Last night, CNN aired Steve James’ lovingly intimate documentary on the life and work of the iconic Roger Ebert, Life Itself. An incredibly sensitive portrait examining his strength, influence, and humanity, the doc contains excerpts from his criticism from throughout his long career, and we even get glimpses into his writing patterns. We at the Balcony would like to commemorate the premiere of that doc by having a little celebration of Ebert’s work with some of his most memorable Great Movies essays, the pieces where he shone a light on some of his favorite films and some of the most important works in cinema. Certainly as impressive as his general reviews, his Great Movies series had a special intimacy and insight about them that seemed to be devoid elsewhere in film criticism. Here are some of my favorite pieces from the series.

David Fincher’s Seven

What’s being used here is the same sort of approach William Friedkin employed in The Exorcist and Jonathan Demme in The Silence of the Lambs. What could become a routine cop movie is elevated by the evocation of dread mythology and symbolism. Seven is not really a very deep or profound film, but it provides the convincing illusion of one. Almost all mainstream thrillers seek first to provide entertainment; this one intends to fascinate and appall. By giving the impression of scholarship, Detective Somerset lends a depth and significance to what the killer apparently considers moral statements. To be sure, Somerset lucks out in finding that the killer has a library card, although with this killer, thinking back, you figure he didn’t get his ideas in the library, and checked out those books to lure the police.

Sofia Coppola’s Lost in Translation

I can’t tell you how many people have told me that just don’t get Lost in Translation. They want to know what it’s about. They complain ‘nothing happens.’ They’ve been trained by movies that tell them where to look and what to feel, in stories that have a beginning, a middle and an end. Lost in Translation offers an experience in the exercise of empathy. The characters empathize with each other (that’s what it’s about), and we can empathize with them going through that process. It’s not a question of reading our own emotions into Murray’s blank slate. The slate isn’t blank. It’s on hold. He doesn’t choose to wear his heart on his sleeve for Charlotte, and he doesn’t choose to make a move. But he is very lonely and not without sympathy for her. She would plausibly have sex with him, casually, to be “nice,” and because she’s mad at her husband and it might be fun. But she doesn’t know as he does that if you cheat it shouldn’t be with someone it would make a difference to.

