Spike Lee is one of the few directors working today whose style is immediately recognizable. From the tone-setting opening credits sequences, to the famously infamous double dolly shot, to cinematography and editing that felt as if it were physically affecting you in the theater, Lee’s films more than earn that unique opening credit “A Spike Lee Joint.”

When She’s Gotta Have It hit theaters in 1986, critics called Lee “the Black Woody Allen.” 27 years and 20+ movies later, I still don’t understand the color-coded calculus of that statement. Perhaps the critics were psychic, and knew Lee would, like Allen, become a quintessential New York City director. But they were wrong if they based their assessment on Lee’s potential to stay in the romantic comedy genre to which his first feature belonged. Instead, Lee exploded in all directions, shooting powerful documentaries like 4 Little Girls, crime dramas like Clockers, and nostalgic remembrances like Crooklyn.

Lee began bucking predictability with his second feature, the fabulous, brilliant and flawed hot mess, School Daze. Over the years, I’ve become fiercely protective of that film. If his third feature—and his masterpiece—Do the Right Thing made him a cinematic superhero, School Daze is his origin story: It’s a great encapsulation of the best and worst characteristics of Lee’s work. Like all his films, it has social commentary, satire, great cinematography, comedy, drama, a fearless take on ethnicity, and a musical-style nimbleness behind the camera. It also has the lousy dialogue and overlong rambling nature that occasionally proves that the screenwriter version of Lee can be the director’s own worst enemy.

Lee embraces his influences, weaving them into his style and visually name-checking them where necessary. There’s more than a little Scorsese in Clockers, and not because Scorsese was the producer. The love for Network makes Bamboozled almost an homage to Chayevsky and Lumet. You can find the stylish flourishes of Vincente Minelli in the zoot suit sequence of Malcolm X. And so on; there’s cinema history nesting inside the funky, contemporary and urban vibes emanating from Lee’s films.

Spike Lee surfed in on “the Black New Wave” and while that Hollywood-coined phase has come, gone, and seemingly come back again, he has never left the water. He’s transcended being “that Black director” to become one of the great American directors. In honor of Oldboy, his first remake, the writers at Movie Mezzanine take a look back at Lee’s joints. – Odie Henderson

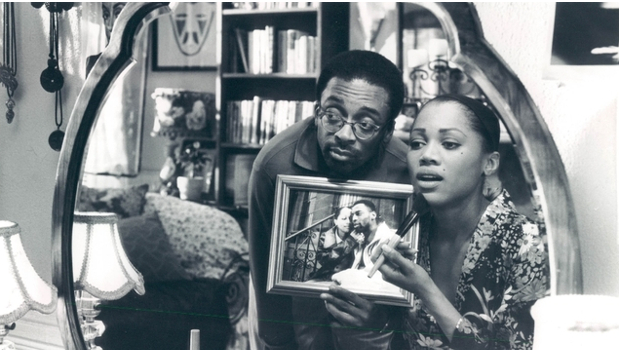

‘She’s Gotta Have It’ (1986)

(Grade: B+)

Mr. Lee’s debut feature film, for all of its dated fashion and visuals, still feels so richly and authentically *new.* It depicts a world we still rarely ever see on a big screen, and it tackles a subject — the sexuality of a contemporary black woman — that is rarer still. Historically, She’s Gotta Have It is a game-changer for its depiction of African-American life on screen, granting a complexity and a soul to its main character, Nola Darling, and satirizing gender roles and sexual dynamic with incredible sure-handedness considering this is a first feature. It has some flaws in execution, and certainly the ultimate conclusion of a controversial Nola-Jamie encounter is a less-than-ideal turn of events (Lee has said publicly he would change the scene if he could), but it’s hard to deny the appeal of the film, the newness of the subject, and the boldness of Lee’s introduction of himself to the world. – Russell Hainline

‘School Daze’ (1988)

(Grade: A-)

She’s Gotta Have It bustles with the restless energy of a great debut film, but School Daze is the picture where Spike Lee defined himself as an artist. Color photography and a larger budget allowed him to reveal what he’s almost always been interested in doing: re-claiming Hollywood stereotypes, genres, and aesthetic tropes, and using them to talk about the African-American experience.

