Don Hertzfeldt is, in my not-so-humble opinion, one of the most talented filmmakers working today. That statement may sound hyperbolic, but only until you consider that all of his movies are about stick figures, and that their combined lengths barely adds up to the running time of an average feature film. Then it sounds really hyperbolic. Despite this, I can think of no writer-director alive who demonstrates more ambition or obsessive commitment to his work, or who speaks in such a distinctive and (seemingly) personal voice. Hertzfeldt is truly one-of-a-kind: an auteur in the truest sense of the word, whose simple cartoons pose profound and sometimes frightening questions about life, love, and our place in an unpredictable universe, while at the same time using the ordinariness of human existence as a source of both great tragedy and enormous joy.

He’s also responsible for this:

The above is a moment from 2000’s Rejected, which is still probably Hertzfeldt’s most widely seen film, unless you count his deeply disturbing couch gag for a recent episode of The Simpsons. Often touted as one of the first-ever online viral videos, Hertzfeldt’s first film out of college helped establish him as one of the most unique figures in independent animation (it even got him an Oscar nod, marking the last time the Academy of Motion Pictures Arts and Sciences did anything genuinely interesting or unexpected).

Here’s the above clip again, in…I guess you’d call it context:

How, you may wonder, does this clip exemplify Hertzfeldt’s genius? For one thing, there’s the animation itself. The character’s face is so simple, yet incredibly expressive—the genuine, carefree happiness of the strange fluffy protagonist, suddenly replaced with shock and then terror as he realizes that yes, his anus is indeed bleeding. More to the point, in this 90-second scene of dancing and rectal hemorrhaging, we can see many of Hertzfeldt’s favorite techniques and recurrent themes on display: characters distracted by shallow delights, so malleable that they’re unable to see—or at least, are willing to ignore—the horror of what’s unfolding in front of them; a helpless hero, trapped by unfortunate circumstances that are at once absurd and yet weirdly mundane; a filmmaker whose sensibilities combine the surreal with the tragic, but who keeps himself grounded with a refreshing and unpretentious dose of morbid humor.

I can sense that you’re still skeptical. Let’s go back to the beginning, then.

AH, L’AMOUR (1995)

Hertzfeldt’s first widely available student film, made when he was just 18, isn’t exactly what you’d call a masterwork of animation. Indeed, it’s quite amazing to see how much he’s refined his technique over the last two decades, especially given that the core elements—hand-drawn stick figures brought to life frame by frame—remain more or less unchanged.

In terms of its content, Ah, L’Amour is a lot more simplistic than the films that would follow, yet Hertzfeldt’s voice is still unmistakable. The twisted gallows humor is there in spades, with the noose really tightening during the cheery yet oh-so-cynical denouement. Still, for my money, the most revealing moment in the film happens just after the 1-minute mark, when our lovelorn hero saunters right past the bucktooth woman in search of a more conventionally attractive date. Just like that, Hertzfeldt distinguishes the short as more than just a silly cartoon doodle, skewering the apparent thesis of his comedy (i.e. aren’t women just the worst?) with a single throwaway joke With our expectations and prejudices suddenly challenged, the rest of this freshman effort unfolds in a very different light.

GENRE (1996)

Hertzfeldt’s second student film is a brief meta-narrative about the relationship between an artist and his increasingly reluctant work of art. As amusing as Genre is, the ideas aren’t particularly new—in fact, it’s basically just a lo-fi adaptation of the classic Looney Tunes short Duck Amuck. It’s still interesting to note Hertzfeldt’s appreciation of genre conventions, especially since his later films seem to so readily defy such labels. Particularly apparent is the influence of silent comedy, which can also be seen in Ah, L’Amour and many of the films that follow. Be that as it may, Genre is easily the least remarkable entry in the Hertzfeldt canon.

LILY AND JIM (1997)

At first glance, Lily and Jim seems like an outlier: a dialogue-driven piece that swaps insanity for mundanity. Yet it’s also perhaps the most significant of Hertzfeldt’s film-school output in that it represents maturation in his use of comedy. Gone is the violent, mean-spirited humor of Ah, L’Amour and Genre, replaced by the more tragicomic tone of the filmmaker’s later work. Even when things take a turn for the grotesque after Jim’s unfortunate allergic reaction, the joke isn’t on him so much as it is on the excruciating awkwardness of his situation.

