The film industry is no different from any other, in that, it unfortunately remains male-dominated. Last year was an especially poor showing for mainstream cinema, with only one film solely directed by a woman being released on more than 2000 screens (Kimberley Pierce with Carrie). While independent film has a better average, the fact remains that women are not permitted to direct major films and generally have a harder time. This despite all the evidence suggesting that Hollywood is missing out on opportunities (to say nothing of the sexism involved).

The sheer weight of this evidence should start to make a difference. When you consider the careers of women like Kathryn Bigelow (Hurt Locker) or Catherine Hardwicke (Twilight), one can take heart in studios tapping them for bigger and bigger films. Nancy Meyers, starting in the late 90s, is responsible for some of the most financially successful and profitable romantic comedies of the last couple of decades. After serving as a story artist on the first film, Jennifer Yuh Nelson was promoted to director for Kung Fu Panda 2, which made more financially than the first, and she is directing the third film, as well.

The issue is tricky, though, because it doesn’t feel fair to hold up these women like this when they are simply doing their job. But they are exceptions to the rule. They should prove to Hollywood that of course women can be entrusted with big budgets to make major films, that doing so should not be considered a “risk”.

Realistically, this is not the case, and it is useful to look at the amusing double standard when it comes to hiring men for gigantic blockbusters. While studios won’t “risk” their blockbusters with a female director, they’ll risk them time and time again with inexperienced male directors. Marc Webb made his directorial debut in 2009 with (500) Days of Summer, with a budget of $7.5 million. Then, Sony gave him control of $230 million for The Amazing Spider-Man. Gareth Edwards’ first film was Monsters, with a budget of about $500,000. Then, Warner Bros. gave him $160 million to make Godzilla and now he’s got a Star Wars movie next. Perhaps most bewildering, visual effects designer Robert Stromberg was given around $180 million to direct Maleficent – his very first film.

On the one hand, of course, one must congratulate these filmmakers for their express route to success, particularly someone like Edwards who clearly has the talent to justify these choices. That said, they are all, naturally, white and male. Studios are more than willing to take these risks on inexperienced white males, giving them responsibility over countless blockbusters and hundreds of millions of dollars, and yet women simply do not get the same opportunities, even though many admit they would be eager to. None of Marvel’s films have been directed by a woman, for example, and with Edgar Wright having dropped out of Ant-Man, all potential replacements the studio is in talks with are white males. I don’t mean to specifically pick on Marvel, for they are but one example of an industry-wide reluctance to hire women to direct big-budget films, while an inexperienced male is favored every time.

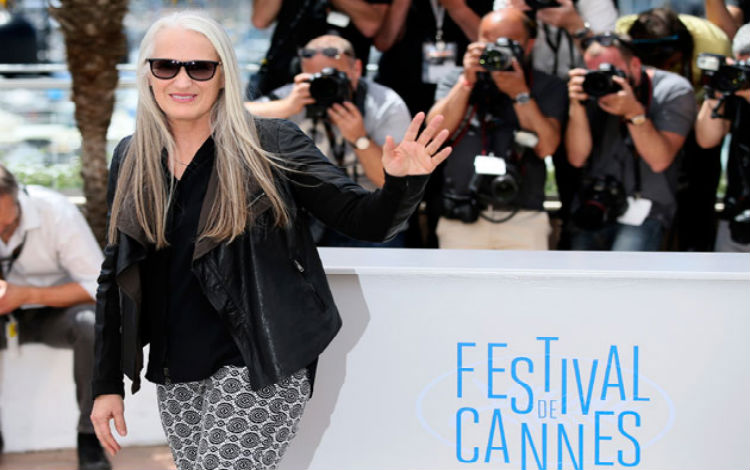

And while the independent side of the film industry has far more successful female directors, from Sofia Coppola to Jane Campion, it is not as inclusive as one might think. This year’s Cannes Film Festival had only two films directed by women screening in competition, leading Campion (who was the head of this year’s jury) to speak out: “It does feel very undemocratic and women do notice. Time and time again, we don’t get our share of representation.” We must be nearing a tipping point.

Campion may be directing The Flamethrowers next, the adaptation of Rachel Kushner’s novel. Her words when that news broke feel particularly resonant. “Filmmaking is not about whether you’re a man or a woman; it’s about sensitivity and hard work and really loving what you do. But women are going to tell different stories. There would be many more stories in the world if women were making more films.”

“It’s when business and commerce and art come together; somehow men trust men more.”