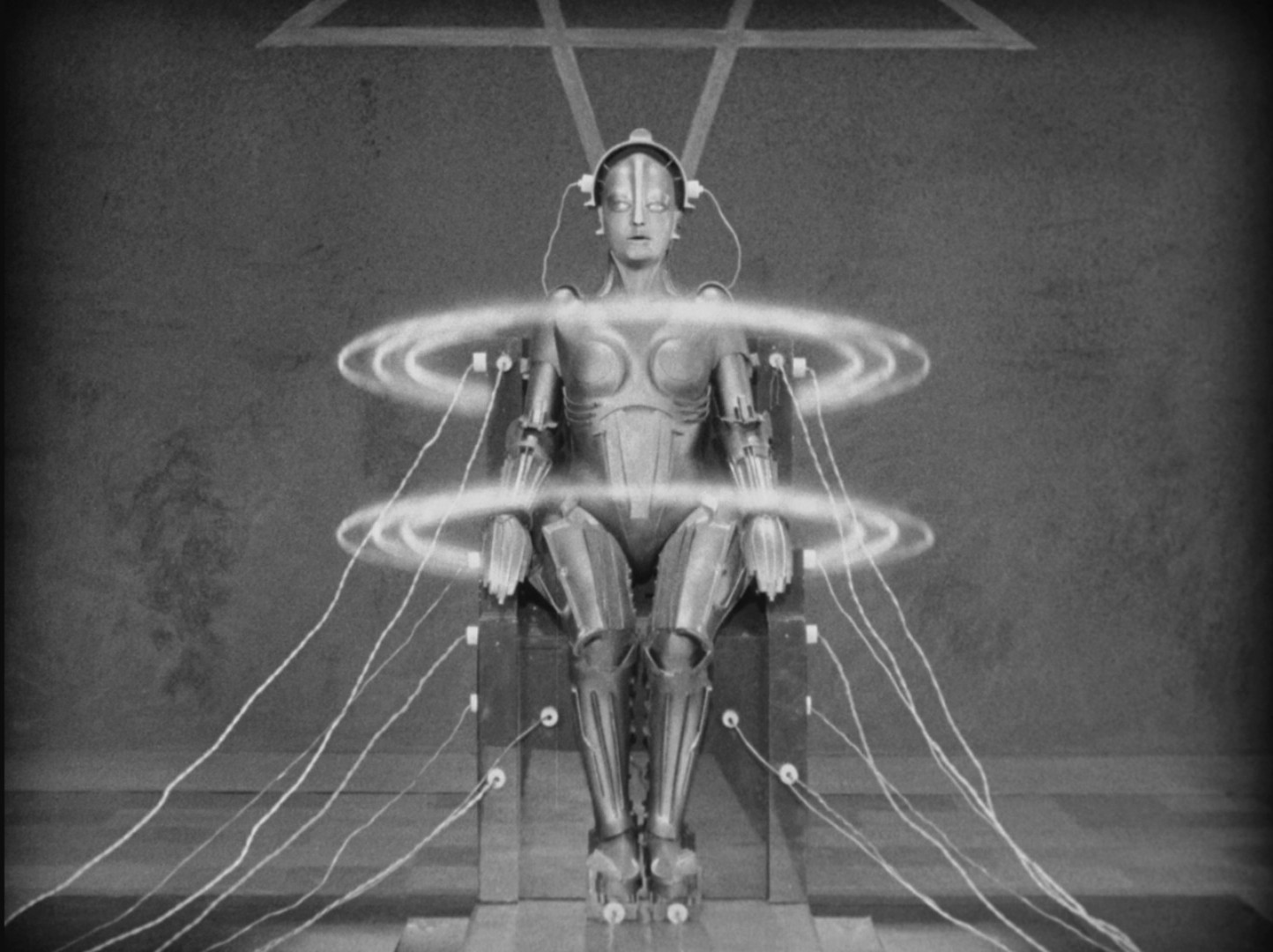

Fritz Lang’s Metropolis

Lang created one of the unforgettable original places in the cinema. Metropolis fixed for countless later films the image of a futuristic city as a hell of material progress and human despair. From this film, in various ways, descended not only Dark City but Blade Runner, The Fifth Element, Alphaville, Escape From L.A., Gattaca and Batman’s Gotham City. The laboratory of its evil genius, Rotwang, created the visual look of mad scientists for decades to come, especially after it was so closely mirrored in Bride of Frankenstein (1935). The device of the “false Maria,” the robot who looks like a human being, inspired the Replicants of Blade Runner. Even Rotwang’s artificial hand was given homage in Dr. Strangelove.

