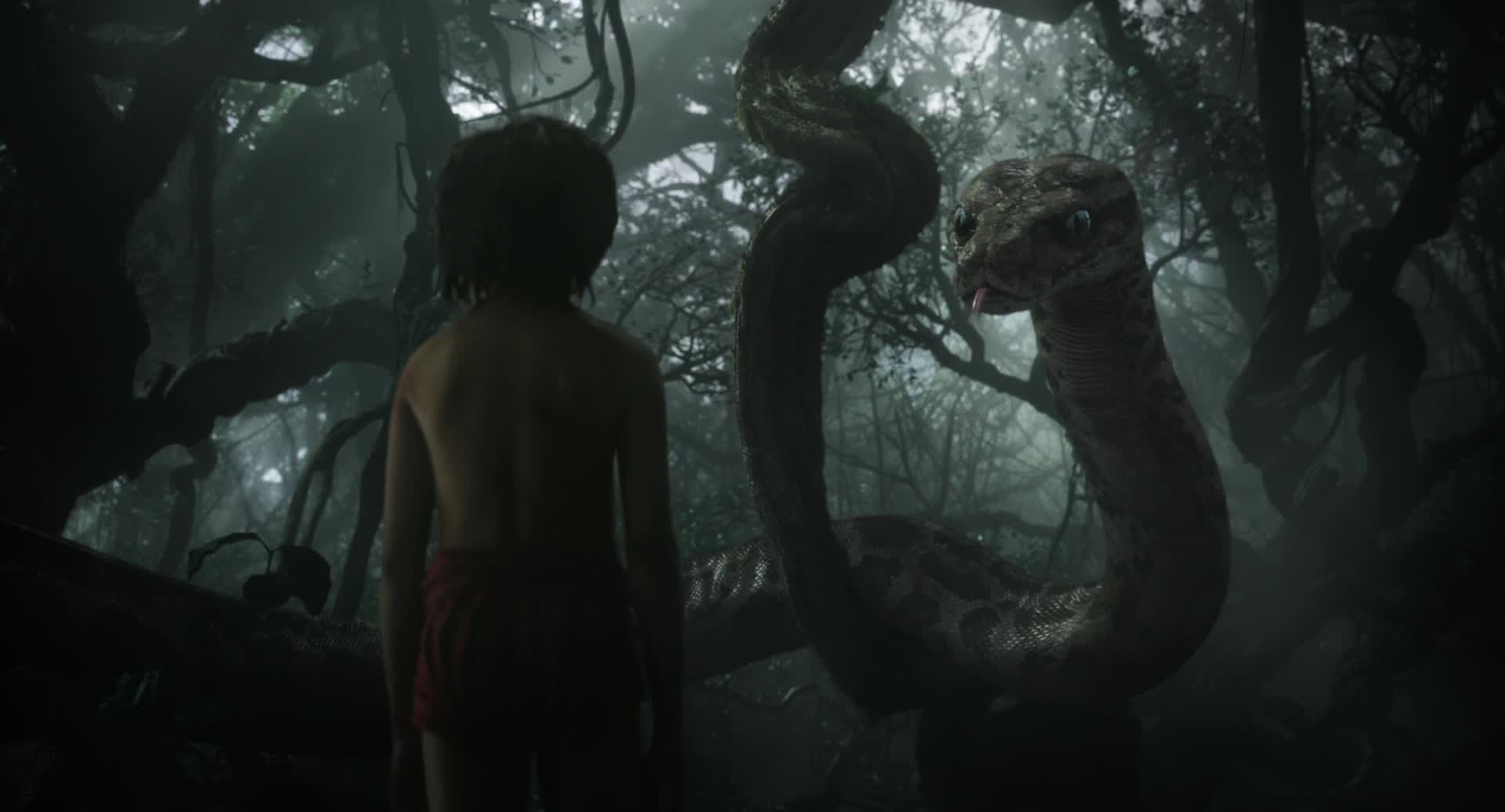

The Jungle Book inches ever closer to being an out-and-out remake of the 1967 film, the broad strokes between the two very much the same. In both films, Mowgli is found by a placid black jaguar named Bagheera in the jungle as a baby, and given to a pack of wolves to be raised. But one day, the specter of the fearsome tiger Shere Khan grows so great that Mowgli’s life is in danger if he isn’t shepherded to the nearby man-village. On this journey, Mowgli encounters a fun-loving bear named Baloo, a monkey king who wants to control fire, a hypnotic snake, and more. In the 1967 film, each of these episodic stops on the road trip are punctuated by songs, a few of which are among Disney’s most beloved: “Trust in Me,” “The Bare Necessities,” and “I Wanna Be Like You.” All of these songs are referenced, if not sung in part or full, during the live-action film. Kaa, as voiced by Scarlett Johansson, is much less a figure of comic relief, but we only hear her utter the words “Trust in me” in the film proper; in the lengthy end credits, Johansson—sounding a lot like Lana Del Rey herself—sings a low-key version of the song.

The latter two songs, sung by Baloo and King Louie, are such Disney highlights that it must have been hard for Favreau and Marks to avoid utilizing them. Both Bill Murray and Christopher Walken, who portray the characters in the new film, get to sing a verse of each of these songs in the actual film. (In the end credits, Walken sings a longer, more complete version of “I Wanna Be Like You.”) But this version of The Jungle Book isn’t really a musical, only incorporating those two songs in the movie, and barely quoting the George Bruns score from the original film in place of John Debney’s less memorable new compositions. A good chunk of the little details in this new Jungle Book are different from, and darker than, its predecessor. Mowgli’s separation from his adoptive mother, voiced by Nyong’o, is more moving than his leaving the wolfpack in the original film; Nyong’o invests a great deal of emotion in her brief screen time. Shere Khan is a much more terrifying baddie here; Idris Elba’s performance is superlatively evil, far surpassing the silky tones of George Sanders in the original. Though both films’ climaxes involve Mowgli and Shere Khan facing off in the middle of a fiery blaze, the details here—which make Mowgli a more active participant in the battle as opposed to sitting off to the side as Shere Khan and Baloo tussle—are enough to separate the live-action film from the animated one.

