Today marks 100 years since the release of D.W. Griffith’s Intolerance: Love’s Struggle Through the Ages. Just 19 months earlier, he’d had cinema’s first blockbuster smash hit with The Birth of a Nation, a film about the American Civil War and white supremacy’s defiant triumph over the forces of integration and social equality during Reconstruction. As it was setting box-office records around the country and generally being hailed as the greatest thing in the 20-year history of commercial motion pictures to date, Birth was also being heavily protested by groups outraged at its blatant racism, including the fledgling NAACP and its leader, W.E.B. DuBois; and activists like Jane Addams, who sought to have the film banned. It wasn’t, and its massive success persisted for decades, being used as a recruitment film by the Ku Klux Klan into the 1960s. Outraged by the calls for censorship as attacks on his artistic freedom, Griffith quickly produced a pamphlet titled The Rise and Fall of Free Speech in America, and retooled a feature he’d been working on before Birth into one part of what would become a massive film of four stories, taking place in four different time periods, unified by the theme of intolerance. By that, he meant the hypocrisies of a liberal progressivism that called for freedom and equality yet had no problem pressuring the government to suppress his film. Occasionally and erroneously claimed to be a kind of apology for the racism of Birth of a Nation, Intolerance is, in fact, Griffith’s vehement defense of his constitutional right to be racist.

Or, it would be if the film managed to hang together thematically. Really only one of the four stories is about intolerance, though Griffith would go to heroic efforts to twist the narratives to fit the title. The longest section, set in the present, was the one already underway. It’s about a young couple struggling to survive in the big city in the wake of a destructive strike that forced them to leave their factory town. The man falls in with gangsters and ends up in jail. The couple are reunited only to have the man be taken away for a murder he didn’t commit. Turns out, the ultimate cause of their woes is an auxiliary of social-justice-warring women. First, they pressure the factory owner into over-funding their campaigns, which causes him to slash his workers’ wages, leading to the bloody strike, thus forcing The Boy (Robert Harron) and Mae Marsh’s The Little Dear One (generic names are a Griffith affectation: an attempt to make his specific characters universal types) to leave for the big city. Later, the women will steal The Little Dear One’s baby and place it in an orphanage on the flimsiest evidence of her motherly unfitness. Griffith’s most egregious stretch comes when The Boy is framed by his gangster boss for theft and put in prison, which the director calls the House of Intolerance, while a title card explains that he has been “intolerated away for a term.” The critique of the do-gooders is clear: It’s their moral hypocrisy that is so destructive. In striving to reform other people and not tolerating their vices (which amount to little more than liquor and dancing), they end up doing more harm than good. But Griffith doesn’t stop there: He actually implicates the criminal justice system as the agent of intolerance, apparently arguing that society should be more lenient toward murder and theft. While there are legitimate critiques of the carceral state, somehow I don’t think D.W. Griffith intended to suggest that the American prison system should be abolished altogether, as the film’s simplistic duality seems to propose.

The connection of intolerance to the smaller two sections is more tenuous, but still somewhat comprehensible. The shortest of the film’s four storylines is an extremely truncated Passion story, briefly relating the Wedding at Cana and the story of the Woman Taken in Adultery, and later incorporating images of Golgotha and the Crucifixion into the film’s final montage. In omitting any of the other aspects of the life of Jesus (the Sermon on the Mount, the attack on the moneylenders at the Temple, the Last Supper and betrayal by Judas, etc.), Griffith is specifically linking the story to the Modern section—the wedding as an indictment of the women’s anti-alcohol stance, the adultery as a rebuke to their general hypocrisy: “let anyone among you who is without sin cast the first stone.” That’s coherent and unobjectionable, but because he must stay consistent with his structuring conceit, Griffith must also make this a story of Love’s Struggle Against Intolerance, which means that there must be an identified agent opposed to Jesus. Thus, Griffith blames the Pharisees and positions them as responsible for the Crucifixion. This is barely dramatized, but it appears that the reason for this isn’t so much that they’re intolerant of Jesus, but rather that they see him as a threat to the social order they represent.

