It’s the rare song that can be specifically written for one movie, in which context it becomes iconic, and then re-appropriated in completely different context and work equally as well. One such song is “Chaiyya Chaiyya,” (a rough English translation of which is “walk in the shade”) music by A.R. Rahman, lyrics by Gulzar, composed for the 1998 Bollywood romantic drama Dil Se. Rahman’s soaring melodies, relentlessly insistent refrain, and massive beat merge with Gulzar’s lyrics, so good you know exactly what they mean regardless if you don’t speak a word of Urdu.

Within five years “Chaiyya Chaiyya” was voted one of the ten best songs of all time in an international poll conducted by the BBC. Its popularity was further cemented by the jaw-dropping music video for the song, taken from the picturization in Dil Se featuring superstar Shahrukh Khan dancing on top of a moving train. Even after all this, the song managed to take on an entirely new dimension as the needle drop over the opening titles of Spike Lee’s superb heist picture Inside Man, in which, by magic, “Chaiyya Chaiyya” became an anthem of the richness and mystery of New York City. This is, in brief, quite the song.

The lyrics derive from an 18th century Sufi folk song by poet Bulleh Shah. Sufism being a discipline devoted to the perfection of worship, the poetry its adherents wrote is famous for his beauty and evocation of the divine. It’s not a thing to be used lightly, especially in a modern context, the invocation the glory of God and all His creation as a metaphor for romantic love.

The context in which the song first appears in Dil Se is a bit of a surprise. The film’s opening sequence sees the hero, journalist Amar (Shahrukh Khan), traveling in a remote section of India working on a story on the state of the nation as the 50th anniversary of independence approaches. In the middle of a rainy night, he encounters a woman (Manisha Koirala) alone at a railway station. Amar attempts to chat her up but she resists, and while he’s turning his head for a couple seconds getting a cup of tea, she leaves on a train with some mysterious men. He watches her go. And suddenly the world explodes into light.

Where a second ago, Amar is a mortal, a cocky young professional trying to pick up a pretty girl in a random setting, now he’s Shahrukh Khan dancing on top of a moving train, raising his (actually, Sukhwinder Singh’s) voice to the heavens, professing a love that can only be described in terms of its hints of the divine. It’s an exultation and exaltation unlike pretty much anything that’s ever been captured on a movie screen. The incomparably lovely dancer Malaika Arora is the stand-in for Manisha Koirala much in the way that the hero’s love needs to be described as literally heavenly.

Where a second ago, Amar is a mortal, a cocky young professional trying to pick up a pretty girl in a random setting, now he’s Shahrukh Khan dancing on top of a moving train, raising his (actually, Sukhwinder Singh’s) voice to the heavens, professing a love that can only be described in terms of its hints of the divine. It’s an exultation and exaltation unlike pretty much anything that’s ever been captured on a movie screen. The incomparably lovely dancer Malaika Arora is the stand-in for Manisha Koirala much in the way that the hero’s love needs to be described as literally heavenly.

When the song is over, the audience realizes that the seemingly innocuous encounter will transform Amar’s life. Dil Se follows through on the Sufi influence introduced by “Chaiyya Chaiyya” to become a story, on one hand, about the seven shades of love from classical Arabic literature (this influence explicitly stated by director Mani Ratnam): attraction, infatuation, love, reverence, worship, obsession, and death. On another, it’s a political thriller about a journalist who all too gradually realizes that the woman he’s fallen in instant, all-consuming love with, is a terrorist, her life no longer her own but entirely tied to her ability to pull off the plot her cell has in store for the 50th anniversary independence festivities.

Dil Se continues for almost two and a half more hours following “Chaiyya Chaiyya,” but is entirely set in motion by it. The energy of the song sustains the film through the setup of its plot, and establishes the running intertwined religion/love metaphor. And, let it not be forgotten, is a song of overwhelming, sensuous, endlessly rich beauty. And, let this not be forgotten either, it’s Shahrukh Khan dancing on top of a moving train. The number of male actors in the history of international cinema as effective at playing as deeply, madly immersed in love as Shahrukh Khan can be counted on one hand and are at best peers, not superiors. He’s had his ups and downs as an actor but at his best there is only one SRK, and there may not be any more perfectly distilled moment of pure essence of SRK than dancing on top of that train.

