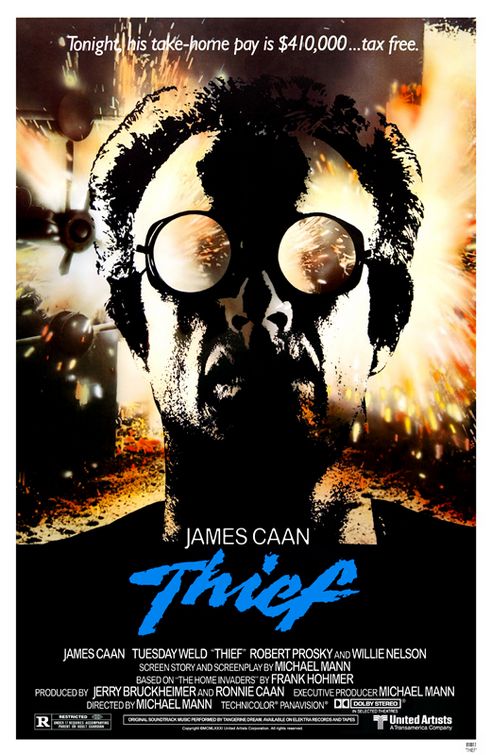

It doesn’t take an in-depth analysis of his films to figure out which themes Michael Mann has devoted his whole career to. He keeps his film titles simple, precise, usually one or two words: Thief, Manhunter, Heat, Collateral. Most of his posters feature men postured in grand ways. Read his films’ synopses and you’ll see that he has always had his mind on the worlds of crime, obsession, masculinity, America. Taken as a whole, his oeuvre could serve as a sprawling historical pictogram on the American male’s experience. This poster gallery is a way to follow this auteur’s career arc, how his precise, stylish voice and thematic obsessions became a singular force of American filmmaking.

Michael Mann’s first feature film Thief was not only the announcement of a singular American voice but would come to shape the modern crime thriller as we now know it (see Bilge Ebiri’s great in-depth analysis of the film’s influence here). Following Frank (a brilliantly hardboiled James Caan), an ex-convict released only 4 years prior, Thief puts the viewer into the head of a man who simply wants the American dream but who only knows the life of safecracking. And its one-sheet may very well be the best among his oeuvre. (Its effect is reflected in the way this poster’s style has been evoked in recent years, most notably for 2011’s Drive and 2014’s Nightcrawler.) With Frank front and center and his eye focused off frame in fixation on the prize, the poster roots the dynamism of Thief in Frank’s steadfast, precise vision. The sparks which consume his vision are from the machine which will open the final safe, leading to his dream coming true, yet this pursuit may very well set the whole thing ablaze.

Stepping away from the crime genre of his first and (subsequent) best films, Mann unleashed his sophomore effort, a WWII-era, supernatural horror film. With a most-80s of premises, The Keep throws Nazis, Jews, and ancient demons into a supernatural prison where they must combat the evil which lurks within. Viewers beware! I’m not sure if this is a thrilling box of campy schlock or if it is just plain awful. It could go either way. You’ll never know until you enter!

