Abbas Kiarostami’s cinema was only discovered outside of Iran in the late 1980s, when Where is the Friend’s Home? (1987) was screened at the Locarno International Film Festival and won several awards. By then, the director had been active in the industry for nearly two decades and had become one of the most influential voices in Iranian cinema. Much of Kiarostami’s early output remains inaccessible. Thus, for casual observers of his work, the aforementioned film, with a young boy as its focal point, looks like an anomaly, after which the director became more preoccupied with formal experimentation and subtle treatments of heavy themes such as suicide, mortality, and spirituality. But Friend’s Home follows a rich trajectory of films by Kiarostami about children, which he produced at Kanoon, the Iranian Centre for the Intellectual Development of Children and Young Adults.

Kiarostami was one of the first directors to be associated with Kanoon, an institution that later produced and distributed masterworks by directors like Amir Naderi and Bahram Beizai, among others. Kiarostami’s films at the centre can generally be categorized into two groups: educational films made for children, and narrative films made about children, in which the director’s authorial voice is evident and evolves over the years. Several of these films center on young boys thrown into the adult world at an early age, facing challenges that are beyond their years. In these stories, reality often becomes a punishing revelation for the boys. The characteristic and thematic similarities that connect these films form a group of child protagonists, all belonging to the same universe—even if temporally and geographically, they are distinct.

Although the director’s 10-minute debut Bread and Alley is perhaps the earliest example of his archetypal protagonists, The Experience (1973) is his first longer film (60 minutes) to follow this narrative pattern. Kiarostami co-wrote the screenplay with Naderi, whose contribution to the story is autobiographical. The film’s young hero, Mammad (Hossein Yarmohammadi), is an orphaned boy who works as an assistant at a photography shop, where he also sleeps. When he meets a wealthy schoolgirl and innocently mistakes her smile for interest in companionship, he pursues her, hoping to be accepted as her house’s servant. The core of the narrative—rural man in the big city—is typical of Iranian cinema at the time, but the film offers a fresh angle, and not just because the weight of this familiar tale has been put on the shoulders of a child. Kiarostami’s formal approach is unique and delivers an early prototype of techniques that later gained him acclaim in films like Close-Up (1990). In one critical scene, when the young boy arrives at the girl’s house to speak to her mother about work, the details of conversation are blocked by the sounds of the street, thus lending the set-up a sense of sanctity, as though the moment is too private to be shared with an audience. Hossein Sabzian’s first interaction with Mohsen Makhmalbaf in the climax of Close-Up borrows heavily from this scene.

The Experience is among the director’s most emotionally charged films. In the finale, Mammad is suddenly facing a world far darker than his imagination and is forced to comprehend the harsh reality of class differences. Kiarostami portrays a picture of his rural protagonist that is empathetic, and never condescending. In the film’s final scene, an astonishing shot of Mammad filmed at a height from above, Kiarostami preserves the boy’s dignity by concealing his face and yet, emphasizing his desperation at the rejection. The director’s next film, The Traveler (1974), is a companion piece that also charts the voyage of a boy to the big city. Although the reasons for his path appear rather frivolous—he is desperate to see a live football game in the stadium in Tehran—Kiarostami searches for deeper and universal truths in his journey.