“Daze” dramatizes the many conflicts that occur at a Morehouse-style college named Mission, where the lighter-skinned students (“wannabes,” colloquially,) and their darker-skinned peers (“jiggaboos”) find themselves in constant conflict. Lee shoots the loosely structured narrative with a Technicolor sheen and virtuoso camera movements, allowing a pleasurable kineticism to infect every sequence (there is one fully choreographed song-and-dance number). It creates stunning dissonance; the rawness and specificity of the social rifts intermingling with the musicality of the more artificial elements. His first picture suggested he could be an underground sensation – School Daze showed that Spike, in his own way, spoke the language of classical cinema. – Jake Mulligan

‘Do the Right Thing’ (1989)

(Grade: A+)

One of two masterpieces from Mr. Lee, he creates a world that feels like home. I know these people. How critics upon its release focused upon the anger and the racial politics instead of the astoundingly resonant depiction of dozens of unique individuals is beyond my personal comprehension. Mookie. Sal. Radio Raheem. Buggin’ Out. Sweet Dick Willy. Mister Senor Love Daddy. Smiley. My personal favorites, Da Mayor and Mother Sisters, whose final scene together reduces me to tears every time. I could go on. These aren’t characters — I can’t call them characters. They’re people. The battle between love and hate rages eternally. In Do The Right Thing, I find so many reasons to love. – Hainline

‘Mo’ Better Blues’ (1990)

Grade: B-

Mo’ Better Blues asks us whether the popular is worth anything if the radical doesn’t exist. With Bleek Gilliam creating music that he finds interesting to himself while at the same time romantically gambling with the women of his life we’re left just to watch all the chips fall and wonder why it had to be this way. Lee makes a well structured cyclical tale of ambition and obsession, whether one impedes the other or if it’s actually an evolution. All at the same time making the culture of Jazz and black music in the world of New York City be on center stage. What kind of music were you listening to in 1990? – Andrew Robinson

‘Jungle Fever’ (1991)

(Grade: A-)

If there’s one thing I adore about Spike Lee’s early films is that they always feel like a broad brush being painted to shine a light on issues he was seeing in his worlds. With Jungle Fever he gets to talk about the society’s current feelings on the topic of interracial relationships. Lee’s films, to an uninitiated and current viewer, may come off as overwrought with racial stereotypes and scenarios that we hope we’re all past in this current climate. However, they at the same time are nothing more than the cinematic equivalent of Spike Lee sitting and having a sincere discussion of what he felt was happening with him and his community from his sole perspective, which I refuse to ever ask him to apologize for. – Robinson

‘Malcolm X’ (1992)

(Grade: A+)

When I was teaching high school, I used to show Malcolm X to every one of my drama classes. The most amazing thing would happen every time: even the shortest attention span in the room would remain riveted for the duration of the film’s over-three-hour run time. How is this remotely possible? It could be Denzel Washington’s performance, one of the all-time greats in the history of cinema. It could be Ernest Dickerson’s lush cinematography or Terence Blanchard’s moving score. It could be that finding a film of this scope that doesn’t file down the subject’s sharp edges and staunchly refuses to patronize to its audience is as refreshing as it gets. I like to imagine it’s because they’ve never seen a biopic this good. In my nearly three decades of cinema-watching, neither have I. – Hainline

‘Crooklyn’ (1994)

(Grade: B+)

All of Spike Lee’s movie are ‘personal’, but many of the details that make up his growing-up-in-70s-Bed-Stuy picture Crooklyn are clearly autobiographical. Written by Lee himself, with two members of his family, the picture is littered with notes so specific that they could only come from personal experience. It’s a film full of neighborhood screaming matches, household battles over boxes of cereal, the perils caused by lost pets – those moments that seem minor but actually help to form a child’s, an artist’s, emerging view of the world.

The picture is one of the (relatively rare) low-key character studies in the Lee canon, and he’s as adept in this mode as he is with his more characteristically bombastic narratives. And the world he allows Woodward and Lindo to create – almost entirely in-between their lines of dialogue – remains one of the clearest illustrations that the auteur is one of our strongest actor’s directors. Crooklyn is so fully realized you can feel the steam coming off the sidewalk, smell the breakfast cooking on the stove, and feel the pain burning off of each character. – Mulligan

‘Clockers’ (1995)

(Grade: B+)

Six years after Do the Right Thing, Spike Lee returned to the genre he helped create, the so-called hood movie. Clockers put a grand, sad cap on the group of early 90’s films about urban youth (such as Straight Out of Brooklyn, Boyz N the Hood and Menace II Society) made by directors generally a decade younger than Lee. He and Richard Price adapted Price’s novel about low-level drug dealers in New Jersey, moving the action to a Brooklyn housing project. Martin Scorsese had been set to direct, with Robert DeNiro in the role of Detective Rocco, until both bounced to go make Casino.