Cringe comedy isn’t easy to get right, but Hertzfeldt proves himself a natural. I particularly love the way the “camera” lingers on Jim way too long around the 80-second mark, and also the offhand line about his friend the economic analyst. But beneath the awkward humor lies that palpable feeling of loneliness. Lily and Jim are painfully relatable characters: well-meaning, but racked with insecurity and the fear of making the first move. Hertzfeldt’s greatest talent is the way he’s able to make us empathize with his crudely drawn characters. And while he’s aided immeasurably in this occasion by his voice actors, Lily and Jim is still perhaps the clearest signal from this era of the filmmaker he’d eventually become.

BILLY’S BALOON (1998)

It seems weird, having just praised Lily and Jim for its maturity and humanity, to then turn around and heap adulation on Billy’s Balloon. Nominated for the Short Film Palm d’Or, this sick, twisted tale about a homicidal helium balloon has more in common with Ah, L’Amour and Genre than it does with Lily and Jim, tipping its hat to the era of silent comedy, while seemingly taking great glee in the misfortune of its protagonist. At the same time, I’d argue that there’s far more to it than initially meets the eye.

In Hertzfeldt’s first two shorts, the humor is derived almost solely from violence. Though equally disturbing, Billy’s Balloon also contains elements of both absurdity and banality. The situation in the film is obviously ridiculous, but unfolds in an incredibly matter-of-fact way, complete with static “camera” and absence of music. Despite its physical impossibilities, the violence feels real, something that’s driven home by Billy’s startled expressions. Indeed, of all the Hertzfeldt characters we’ve talked about so far, Billy’s face is easily the most expressive.

There’s also the fact that no one comes to his aid, and that the passing (faceless) adults are oblivious to the balloon’s sadistic intent. Billy’s utter helplessness makes the short feel that much darker, and not in a way that’s necessarily funny.

REJECTED (2000)

And so we arrive back at Rejected. Highly experimental, it’s easy to see why the film has enjoyed such a strong cult following on the Internet, where there seems to be a direct correlation between randomness and what’s considered funny. But while Rejected is definitely bizarre, it’s also arguably the first of Hertzfeldt’s shorts that’s explicitly “about something,” reflecting the filmmaker’s strong anti-corporate, anti-conformist philosophy. His take on advertising is particularly scathing: absurd, violent drivel with elevator music playing in the background.

I don’t put Rejected on the same high pedestal I do the two shorts that precede it. Its intentionally chaotic structure means there’s never really a chance for the film to connect on an emotional level; plus, I just don’t find it quite as funny (aside from the No Silly Hats bit, which is just gold). Still, it’s definitely a significant work, a major turning point in Hertzfeldt’s career. More than any film he had yet made, Rejected demonstrates Hertzfeldt’s willingness to a) disregard convention, b) risk alienating his audience, and c) be formally and intellectually ambitious—all while remaining self-aware. It’s this combination of qualities that really makes his later films stand apart.

THE MEANING OF LIFE (2005)