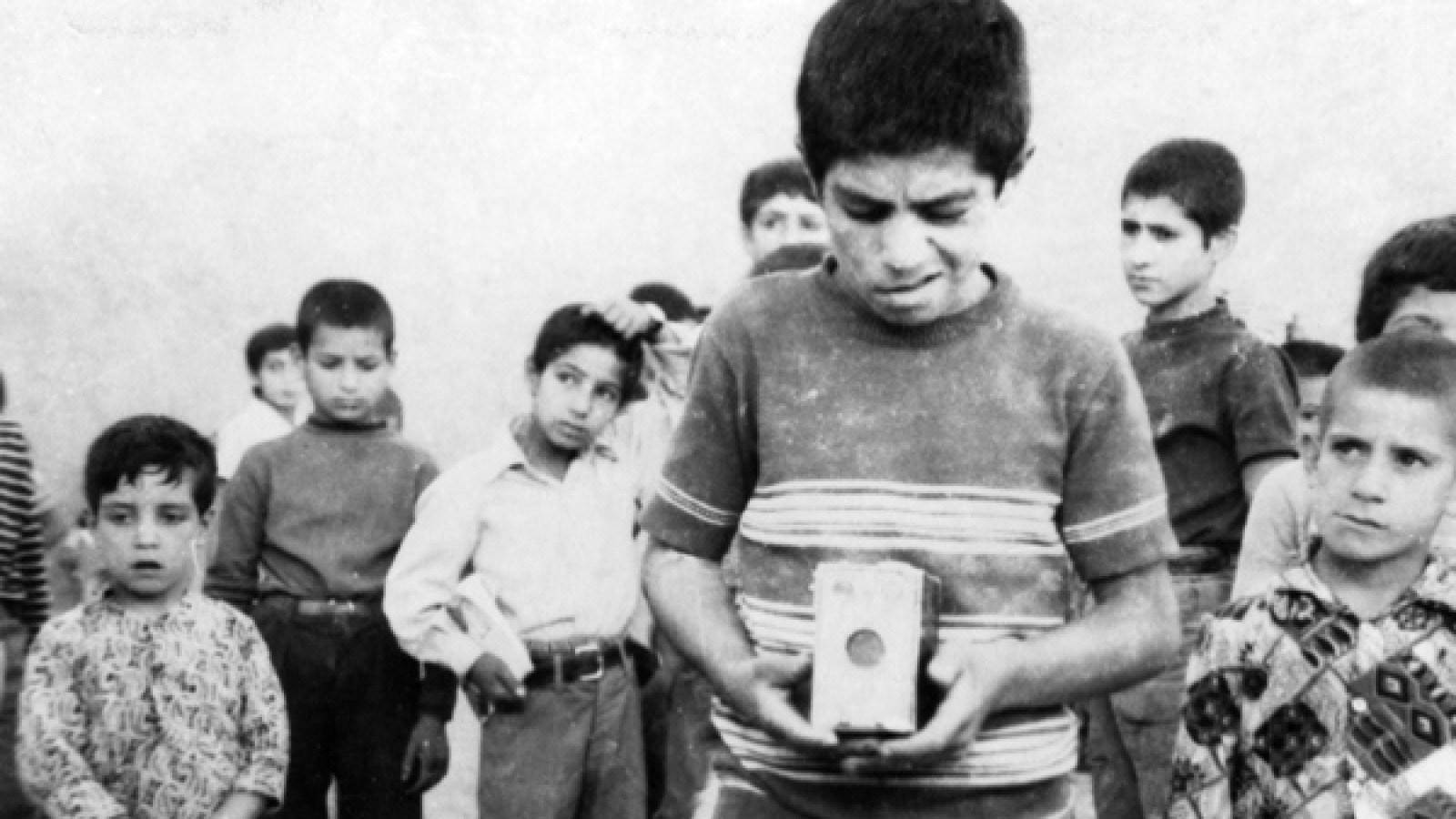

The Traveler is a keen observation on the Iranian society’s deep-rooted class divisions in the 1970s. Ostensibly a playful story about a young man named Qassem (Hassan Darabi), who goes to any length to collect enough money for a ticket to the football match—including duping his classmates into having their photographs taken with his broken camera—the film slyly criticizes the abject poverty of rural Iran at the time, which forbids the smallest joys in the kid’s life. Similar to The Experience, Qassem’s spiritual journey into adulthood comes with a heavy price and ends in despair. Though he navigates the dangers and difficulties of the unfamiliar urban milieu to finally get to the stadium, he falls into a deep sleep after the exhausting trip, and only wakes up to find the arena empty and the game finished. Yet again, Kiarostami delivers this revelation with graceful framing. The child, defeated and dejected, is lost in the empty whirlwind of the stadium. It’s a moment of heartbreak for him, and even more so for the audience.

Kiarostami’s next two narrative films with child protagonists are A Suit for the Wedding (1976) and First Case, Second Case ( 1979). The former is perhaps the only film in Kiarostami’s career that can be described as thrilling, a story with genuine suspense and dramatic tension set in a shopping arcade in southern Tehran. The latter is an ideological exercise about honesty and truth, and one of the few narrative films he made not just about children, but also directed at them. Yet, more than a decade later, Kiarostami would return to his heartbreak kids with the double punch of his monumental masterpiece, Where’s the Friend’s Home? and the documentary Homework (1989).