The adaptation Price wrote for Scorsese gave Rocco roughly as much screen time as Strike, the ailing young drug dealer caught up in vicious street-level politics and a murder investigation. The Spike-Price rendition made Strike the lead character. Two inspired choices spun out of this decision: Discovering untried but magnetic Harlem teenager Mekhi Phifer for the role of Strike and hiring wildly experimental young cinematographer Malik Hassan Sayeed. Sayeed’s cocktail of varying film stocks (including Super-8 and super-saturated color reversal film), documentary grit (a scene of drug “clocking” shot as if from a narc’s surveillance van) and operatic flourishes (an interrogation room toplit in the exact blown-out style of Scorsese’s soon-to-be regular cameraman, Robert Richardson) puts us in Strike’s restless, distracted, yearning frame of mind.

The musical selections range from hyperkinetic rap to somber selections by Seal, Chaka Khan and Marc Dorsey (whose “People in Search of a Life” makes the film’s opening montage of crime scene photos one of the saddest credit sequences of all time). Harvey Keitel (as Rocco) John Turturro, Delroy Lindo and the amazing Thomas Jefferson Byrd were born to spit Price’s grimy, punchy dialogue. Their characters’ demands and threats help Clockers become a deeper appreciation of the pressures facing boys like Strike, who in mainstream movies were rarely granted a conscience, intelligence or a dream. – Steven Boone

‘Girl 6’ (1996)

(Grade: C-)

When an aspiring actress is turned off by the industry due to the treatment she receives in an audition turns to employment as a phone sex operator her life slowly skews away from reality such that she no longer seems to reside within it for much longer. With titillation and fantasy being focused so much in the realm of films it’s interesting to see it looked at in such a demeaning manner as this film does as it asks whether being a phone sex operator could be better for the soul than it would be to be in movies. As we see Girl 6 — she is never given a real character name — slowly not be able to tell reality from fantasy we are left asking if film does the same to it’s viewers and participants? – Andrew Robinson

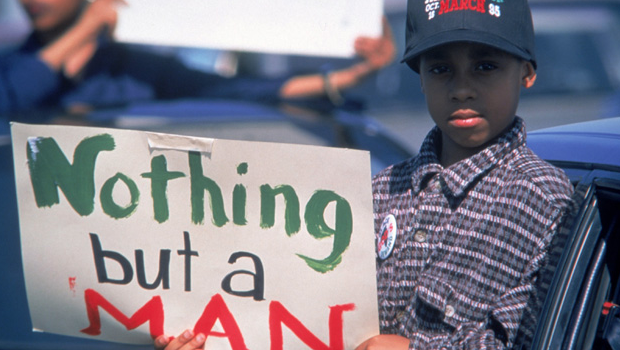

‘Get on the Bus’ (1996)

(Grade: B)

If one thing can be said about the one and only Spike Lee, it is that he is as form-pushing an auteur as we have from this generation. Be it big projects like the pending remake of Oldboy, or his various documentary pictures, very few directors have attempted to stay as experimental in their artistry as Lee. Look at a film like Get On The Bus. Ostensibly the story of 12 men sent entirely on a bus set to stop at the Million Man March, the film hints at the stage drama-type structure his dialogue has become known for (look at the play-likw banter in a film like Red Hook Summer), and also much of the stylistic choices Lee has been known to make with his camera. Often seen as a minor work in Lee’s canon, this dramatically resonant meditation on race is a powerful film that still holds up to this very day. A real gem of a film, led by a cast giving unanimously great performances. Must-see for those who haven’t, and worth a re-watch for those who have. – Josh Brunsting

