The following review has been republished from our AFI Film Festival coverage. It reviews the original Japanese dub, and not the newly released English dub.

If The Wind Rises is truly Hayao Miyazaki’s last film (and remember, this is the seventh time that he’s claimed he’s retiring), then it’s a fitting grace note to the director’s filmography. While it doesn’t hit the heights that audiences know Miyazaki’s work is capable of reaching, its meditation on passion for a craft serves as a love letter to the artistic process.

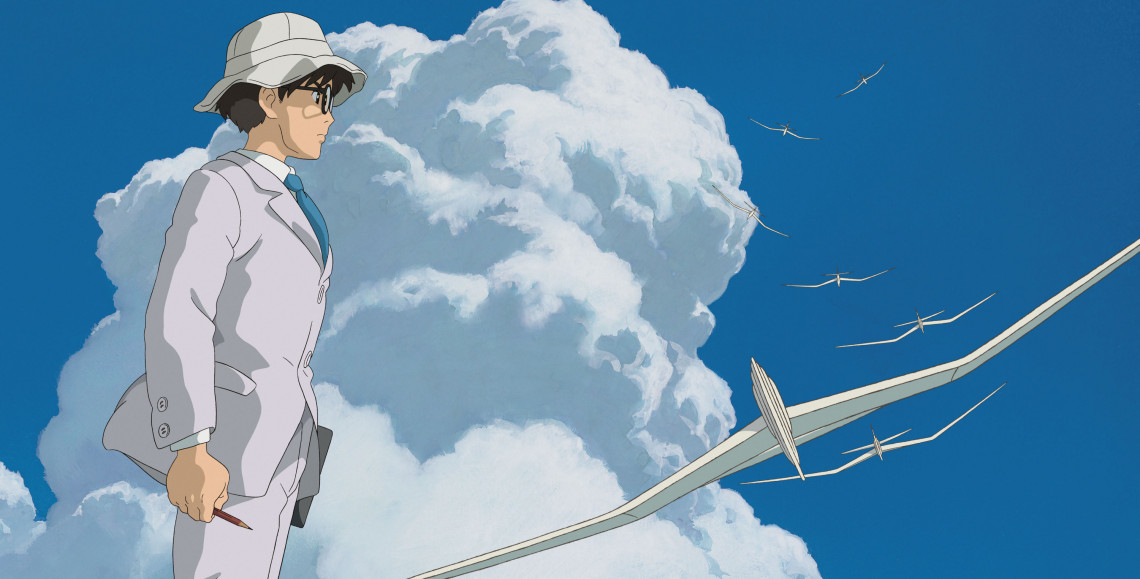

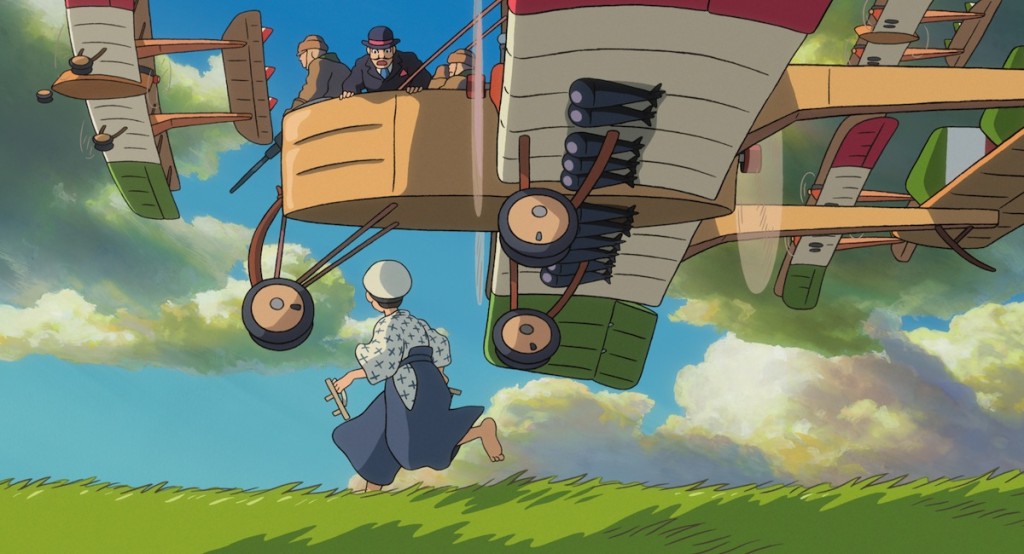

Of course, Jiro Horikoshi wasn’t an artist – he was an engineer. He designed the A6M Zero, the plane that saw infamously prolific use by the Japanese during World War II. The movie tracks Jiro from his childhood in turn-of-the-century Japan through the development of the A5M, the Zero’s predecessor, in 1935. In Miyazaki’s interpretation, Jiro is a dreamer, in love with airplanes and flight but unable to ever become a pilot due to his nearsightedness. In his sleep, he’s visited by his idol, Italian aircraft maker Giovanni Caproni, who tells him that it is far better to create planes than it is to fly them. Jiro takes this to heart and throws himself into the study of aeronautics, eventually getting a job at Mitsubishi. Meanwhile, his country experiences drastic social upheaval, and war looms on the horizon. Jiro loathes violence and knows that any plane he makes will have a machine gun fitted onto it, but he continues regardless because, as Caproni tells him, it’s better to live in a world with pyramids than one without them.

The Wind Rises is not like anything else Miyazaki has directed. It’s closest in spirit to Porco Rosso, but even that movie was propelled by an adventure plot. This is quieter. It’s no less visually lush than any of his other films, but the visuals are in the service of something much more personal and introspective. And while most of Miyazaki’s work has been rather chaste, The Wind Rises is partially a romance, chronicling Horikoshi’s romance with Naoko, his eventual wife.

That part of the plot is a curiosity. My efforts to find out how much of it is based in reality have proved frustratingly difficult. As best as I can tell, everything to do with Naoko is adapted from Tatsuo Hori’s short story The Wind Has Risen from 1936. The comic book by Miyazaki on which the film is based took both inspiration and its name from that story. Thus, The Wind Rises is an unusual hybrid of a biopic and adaptation. It would be terrific if this approach worked, but it doesn’t, since the two halves interfere with one another.