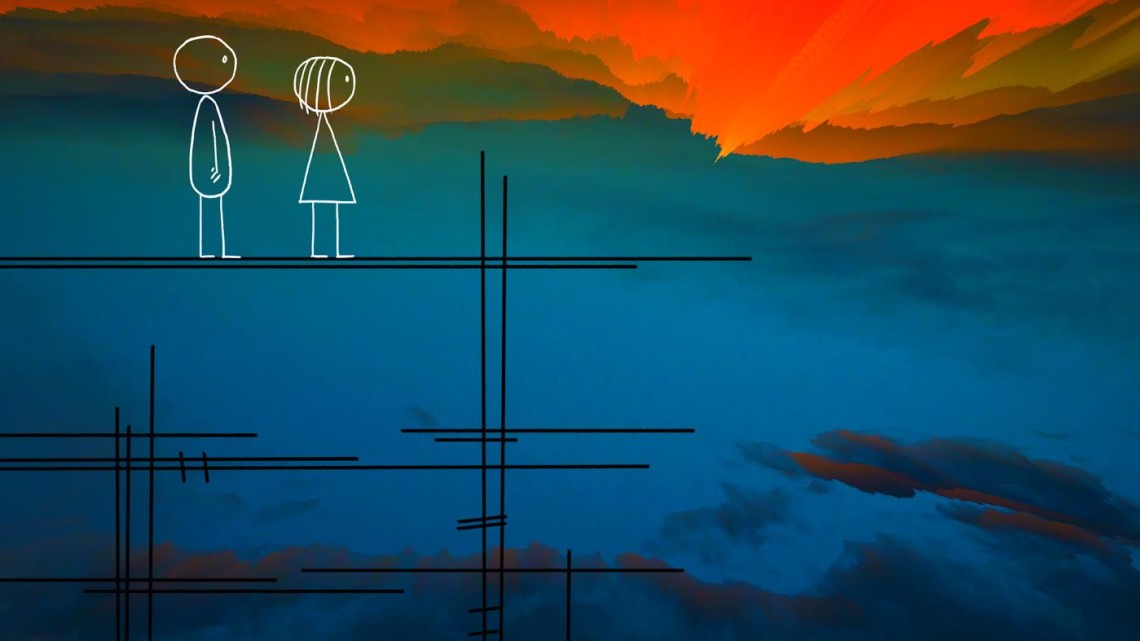

If Rejected marks the turning point in Hertzfeldt’s narrative ambitions, The Meaning of Life marks the turning point in his aesthetic. Indeed, from the moment the film begins, it’s clear that this is the work of a very different filmmaker, one whose influences seem closer to Stanley Kubrick and Terrence Malick than Mike Judge or Monty Python. While still only 12 minutes long, this is undoubtedly Hertzfeldt’s first epic, its temporal scope calling to mind a film like The Tree of Life, albeit with more bleating two-headed rage monsters.

The Meaning of Life is the first of Hertzfeldt’s films to make you appreciate the enormity of the job the director sets for himself. This isn’t the product of a team of animators; rather, it’s one man, drawing every frame by hand—which makes the film’s unexpected cosmic waltz segment that much more incredible. The fact that Hertzfeldt managed to pull that sequence off using in-camera effects remains as mind-blowing as ever (it’s clearly something he’s proud of, as evidenced by the disclaimer at the end of the credits).

While it might be slightly overshadowed by the animation, content-wise, The Meaning of Life might actually be Hertzfeldt’s grimmest film. It’s harder to think of a more depressing indictment of the human race than the one we’re presented with here: a mob of mindless, catch-phrase-spouting drones with no interest in anybody other than themselves. Even worse is that, even after another few million evolutionary steps, the situation doesn’t appear to get any better.

EVERYTHING WILL BE OK + I AM SO PROUD OF YOU + IT’S SUCH A BEAUTIFUL DAY (2006 – 2012)

Here it is: Hertzfeldt’s artistic summit. Originally released as three 20-minute shorts before being edited together and released as a single feature, It’s Such a Beautiful Day is nothing short of a masterpiece. Through his lead character, Bill, a man plagued by illness and misfortune, Hertzfeldt is able to explore questions of love, family, memory, and mortality, walking a tonal tightrope while pushing the boundaries of the medium further than he ever has before.

Indeed, while it’s easy to track Hertzfeldt’s progression through every one of his films, It’s Such a Beautiful Day feels like the true culmination of everything he has ever made, from the twisted dark comedy of Ah L’Amour to the surrealism of Rejected, the melancholy of Lily & Jim and the profound ambition and experimentation of The Meaning of Life. That it manages to be all of these things while remaining utterly unique is a better testament to Hertzfeldt’s brilliance than any combination of adjectives I can muster.

WISDOM TEETH (2009)

All right, so clearly Wisdom Teeth isn’t a masterpiece. Made between parts two and three of It’s Such a Beautiful Day, this film feels like a bit of a creative cleanse, in that it’s simple, grotesque, and intent on eschewing any sort of theme or greater point. Basically, for five-and-a-half minutes, we watch with increasing horror and bemusement as Nigel’s head is slowly, agonizingly unravelled. It’s gruesome and preposterous and a thousand times funnier for being in this made up Nordic language. There’s nothing deep about this film—but sometimes that’s just fine.

—

Hertzfeldt’s latest film, World of Tomorrow, is currently available on VOD.

5 thoughts on “Such a Beautiful Day: On The Works of Don Hertzfeldt”

Not to diminish it, but Rejected didn’t actually win the Oscar.

I really love Hertzfeldt now after reading this and watching all his shorts. Fantastic analysis all around. I had watched It’s Such a Beautiful Day on Netflix not long ago and was so taken off guard and blown away by it. Though I will say Wisdom Teeth was pretty dumb, and I pretty much hated Billy’s Balloon. I thought that one was just grim and morbid without really being funny and ironic. I’m going to rent World of Tomorrow ASAP.

Pingback: Film | Pearltrees

Pingback: Everybody’s Talkin’ 4 – 3 (Chatter from Other Bloggers) | The Matinee | Cinematic Passion & Perspective

Pingback: ‘World of Tomorrow’ solidifies Don Hertzfeldt as an auteur | Sound On Sight