This kind of religious power politics is the true origin of the conflict in the next story, that of the St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre in France in 1572. The killing of masses of Calvinist Huguenots by Catholic mobs instigated by Catherine de Medici and the French crown in the midst of the Protestant Reformation certainly had something to do with religious intolerance; more important in reality, though, was a nexus of political and economic tensions underlying the complex French aristocratic system. Griffith nods at the vast array of figures that played a role in the lead-up to the massacre, but devotes almost no time to exploring the complexities of the history (a section on the attempted assassination of Huguenot Admiral Coligny was cut out of the final film). Instead, he focuses on a love triangle, with a very young Eugene Pallette as a Huguenot in love with a woman known only as Brown Eyes (Margery Wilson), who is in turn lusted after by a Catholic mercenary. There is no religious rationale given for the conflict, no expressions of hypocrisy (as in the Modern story) or ideology (as in the Passion story). Rather, the nobles are cruel and bloodthirsty, and our love triangle is merely a small human story caught in the incomprehensible movement of history.

The film’s last section is its biggest in scale, but also the one that least fits the theme. Set in 539 BCE, it chronicles the Fall of Babylon as it was conquered by the Persian Empire. Mangling the history, Griffith suggests that the Neo-Babylonian Empire (a remnant state of the disintegrating Assyrian Empire) under Prince Belshazzar was a paradise of religious freedom, a height of human civilization which the Persian invasion would bring to an apocalyptic end. In fact, the Persian Empire was noted for its tolerance, certainly compared to the brutal Assyrians (of whom Belshazzar and his father King Nabonidas seem to be particularly unwarlike examples: Griffith correctly notes Nabonidas’s fondness for archeology), and Babylonian civilization would survive for several more centuries after its absorption by Cyrus the Great, the honorific by which the Emperor is known throughout history but which Griffith denies him. Indeed, the Persian conquest triggered the release of the Jews from exile in Babylon, where they had been in captivity since Nebuchadnezzar II conquered Jerusalem and destroyed the first Temple in 587. Still, Griffith has a theme to maintain, and his version of the Fall is precipitated by the priests of Bel-Marduk, jealous at Belshazzar’s romance with a follower of the love goddess Ishtar. (This appears to be all Griffith: There was religious strife in Babylon at the time, but it was over Nabonidas’s preference for the moon god Sin. It simply wouldn’t do for a moralist like Griffith, though, to have his heroes worshipping Sin.) The Mardukian priests conspire to sneak the Persians into the city, leading to a great slaughter. We see most of this through the perspective of a young Mountain Girl, played in the film by Constance Talmadge. Independent and hilarious, she wears onions on her belt (it was the style at the time) and violently refuses to be sold in a marriage auction. She’s wooed by a handsome young singer, but ignores him in favor of her crush, Belshazzar himself. She fights alongside the men at the first Persian siege and races back to the city to warn the Babylonians of the oncoming final attack. She doesn’t tolerate nonsense and lives and dies gloriously.