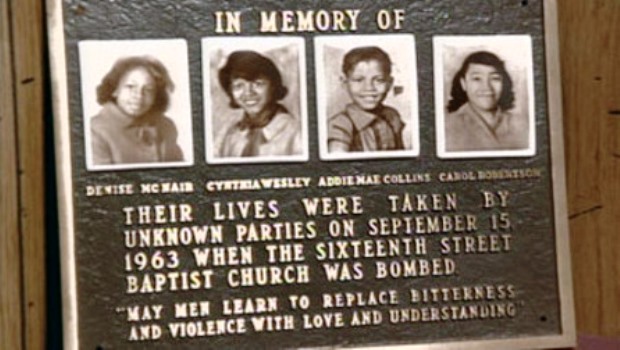

‘4 Little Girls’ (1997)

(Grade: A)

With 4 Little Girls, Spike Lee discovered his strengths as a documentarian. The film feels comprehensive in documenting the 1963 bombing of 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama. It takes the the time to make each of the girls killed in that terrorist act come to life as characters, purely through the testimony of friends and loved ones. Along the way, Spike even makes time for righteous mischief: A priceless scene of former Alabama Governor George Wallace, once so rabidly segregationist that he personally tried to block black children from entering schoolhouses, now testifying to his concern for black children and showing off a black assistant he calls his “best friend.” There’s some merciless irony in this film’s editing, completely in step with Lee’s dramatic features. The emotions are so carefully modulated that by the time we get to the bombings, and the awful images of what they did to those sweet little girls, it’s as if we were there that day. – Boone

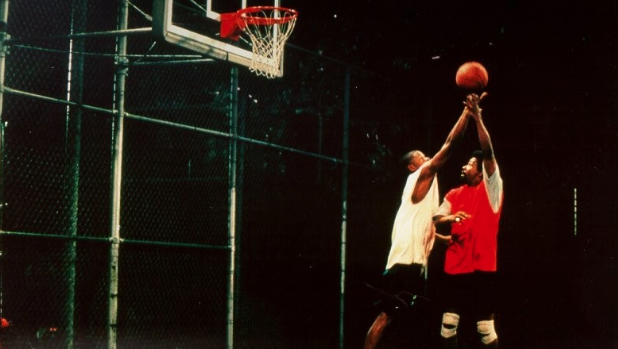

‘He Got Game’ (1998)

(Grade: B)

Basketball acts as religion in Spike Lee’s 1998 melodrama about a father and a son at odds with each other amid familial trauma. Lee’s real life passion towards the sport is well documented, but receives the holy treatment in this heavily flawed and passionate film. The setup is simple enough: A father (Denzel Washington) gets a free pass from jail in order to convince his superstar son (Ray Allen) to go to a college so he can earn a shorter prison sentence. The narrative is far from perfect as Lee’s diversions don’t quite add up, but the themes of redemption and forgiveness willfully linger throughout this overlong chorus of arresting sights and sounds (the film’s score comes from Aaron Copland). He Got Game may resemble an imperfect whole, but is worth seeing for a signature Denzel Washington performance. – Ty Landis

‘Summer of Sam’ (1999)

(Grade: A-)

The summer of 77′: Yankees took the world cup, disco fever blossomed, punk rock exploded. Bronx, like alll the NYC was sweating from record temperatures – and terror. In the heat of the night a psychopath, calling himself Son of Sam, was randomly killing innocent people in the streets. Lee paints a truly panoramic portait of the socio-historical moment with all its local, unique flavors. He skilfully infuses it with a deeper, psychological structure, focusing on his characters. A group of long-time friends is swamped by the killer related paranoia, their trust broken by fear and suspicion caused by a desperate need to put a face of the unnamed threat. Apart from great direction, Lee gave us an unforgettable soundtrack, delicious styling and rebellious screen energy, that is convincingly embraced by the actors. – Anna Tatarska

‘The Original Kings of Comedy’ (2000)

(Grade: A-)

People may know Lee best as a narrative fiction filmmaker, but let us not forget that he may be one of this generation’s greatest documentarians. Be it his work on a film like When The Levees Broke or his entrancing sports documentary, Kobe Doin’ Work, he’s as interesting a voice in the documentary world as he is in the fiction world. And this may be one of his best. Ostensibly a shot performance of a comedians Steve Harvey, D.L. Hughley, Bernie Mac and Cedric The Entertainer, the film is not only genuinely funny, but also very much a cultural touchstone. Near the top of the rather lengthy list of great concert documentaries, this is a style-heavy (especially with the gorgeous photography here) documentary that is both powerfully comedic and yet in many ways timeless. A triumph of documentary filmmaking from a voice routinely underrated in that universe. – Brunsting