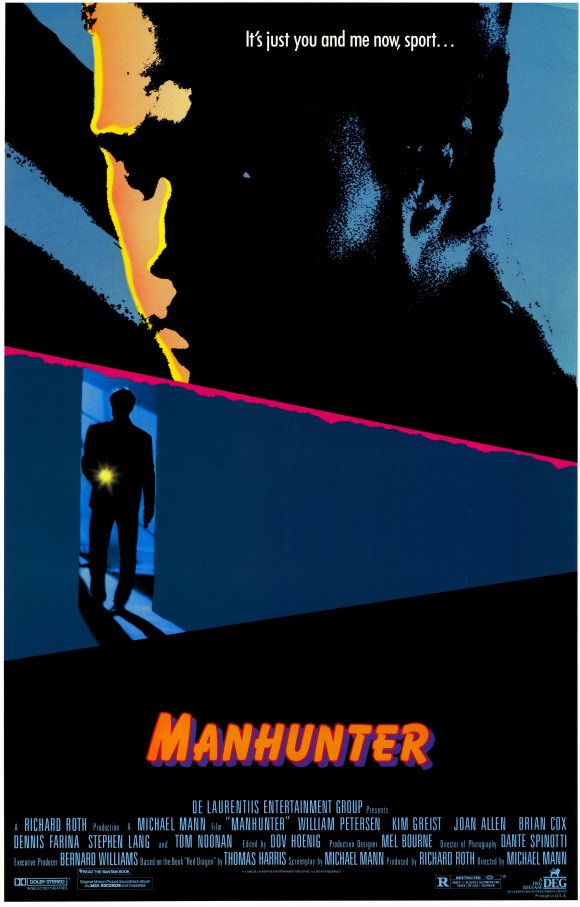

The first cinematic foray into Thomas Harris’ creepy, sadistic Hannibal Lecter series was Mann’s third feature Manhunter. Returning to genre form, this film follows former FBI profiler Will Graham as he’s called back into service to track down the serial killer “The Tooth Fairy”, helped along the way by the cannibalistic serial killer Dr. Lecter whom he imprisoned years earlier. The poster’s use of bold colors, deep blacks, and shadowed faces beautifully highlights Harris and Mann’s stark pulpy-noir dark thriller, the one-sheet itself a fractured tale about man’s dark search for evils well-hidden.

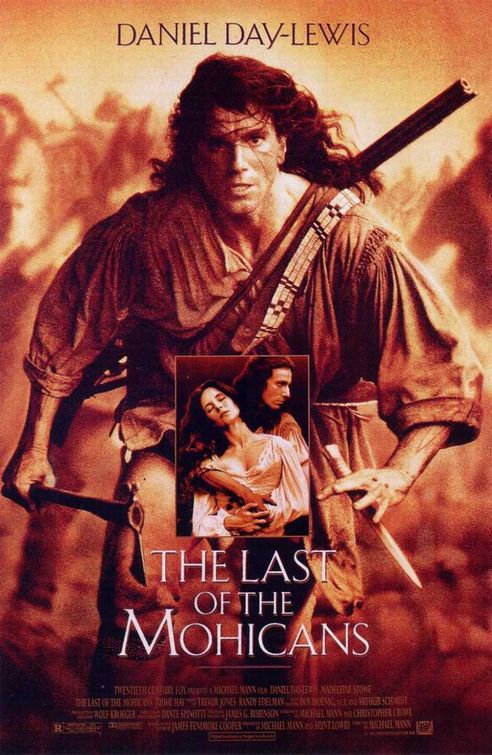

Early in his career, Mann was clearly not one to stay put within genre bounds. Thus, The Last of the Mohicans. The famous poster for this historical early-American war melodrama features a sepia-drenched Daniel Day-Lewis as Hawkeye running toward the viewer, tomahawk in hand, with the central romance between him and Madeleine Stowe’s Cora framed in poster’s center. (It is one of the the only Mann-posters featuring a woman.) Hawkeye is an Anglo adopted by a Mohican family who falls in love with the beautiful Cora, a daughter of a British officer. As the battles rage around them, their relationship transcends war as Hawkeye stops at nothing (see: said poster earlier) to save his love. With this melodrama Mann proved that he could successfully deal with a milieu apart from the crime world.

Pacino. Deniro. Kilmer. L.A. In Heat, all of the auteur’s elements are mixed to near perfection. This 1995 crime ensemble epic is a story about compromised, obsessive men, the high-precision of procedure both sides of the law, and the pursuit of a dream seemingly only a hair’s breadth away. Themes Mann has been exploring his whole career crystallize here on the L.A. pavement. Pacino and Deniro – the gods of the crime genre – face off in a cinematic chess match as police detective Lt. Vincent Hanna and master thief Neil McCauley, respectively. The poster depicts these two men and their company positioned in ways in which their perspectives are always just shy of what they are looking for, ever eluding one another. As pawns in Mann’s hand, they are used to tell the crime saga he has been working toward, his very own Godfather.