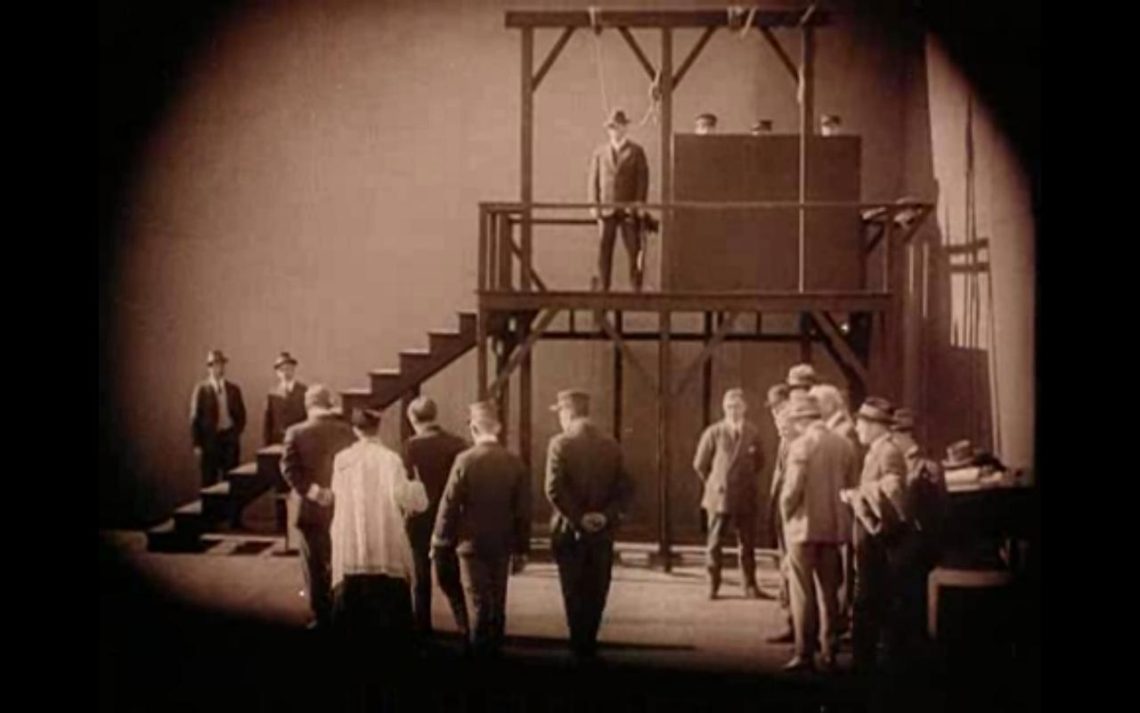

With its haphazard plotting and the failure of its stories to come together thematically, Griffith’s film decidedly fails as a political argument. And yet, Intolerance is nevertheless magnificent, the cinema’s first masterpiece of lunatic ambition. Griffith certainly didn’t invent the feature film, but The Birth of a Nation was nonetheless remarkable for its length and scope for 1915, and Intolerance topped it less than two years later. Its scale was rarely matched over the next 30 years (Fritz Lang’s Metropolis and Die Nibelungen, Abel Gance’s Napoleon, and Sergei Eisenstein’s Alexander Nevsky are a few which come close). In 1914, Griffith’s four-reel Judith of Bethulia told a story of war in the ancient Middle East, and looked like it was filmed in a dusty backlot with walls of cardboard. Two years later, the massive recreation of Babylon looks like it comes from another world entirely—a massive set packed with the coordinated movements of hundreds of extras, captured with a new technology: the crane shot (future director Allan Dwan claimed credit for figuring out how to capture it, by putting the camera on an elevator on a railroad track). The French scenes are more cramped, but just as ornate in their architecture, evoking a world of wealth and claustrophobia. The Modern sets are less fabulous, but no less perfect: their drab simplicity expressing the simple blandness of tenement life as Griffith saw it, with abstractions like the vast emptiness of the financier’s office, the stark lines of the gallows and the white abyss of the orphanage playing off the organic, lived-in dilapidation of The Little Dear One’s tiny apartment.

Intolerance, of course, was a milestone in the history of editing. While Griffith’s role as an innovator has been somewhat overstated by the desire to simplify history into a succession of firsts (first use of the close-up, first use of parallel editing, first feature film, etc.), his influence as the director who most effectively integrated all the techniques developed over the first decades of cinema into a popular mass form that foretold classical Hollywood style is undeniable. Intolerance represents his greatest experiment in parallel editing, cutting from one location in time and space to another and trusting that the audience wouldn’t get lost along the way. Freely moving from one timeline to another, Griffith used a variety of methods to cushion the radical effects of his montage, including explanatory title cards and a recurring image of Lillian Gish rocking a cradle as a transitional image, accompanied by variations on a line from Walt Whitman’s “Out of the Cradle Endlessly Rocking”—a vast and mysterious poem that contains depths Griffith’s film can only hint at. While the film served as an inspiration to Soviet montage theorists, Griffith was less interested than Eisenstein in conveying complex ideas than in simply comparing and contrasting. His cutting is more musical, fugue-like variations and repetitions reverberating throughout history, calling forth an overwhelming vision not of the forces of Intolerance, but rather of the struggles of the powerless against the impersonal movements of time.