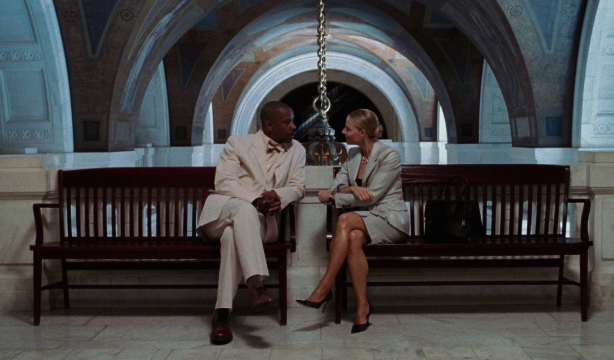

Which brings us to Spike Lee. The most amazing thing about his use of “Chaiyya Chaiyya” in Inside Man is that it’s at once completely separate from any of the song’s pre-existing cultural or even thematic context, seemingly a decision derived entirely from it being an awesome song and for no particularly deeper reason than that. Despite both of those conditions, it works nearly as well serving Spike’s end as it did in Dil Se. It is not the slightest bit of disrespect to Inside Man as a film to say that it’s less artistically and literarily ambitious than Dil Se. Inside Man is that harder-than-it-looks enterprise, the clever, intelligent heist movie. It features two excellent central performances by Denzel Washington as a cop and Clive Owen as his inscrutable adversary, and a thoroughly satisfying puzzle, even if most of it consists of “what the hell is Clive Owen doing?”

But, really, what makes Inside Man is Spike Lee’s direction. He is possessed of a near-peerless ability to make New York City come alive on a movie screen; a handful of Scorsese comes close, and if Woody Allen was able to do it for any other neighborhood than the Upper East Side, he would too. But aside from that, Spike Lee is the king of New York. The most important reason for this, besides the obvious (being really talented) is that he recognizes the importance of multiculturalism to New York’s identity as a city. Further, one point of New York pride, tied into it being the birthplace of hip-hop as well as being the fashion capital of North America, is that of New Yorkers’ (self-attributed) ability to pick out the hottest beats out there. And, all the above-mentioned poetic richness and melodic grandeur of “Chaiyya Chaiyya” aside, it has one extremely hot beat.

But, really, what makes Inside Man is Spike Lee’s direction. He is possessed of a near-peerless ability to make New York City come alive on a movie screen; a handful of Scorsese comes close, and if Woody Allen was able to do it for any other neighborhood than the Upper East Side, he would too. But aside from that, Spike Lee is the king of New York. The most important reason for this, besides the obvious (being really talented) is that he recognizes the importance of multiculturalism to New York’s identity as a city. Further, one point of New York pride, tied into it being the birthplace of hip-hop as well as being the fashion capital of North America, is that of New Yorkers’ (self-attributed) ability to pick out the hottest beats out there. And, all the above-mentioned poetic richness and melodic grandeur of “Chaiyya Chaiyya” aside, it has one extremely hot beat.

Even on that most superficial level, the song still does exactly what Inside Man needs it to. It gets the audience—many of whom were previously unaware of this song, the parallelism and lack of overlap between Bollywood and Hollywood being what it is—nodding its head going “Nice.” Stripping the song of its literary resonance and employing it strictly for its surface-level visceral qualities may sound like a bit of a waste, but those surface-level charms are there. And there is an aesthetic value to, as Spike Lee did here, pointing out how great something is.

“Chaiyya Chaiyya” is not the first song to be repurposed in completely different context, nor will it be the last. But it stands as an instructive example to the many dimensions in which music (in particular, among all the arts) exists. There is the level on which it was created, and the attendant context. But with each additional listener, music creates different and new levels on which it exists. These new ones don’t cancel out any others. All exist at once. All walking side by side in the shade.