‘Bamboozled’ (2000)

(Grade: A)

While much of Spike Lee’s canon has been devoted to the discussion of race and racism, very few of his films have ever been as angry, and yet breathlessly form-breaking as this unsung masterwork. Beautifully sardonic and brazenly uncompromising, this meditation on race as seen through the lens of popular culture is not only a great piece of modern satire, but a hell of a history lesson as well. By turning up the cultural stereotypes to their politically incorrect max, Lee is able to not only discuss the history of African-American portrayals in popular culture, but embeds an almost timeless sense of cultural vitality into the film. Stunningly shot in digital by the great Ellen Kuras (Coffee And Cigarettes), the film is a definitive Spike Lee picture not only in its themes, but in its aesthetic. With arguably one of his best double dolly shots adorning the opening of the film, this is, from frame one, as powerful and unforgettable a Spike Lee joint as we’ve seen from the director. – Brunsting

‘25th Hour’ (2002)

(Grade: A+)

As Spike Lee had done in the past and would continue to do so in the future, the peerless auteur bucked conventions with 25th Hour – creating the quintessential post-9/11 film that felt like nothing Lee had ever accomplished before.

Set to Terence Blanchard’s ineffably beautiful score, the film opens with images of the Tribute of Light. These blue beams remind us of the horror we’ve tried to endlessly erase from our memory, serving as the backdrop for the story of Montgomery Brogan. A once lucrative drug dealer who was busted by the DEA and sentenced to seven years in a state penitentiary.

With only 24 hours before he must report to prison, Monty does what many of us would us in do in such a situation. He says goodbye to those whom he needs to tell farewell, from his mournful father to his childhood friends. He spends time with his girlfriend. He eats a good meal. He contemplates his life, how he got here and what he could’ve done to avoid this predicament. He pronounces his regrets, ones that have irrevocably altered his life. Lee captures Brogan’s last remnants of freedom with equal amounts of penetrating pathos and delicate observations.

To see a man who, after today, will no longer be the same is a tragic experience. It’s hard to imagine sympathizing with someone who (in all likelihood) ruined the lives of many by distributing narcotics. And yet no matter how flawed he may be, Brogan (played by the always excellent Edward Norton) is an immediately likable figure. The ending comes and offers a glimpse of what could be. But the 25th Hour is more of an elegiac document of a human being than a hopeful one. I suppose the only optimistic note to be written here is that 25th Hour is not merely one of Lee’s greatest, most pensive and profound joints, but one of the greatest movies of the aughts. (For more, read David Ehrlich’s essential essay) – Sam Fragoso

‘She Hates Me’ (2004)

(Grade: B+)

She Hate Me sees Spike Lee, as usual, trying to pack way too much – too many ideas, too many narrative strands, too many themes – into one movie. That’s not a bad problem to have. This picture has, in no particular order: Woody Harrelson as an evil pharmaceutical CEO, Anthony Mackie impregnating almost 20 lesbians for $10,000 each (complete with animated sequences of sperm, with Mackie’s face superimposed on them, rushing toward digitized ovaries,) a plot that alludes equally to the federal whistleblowers of the early 2000s and historical figure Frank Wills, and an arguably-progressive love-triangle that intertwines Mackie, Kerry Washington, and her female lover; all of which is interspersed with commentary about the sexual commodification of the fit black male.

It’s loaded satire, but it’s also a reminder that Lee is, at heart, a moralist; obsessed with narratives about men trying to come to terms with the fucked-up world they’ve been born into, and the fucked-up people and standards they encounter every day. She Hate Me concludes with Mackey pleading his case to a panel of lawmen while a humongous audience cheers him on. Spike loves classical Hollywood – this is his kinky Frank Capra movie. – Mulligan

‘Inside Man’ (2006)

(Grade: B+)

This is the film that Spike Lee has been financially surviving on the for almost a decade now as it’s easily his most financially successful film ever. In the vain of Dog Day Afternoon we watch as a smart Detective takes on a smarter thief who uses distraction and supposition of others to pull off what we’re all to believe is the perfect heist. What makes this movie stick is how all these characters and ancillary threads all end up landing wonderfully, including that of Jodie Foster and Christopher Plummer, so as to keep adding flavor to what could have easily been a pretty tamer version of more classic films we all love already. – Robinson