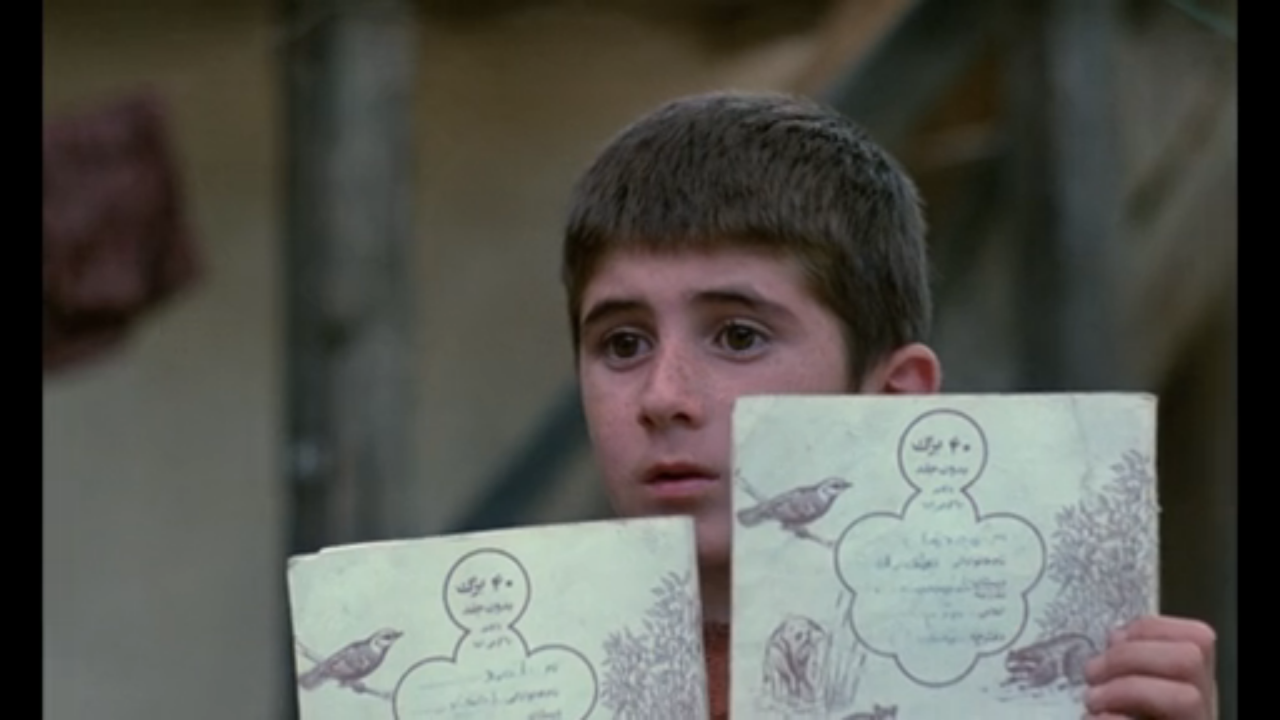

Friend’s Home, the film that catapulted the director to international fame, has a more hopeful tone. The young protagonist of this film, Ahmad (Babak Ahmadpour), discovers a classmate’s notebook in his bag and, knowing that the classmate will get reprimanded by the teacher, walks over to the next village to return the notebook. Not knowing his classmate’s address, his passage becomes increasingly complicated until darkness falls. Yet again, a young hero faces uncharted territory. The universe of this film isn’t entirely different from Kiarostami’s pre-revolutionary films about young children, where the overwhelming, alienating world of adults engulfs an astounded child. Like the previous heroes, Ahmad has the resolve to take on this world himself, though the film ends on a different note, bringing tears of joy and elation, not desperation.

In Homework, the bespectacled director interviews a series of young boys about their homework routines. Shot at a school in a dark room that creates a tense atmosphere for the children, Kiarostami digs deep into their psyches, uncovering secrets about their family lives and simultaneously exposing the broken methods of education in Iran at the time. The sequence of interviews with the boys, who are alternately playful, skeptical, inquisitive or visibly shaken, reverses the equation of the previous films. Thus, it is the adult—namely, the director himself, who was inspired to make the film based on his difficulties in dealing with his son’s schoolwork—who finds the children’s universe impenetrable. Homework is a shattering experience that, despite its short running time, works as a staunch critique of the Iranian school system, exposes the extent of financial misery in war-time Iran and rues the loss of moral purity in the transition from childhood to adulthood.

Kiarostami followed Homework with Close-Up and consequently never made another film with children as its focus. Yet, the towering importance of his work meant that arthouse films about children remained a significant element of Iranian cinema. Kiarostami influenced these productions to varying degrees: indirectly, with films such as Majid Majidi’s Children of Heaven that followed in his footsteps, or even directly, with the screenplay he wrote for Jafar Panahi’s directorial debut, The White Balloon, in which the archetypical Kiarostami protagonist is a young girl. Alongside other Kanoon productions such as Bashu, the Little Stranger and The Runner, Kiarostami’s child heroes have given Iranian cinema some of its most memorable characters.

2 thoughts on “The Child Heroes of Abbas Kiarostami’s Films”

Pingback: Daily | Film Comment, Brooklyn Rail - FANCY TEMPLE CELEBRITY

Pingback: The Child Heroes of Abbas Kiarostami’s Cinema – Amiresque