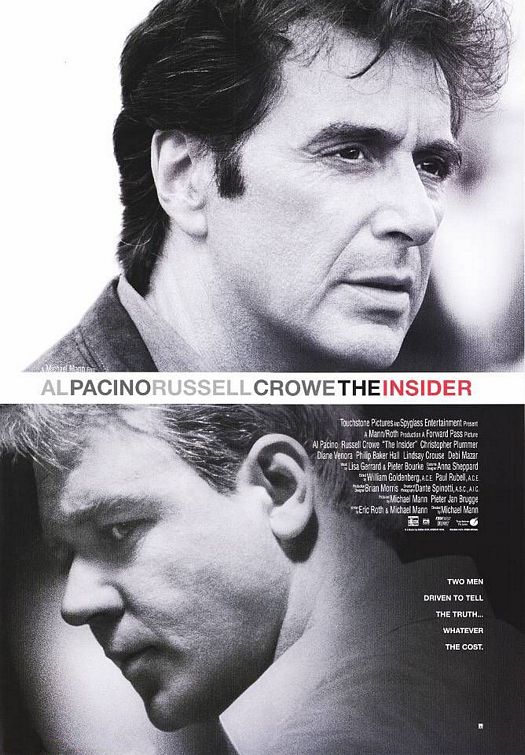

With The Insider, Mann again delivered one of the 90s best films. Based on a true story, this dramatic tale of shifting truth has Russell Crowe’s research chemist Jeff Wigand blowing the whistle on Big Tobacco in a “60 Minutes” interview orchestrated by Al Pacino’s TV producer Lowell Bergman. With these angered provocations, Mann crafted a seminal American work, revealing the corrupted rust of American capitalism’s machinations.

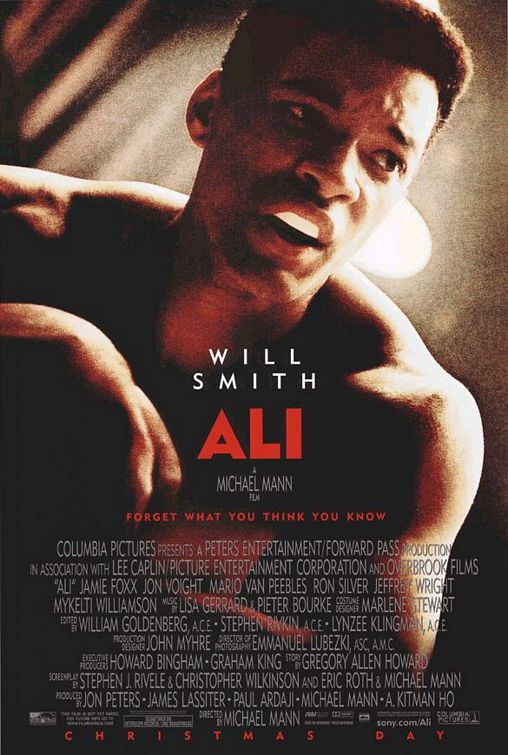

It is only fitting that one of America’s most successful directorial voices take on one of America’s most beloved heroes. In 2001, Mann delivered that film: a biopic of the world’s greatest boxer Muhammed Ali. Portrayed by the darling actor Will Smith, Mann creates a biography of a life in a specific time, following Ali from 1964 to 1974. Ali is the sprawling portrait of a man fighting his way through life’s ups and downs, an existential swinging for meaning in a world which never throws the same opponent in the ring.