When Griffith attempts to force the film into his chosen theme, Intolerance can be goofy and incomprehensible, because what is most moving in it has nothing to do with the director’s ideological polemic. Truth is, Griffith was a great director of emotions, perhaps the greatest, who nonetheless thought he was a director of ideas. This is why his best political film remains 1909’s A Corner in Wheat, where the simplicity of his argument by comparison is mitigated by the film’s brief running time. For the rest of his career, whenever Griffith would try to make a grand political argument, his technique and erudition would fail him, leading at best to naive simplicity and at worst to the vile excesses of his Klan hagiography.

But in Intolerance, all the sloppiness falls away beneath the power of his images, the rawness of the performances, the awe-inspiring scope of his ambition. Eugene Pallette, one of the great comic supporting actors of the ’30s and ’40s, as the embodiment of anguish when he discovers his murdered fiancée; Constance Talmadge’s utterly modern take on an ancient woman, all side-eyed and defiant, firing arrows at her enemies and leaping with joy when she hits her target; Miriam Cooper running away with the final third of the Modern Story, her haunted murderess, the Friendless One, barely holding her sanity together as she struggles between guilt and self-preservation. Every element of Griffith’s cinema is bent toward the emotional moment, his climactic sequences building, tragedy after tragedy, chase upon chance, to one final moment not of triumph but of ecstatic escape. The chase in the Modern section, a car racing after a train (anticipating The French Connection by 60 years), is the ultimate refinement of a formula he’d been perfecting since his earliest single-reel films, while the desperation of Brown Eyes trapped in an enclosed space calls back to early films like The Lonedale Operator or An Unseen Enemy (this situation would find its own apotheosis in 1919 with Broken Blossoms). While he is credited with popularizing many of the elements of continuity editing, in Intolerance he repeatedly violates the yet-to-be-established classical norms. Spatial and lighting continuity is ignored, as Griffith, when necessary, cuts to a dramatically lit close-up of one of his leading ladies simply because the emotional expression of the scene demands a close shot. He continually cuts across space, as one character thinks of another, but the perspective is never altered: We don’t see The Little Dear One’s vision of The Boy in prison, but an objective cut to him, as if the characters were clairvoyant. He makes liberal use of the iris, not just to create a portraiture effect around his leading ladies, or as a pseudo-spotlight to highlight the important part of the frame, but to reformat the filmic image into a cinemascope-shaped horizontal band, or a pillar-boxed column. His camera pans and tracks and moves in for extreme close-ups, obliterating the presentational prosceniums of his great European contemporaries Louis Feuillade and Victor Sjöström.

This spatial freedom finds its match in the temporal structure of the film, bending chronology to fit a larger dramatic narrative. There are several rhymes between parts of each of the stories, as events in one find their parallel, echo or inversion in another. But there could have been more. In one of the scenes included in The Fall of Babylon, a re-edited version of the sequence Griffith later released as a stand-alone feature, the Mountain Girl imitates the fashionable ladies’ walk in a scene that directly recalls one from the Modern story. The aforementioned echoes of the Wedding at Cana with the Temperance crusade of the women’s league did make the final cut, and was repeated in the standalone version of the Modern section, The Mother and the Law. A more rigorous filmmaker would have woven more rhymes into the structure of the film, increased the interconnections, balancing the sections and tying everything together in a neater package (as the Wachowskis did in Cloud Atlas and “Sense8”). It would have been more perfect, but not necessarily better. Intolerance is the first magnificent failure in film history, the first film to push the form beyond what the audience would accept, the forerunner of Greed, The Idiot, Heaven’s Gate, Southland Tales. These are films that reach beyond what they’re capable of achieving—not just technically, but personally. In not quite achieving the perfection they strive for, they draw us into their lunatic quest. Like those films, Intolerance was a financial failure, and Griffith never really did anything so ambitious again. There would be a spectacular sequence here and there—the ice-floe climax of Way Down East, the battle scenes in America and Hearts of the World—but his greatest later successes were on a much smaller scale: the lonely tragedy of Broken Blossoms, the bittersweet struggles of Isn’t Life Wonderful, the devastating romance of True Heart Susie. These films are Griffith’s best work, but Intolerance, for all its imperfections, remains his most glorious.