Jiro’s romance with Naoko provides an emotional counterpoint to the artistic love that he experiences in his work. He tries to strike the right balance between her and the AM5, while she fades away, suffering from tuberculosis. But their romance is not just badly developed, but an active detriment to the flow of the narrative. The two meet in a terrific sequence set during the 1923 Kanto earthquake, but she then fades out of sight and mind until the last third of the film. Then everything stops dead so that Jiro and Naoko can go through the motions of lovey-doveyness, while an inexplicable German character bungles about. The movie becomes flat-out boring in these sequences. Naoko is a paper character, existing more as an object than a partner for Jiro.

Other directionless subplots abound. Jiro’s sister Kayo drops in and out of the film, and could have been cut entirely without affecting anything else. Ghibli films have often found beauty in sequences that, while not necessary to their plots in any pragmatic sense, greatly enhance the mood they evoke. But in this case, the diversions create a listless feeling.

There are numerous hints to the dark fate that awaits Jiro’s goal, how he’s helping enable war. But the movie never goes beyond more than hinting. It’s entirely about the process of creation, much more than what happens when the creation is set loose. This is not an inherently invalid focus, but without the aftermath, how can the rumination on consequence have any meaning? World War II is relegated to the briefest of codas, in which Jiro flatly observes, “Oh yeah, I helped cause all this death.” It’s similar to Schindler’s List in this regard, another film that left out the most intriguing part of its subject’s life. It’s easy to revel in the excitement of creativity or saving lives, but what comes after is much more difficult. And ignoring the consequences of Jiro’s actions is morally hazardous at best.

Do not mourn Miyazaki’s career. In one dream sequence, Caproni admonishes Jiro that artists and engineers both only have 10 years of greatness in them, and that he should make the most of them. Miyazaki had 20 great years, and while I don’t count The Wind Rises as part of that greatness, it’s a fitting punctuation mark on every statement he’s made through his work.

5 thoughts on ““The Wind Rises”: A Gorgeous Film That Doesn’t Take Off”

The assertion that the romance aspect of this narrative was “flat-out boring” is a travesty. For me, it was one of Miyazaki’s greatest accomplishments. The relationship with Naoko taught us so much about who Jiro was. The doomed romance which drove Jiro is what made this story truly heartbreaking.

That romantic sub-plot fell flat for me as well. It was a device to flesh out Jiro’s character, but he seemed much more in love with his slide-rule than Naoko.

Boy, you crazy.

The craziest.

Seeing how ‘The Wind Rises’ is now in my top 3 Miyazaki films, this review doesn’t sit well with me. Easily one of his best works.