There’s no single path that leads to directing a film–some dive right behind the camera as their first job, others work up to it after years of toiling as assistant directors, and then others get the gig because of their work in front of the camera coupled with the right amount of curiosity. (And potentially a built-in audience that might buy a ticket for a film directed by a well-known actor.) With the latest film directed by an actor–Pitch Perfect 2, by first-timer Elizabeth Banks–being a huge box-office smash, the Movie Mezzanine staff thought it best to dive through a century of cinema and pick out the very best actors-turned-directors, as well as each of their best and worst films. Read on, debate, and enjoy.

Singin’ in the Rain is not so much about the magic of movies as it is about the flimsy artifice upon which the industry is built. In Gene Kelly’s sophomore co-directing effort with Stanley Donen, Kelly stars as silent-era matinee idol Don Lockwood, one-half of the silver-screen couple Lockwood & Lamont (with Jean Hagen playing spoiled diva Lina) whose careers are put in jeopardy when talkies take over Hollywood, as Lina’s squeaky voice will kill her image as an ultra-refined movie star. Thus, Don conspires to replace Lina’s voice, and eventually Lina herself, with that of the far-more-talented Kathy Selden (Debbie Reynolds). What has made Singin’ in the Rain endure beyond its celebrated musical numbers is how Kelly and Donen cleverly peel away the layers of movie trickery. One moment near the end illustrates this perfectly. In it, we see Lina singing (terribly) live on set in full costume; then the film dissolves to Kathy recording over her vocals, and then it dissolves to the finished film (with Kathy’s voice subbing for Lina’s) playing for a rapt audience. Even more extraordinary: In this scene, Jean Hagen is actually subbing in for Debbie Reynolds’ singing voice, bringing the illusion full circle.

If Singin’ in the Rain strips away Hollywod artifice, then Kelly’s solo outing, Hello, Dolly! (1969) embraces it wholeheartedly. What results is a bloated, two-hour mess. Feisty Dolly Levi (Barbra Streisand) is a renowned matchmaker in the 1890s who for some reason has romantic designs on “half a millionaire” Horace Vandergelder (Walter Matthau, sleepwalking through this grumpy-old-man role). Identity mix-ups, hasty proclamations of love, and chaos ensue, culminating in a climatic sequence in the lavish Harmonia Gardens Restaurant. Kelly’s vision of late-19th century New York is overblown and garish, with colorful costumes, elaborate sets, and large-scale musical set pieces with multitudes of choreographed extras. So much is happening onscreen at once that the sensory overload results in a boring mishmash. One wonders if Donen was the true visionary behind Kelly’s previous directorial successes—the Donen-helmed Charade (aka, the best movie Hitchcock never made), seems to be proof positive. – Mallory Andrews

“When you’re in the middle of a story, it isn’t a story at all but rather a confusion,” says Sarah Polley’s father in her third film, Stories We Tell. It’s an ethos that has guided Polley’s filmmaking ever since her directorial debut Away From Her and has made her work stand out from the more tightly wound puzzle-box films which have found success in the North American independent scene. She embraces the “wreckage of shattered glass and splintered wood” of life that her father talks about. Her second film, Take This Waltz, encapsulates this point-of-view, winding its way through the disillusionment of a woman, Margot, in an ostensibly good marriage, but one in which she is unfulfilled. Polley paints for Margot a world—a vibrant, colorful, distinctly unreal Toronto—in which to explore her urges, to satisfy her lusts, and, most crucially, to fail. For all its bubbly surfaces, Take This Waltz is often an alienating film, putting the audience in Margot’s headspace but then confronting us with the complicated reality of her needs, wants and choices.

It’s a film that’s easy to look upon with disdain, for it is messy and imperfect, and it so resolutely refuses to pass judgment on its characters or call their actions mistakes—finding instead a beauty in the truth of their being. It’s also a film made more affecting after watching Polley’s next effort, the documentary Stories We Tell, about herself, her surprising lineage, and her mother, who exists now only in a collection of home movies and the passed-along memories of the people who knew her. At several points in Stories We Tell, Polley positions the film as an exploration of the slippery nature of truth, a Rashomon-like story of varied viewpoints and ambiguous histories. But the film itself isn’t as interested in the nature of truth as it is in the truthiness of relationships. The film is an elegy for a mother Polley hardly knew, but whose memory and image have defined so much of what Polley understands about the world. When that image is rocked and the memory begins to splinter, the messiness and truths discovered form themselves into something overwhelming. The decisions we make, Polley suggests in her films, exist in a morass of misunderstanding and emotion, but also breathe in us the untamable spirit and unknowable energy that make life such a glorious waltz. – Corey Atad

Mel Brooks, one of the true kings of American comedy, is best known for his spoofs of Westerns, Alfred Hitchcock films, silent pictures, and more, but his highest and lowest points came when he tackled the same genre: old-school horror. His best film is Young Frankenstein precisely because it doesn’t feel like a spoof so much as a fully lived-in film. His care and dedication to the Frankenstein story, now seemingly the stuff of myth, is present in the black-and-white photography and production design. (He was able to use some of the sets from James Whale’s film, and you can tell; the age of the objects merely adds to the inherently spooky quality.) Being a Brooks picture, Young Frankenstein is as ridiculous and goofy as you might expect, what with a marble-mouthed sheriff, a hausfrau whose name frightens horses, and a monster with an unexpectedly powerful libido. But Young Frankenstein is surprisingly respectful of its source, and that maturity shines through 40 years later.