So many aspects of this new Jungle Book are different enough that the few scenes where the old music is incorporated feel shoehorned-in, a pointless way to placate diehard fans. The unfortunate result is that the various nods to the original film feel forced in ways that the new directions don’t. (So too do the minor bits of dialogue when the characters slip into the modern vernacular, as when a porcupine says “My bad.”) It’s easy to assume that a diehard Disney animation fan would be displeased with the final result of this Jungle Book no matter what, but the interesting thing is that Favreau’s take on the material might be the best of these live-action remakes yet, in no small part because of the visuals as well as the stacked cast not sleepwalking through familiar material. It’s at its worst when it halfheartedly tries to copy the original.

What Disney needs to do from this point forward is to either go all in on remaking its animated movies directly, or encourage filmmakers to go as far afield from the animated source material as possible. If you’re going to cannibalize your old content, swallow it down whole instead of hemming and hawing with having a few bites. We’re still four months away from the release of Pete’s Dragon, but even the brief teaser trailer suggests that David Lowery’s version will stray, to an extreme, from the 1977 live-action/animated hybrid. Next spring, Disney’s releasing a new version of Beauty and the Beast; what little we know—such as the suggestion that new songs may be showcased—suggests it will be the other extreme, utilizing a massively talented ensemble cast and director Bill Condon to create a live-action musical of the 1991 animated film. (As awful as it was, Tim Burton’s 2010 Alice in Wonderland chose to move a great deal away from the 1951 animated film.)

Maleficent, Cinderella, and The Jungle Book all want to retell famous stories, stories made partially more famous by Disney animation; they also want to honor those animated films. The truth is that the more that filmmakers go out of their way to pay tribute to the films that inspired the ones they’re making, the more it makes the new movies too beholden to the past. Better are remakes that dare to boldly reimagine their predecessors: Think, for instance, of P.J. Hogan’s 2003 Peter Pan, which poignantly acknowledged the mature subtext in Peter and Wendy’s connection. If we have to accept the reality that Disney is going to make a lot more of these live-action remakes of animated films, then it’s time to hope that they can draw enough of a separation between the two. Let the animated and live-action films live separately. Let them be their own beasts.