‘Miracle at St. Anna’ (2008)

(Grade: B-)

Lee’s messes are far richer and more compelling than many filmmakers’ more tightly constructed narratives. Miracle At St. Anna has become something of a critical punching bag since its release, which baffles me. It’s a sprawling hopeful jumble of religion, race, war, and human nature, and while it has its lulls and its weaker moments, some of its stronger scenes are engrossing and haunting enough to elevate the rest. I’m a fan of Libatique’s beautiful cinematography, Blanchard’s predictably epic and sweeping score, and the performances across the board — in particular Laz Alonso’s, understated yet effectively carrying the film. Perhaps the miracle element rubbed some of the more cynical viewers the wrong way, or perhaps the film’s earnest heavy-handed execution disappointed those looking for a historical war epic with deeply religious overtones rooted in subtlety (*eye roll*). It doesn’t in the end meet the expectation that the phrase “Spike Lee Buffalo Soldier film” may plant into one’s brains, but there’s far more to like here than the masses generally give it credit for. – Hainline

‘Red Hook Summer’ (2012)

(Grade: C+)

The sixth film in Lee’s loosely-connected “Chronicles of Brooklyn” is a remarkably ambitious effort that unfortunately falters on the execution. The semi-autobiographical story follows Flik, a young man who goes to Red Hook to spend a summer with his grandfather, a preacher who goes by the name Da Good Bishop Enoch. It’s the rare film that tackles spiritual themes with honesty and humanism, acknowledging the paradoxes of religion and the messiness of believers while never feeling heavy-handed or manipulative.

How can the same faith that propelled the civil rights movement be used to keep minorities and the poor in check? Why are the churches that used to be community pillars slowly disappearing? Does belief in God inspire true change, or do good deeds actually stem from self-delusion? While Lee doesn’t reach any clear conclusions, the journey is invigorating.

Unfortunately, the low-budget aesthetic undermines its thematic weight. Clarke Peters’ powerhouse performance as Bishop Enoch is contrasted by the mediocre child actors around him. The first half meanders and flits from moment-to-moment with little connective tissue—it feels like jazz, but without the necessary confidence to pull it off. Red Hook Summer is a potent reminder that Lee still has worthwhile things to say and explore; let’s just hope that next time he sticks the landing. – Andrew Johnson

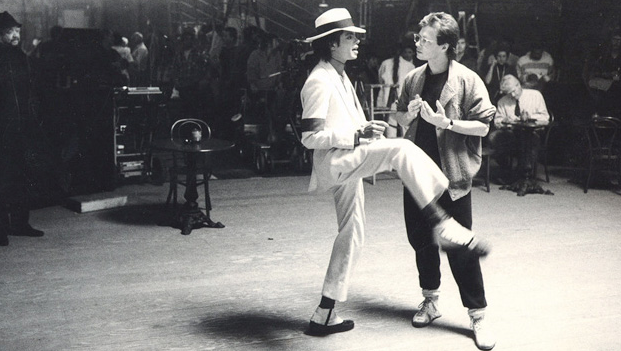

‘Bad 25’ (2012)

(Grade: B)

Some call it Lee’s “love letter” to late Michael Jackson’s artistic and cultural oeuvre. It seems like an accurate way to describe Bad 25. A real in-depth attempt to create a compete microcosm of the King of Pop’s world, the film is composed of over 40 interviews Lee conducted with Michael’s co-workers, friends and artistic heirs. This over two hours long doc is exciting and reveals Lee’s true passion and understanding of the subject. Jacksons multilayered personality, charismatic stage persona and, above all, his remarkable music, shine through. The film’s enthusiasm is as contagious as King of Pop’s tunes. – Tatarska

…

3 thoughts on “Examining The Films of Spike Lee”

I think he’s one of the best filmmakers working today. I could care less about what he says outside of his work yet he remains a very vital filmmaker. Even a bad movie from him is still better than most people’s films.

I agree with some of these (Bamboozled, 25th Hour, Do The Right Thing, Malcolm X) but alot of these grades are…generous. Two in particular stick out, Crooklyn and Clockers. In particular, Clockers is not a great movie, and not even that good. It has it’s moments but it’s more or less a mess.

A great summary but where is When the Levees Broke? Without doubt one of his finest achievements. An angry. passionate piece of filmmaking.