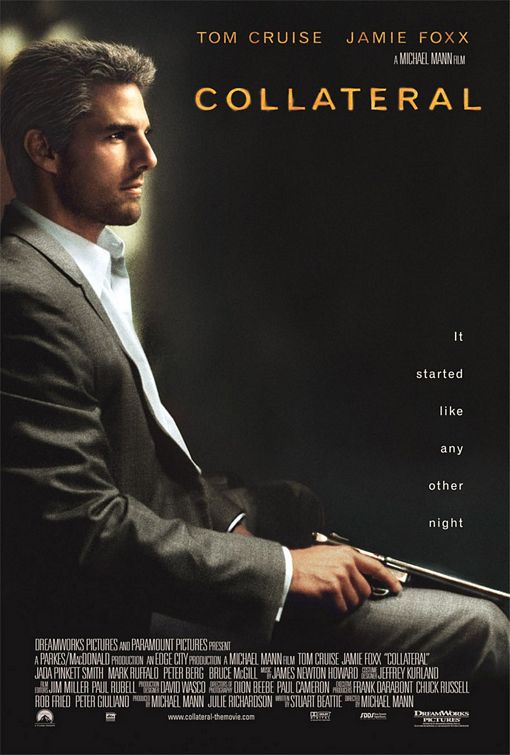

Returning back to his crime roots, Mann crafts another tense thriller set on the streets of L.A. With Collateral, he also manages to reenvision Tom Cruise into a villain, effectively playing him against decades of type. Cruise is the greyed, world-weary assassain Vincent who pays Jamie Foxx’s cabbie Max to drive him around all night. Little does Max know, Vincent is working. Mann again finds new, highly effective ways to explore his obsession of the criminal perspective by way of men who think of their evil-doing as vocation as they butt up against good men who must face the evil head on. This poster simply shows us a new Tom Cruise, with grey hair, sitting with gun in lap, waiting on something. He may just be merely waiting to be consumed by the darkness which inhabits the rest of the frame, only Mann knows.

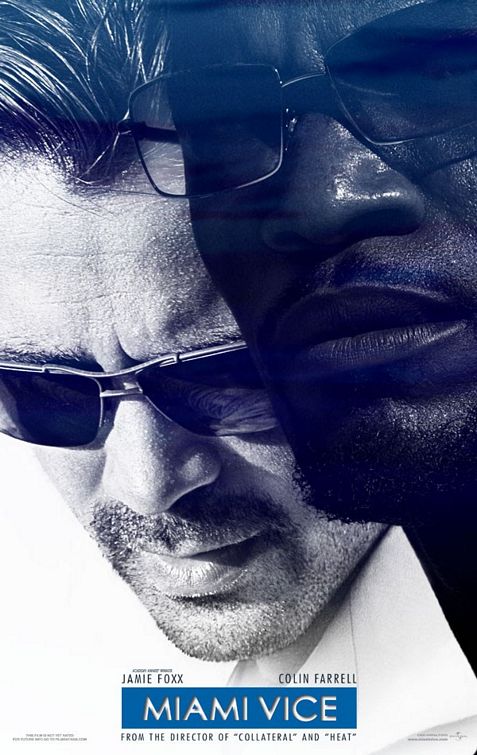

With its stark cocaine-white background, 2006’s Miami Vice teaser poster was Mann, who served as executive producer of the 80s cult TV series, boldly clearing the slate, refashioning a Vice for the early aughts. The unified star power of Farrell-Foxx invade the sheet, distancing this take from its roots, as Miami detectives Crockett and Tubbs are reincarnated into Mann’s highly stylized 21st century grit. With their heads exhaustedly bowed, this vice team seems weighed down by the doomed Miami underground which awaits them. This is not the world of Don Johnson and Philip Michael Thomas. Later posters would boast Mann’s mission statement for this new film, a tagline heralding the arrival of this modern Vice: “No Rules. No Law. No Order.”

By 2009, Mann has gone full-stalwart with a strong career crafting cinematic visions of America’s history, specifically the country’s most infamous battles from the male perspective. With the docudrama Public Enemies, he brings the story of John Dillinger and his gang to the screen. This film had him working with a set of new faces in Johnny Depp, Christian Bale, and Marion Cotillard, yet his career’s themes remain firmly in hand. A period piece set in 1930s Chicago, Mann reexamines a time when gangsters reigned openly as (mafia) kings and when the newly concevied FBI set out to destroy these empires. It’s another Mann-ish tale of procedure and vocation, watching two men’s (Depp’s Dillinger and Bale’s FBI agent Melvin Purvis) obsessive pursuits of the one on the other side of the dream.

It has been 6 years since Michael Mann’s last film, but he’s back in 2015 with Blackhat, a sprawling international thriller about, you guessed it, crime. But in eschewing the physical precision of his protagonists past, the dirty deeds are done in cyberworld this time. Blackhat concerns an ex-hacker convict (Chris Hemsworth) is released to assist in hunting down a high-level cybercrime network. With a new cast of players set in a modern world decades separated from his last film, Mann will find a way to make his voice heard in a new decade.