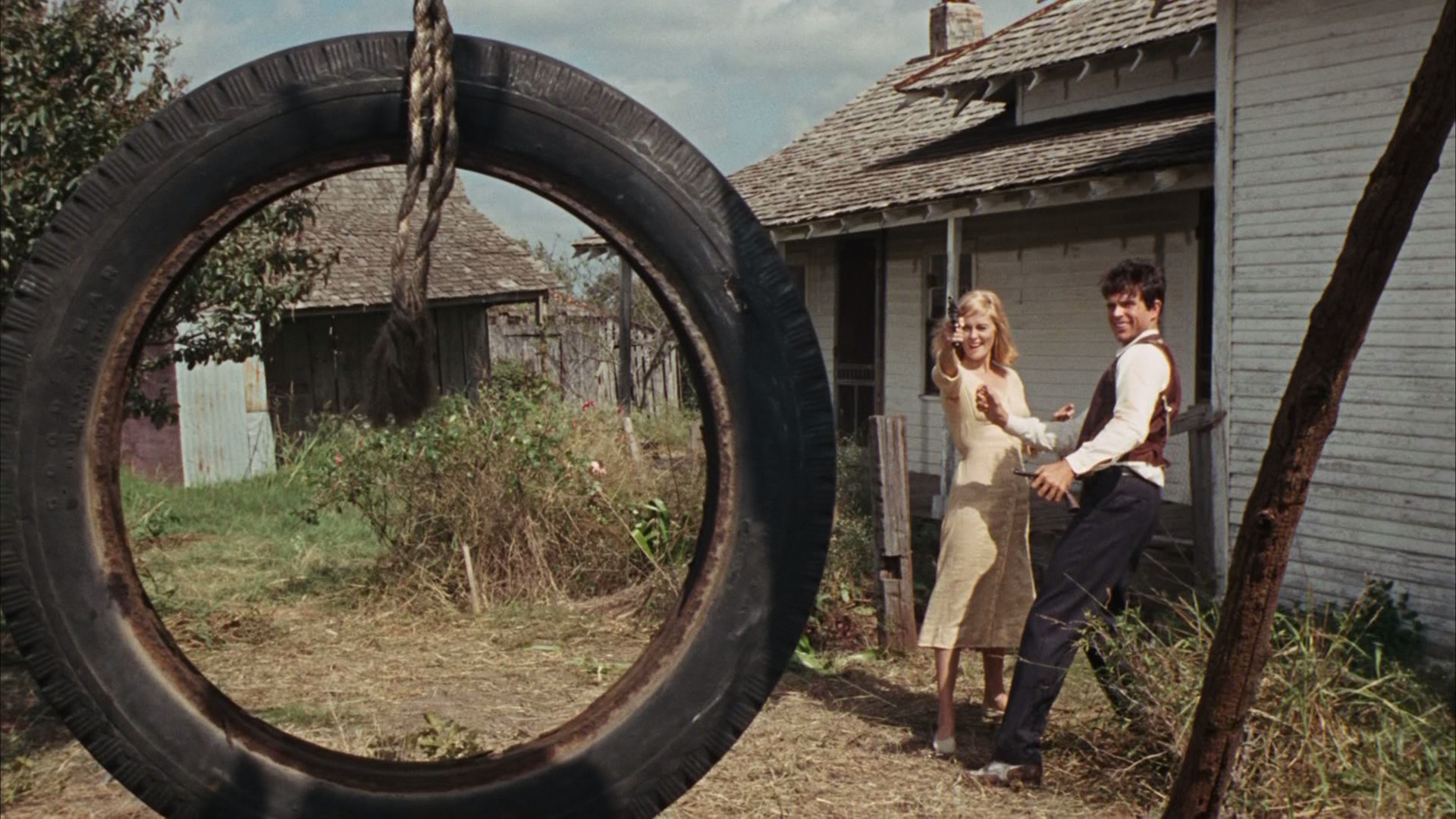

Arthur Penn’s Bonnie and Clyde

If Clyde offers glamour, Bonnie offers publicity. She writes ‘The Ballad of Bonnie and Clyde’ and sends it to a newspaper, and she poses for photos holding a machinegun and a cigar. Clyde’s brother Buck (Hackman) is more level-headed, more concerned with bank jobs than newspaper headlines. He comes attached to Blanche (Parsons), whose whiny complaints get on Bonnie’s nerves (when agents surround one of their hideouts, she runs screaming across the lawn, still holding the spatula she was using to cook supper).

Federico Fellini’s La Dolce Vita

Movies do not change, but their viewers do. When I saw La Dolce Vita in 1960, I was an adolescent for whom “the sweet life” represented everything I dreamed of: sin, exotic European glamour, the weary romance of the cynical newspaperman. When I saw it again, around 1970, I was living in a version of Marcello’s world; Chicago’s North Avenue was not the Via Veneto, but at 3 a.m. the denizens were just as colorful, and I was about Marcello’s age.

When I saw the movie around 1980, Marcello was the same age, but I was 10 years older, had stopped drinking, and saw him not as a role model but as a victim, condemned to an endless search for happiness that could never be found, not that way. By 1991, when I analyzed the film a frame at a time at the University of Colorado, Marcello seemed younger still, and while I had once admired and then criticized him, now I pitied and loved him. And when I saw the movie right after Mastroianni died, I thought that Fellini and Marcello had taken a moment of discovery and made it immortal. There may be no such thing as the sweet life. But it is necessary to find that out for yourself.

2 thoughts on “The Great Movies Life: Roger Ebert’s Best Essays”

Fantastic choices all around (you can’t go wrong with the La Dolce Vita essay) but I’d like to give a shoutout to the two final paragraph of his Great Movie essay for Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind. They kill me.

God, I love that essay on LiT…. that makes me so happy that my favorite film ever is among one of his all-time favorites.