However, Brooks’ last film to date, Dracula: Dead and Loving It, is much less successful in spite of being indebted to many of the same tropes as Young Frankenstein. It would seem like a match made in heaven: Mel Brooks and Leslie Nielsen, together for the first time! And Nielsen is predictably game for anything, as is the rest of the cast, including Steven Weber and Peter MacNicol. But where there’s a distinct sense of underplaying the comedy in Young Frankenstein, everyone’s aiming for the rafters in Dracula: Dead and Loving It. The 1995 film was the latest in a string of Brooks spoofs less about a genre and more about a specific cultural phenomenon; it’s more a parody of Francis Ford Coppola’s 1992 take on the famed vampire, just as Robin Hood: Men in Tights targeted the Kevin Costner vehicle from 1991. Young Frankenstein is timeless; Dracula: Dead and Loving It is a time capsule, musty upon being opened after far too long underground. – Josh Spiegel

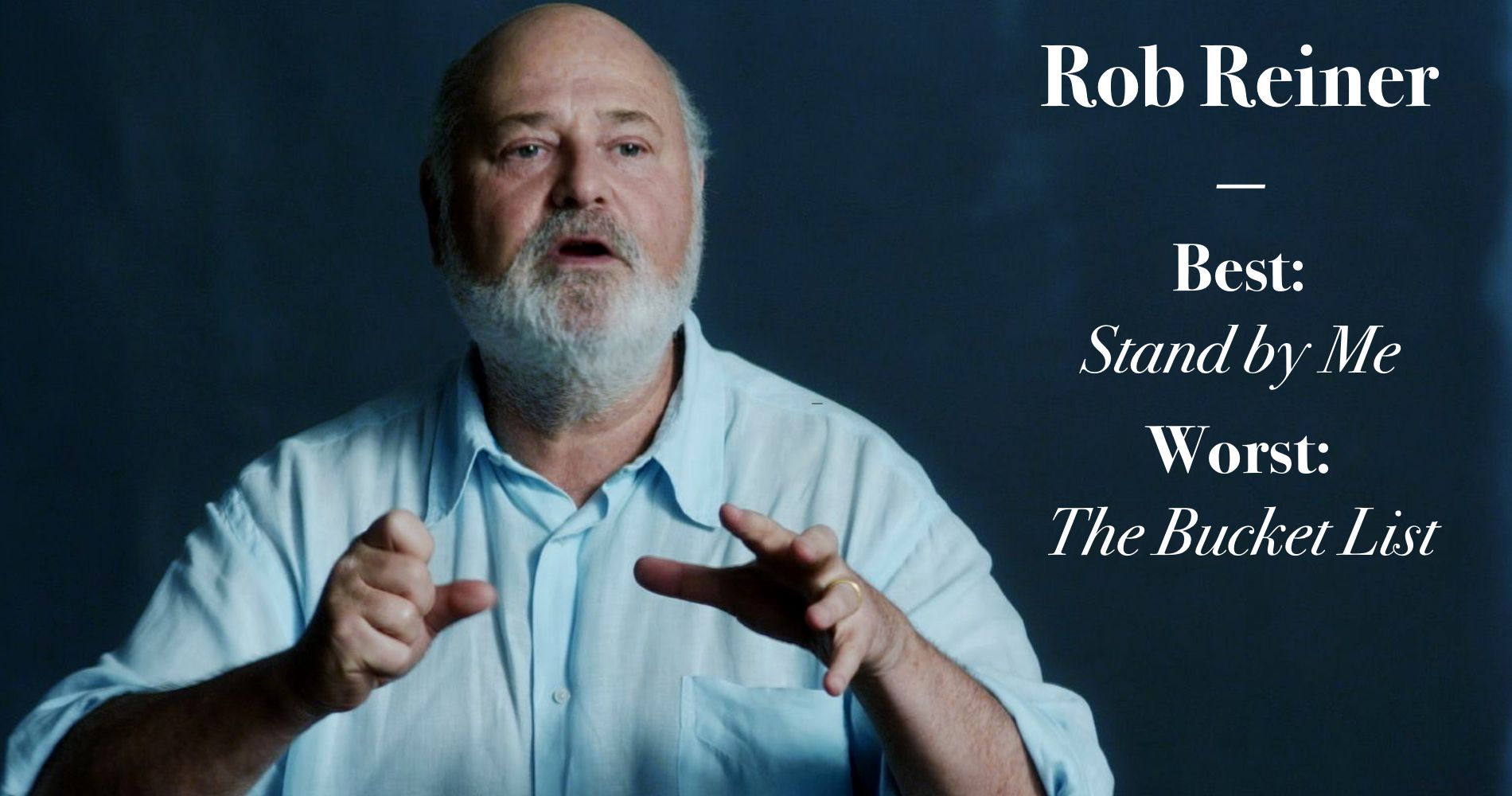

There was a time in American film when Rob Reiner could do no wrong. In the span of only five years, he went from capturing the imaginations of ’80s kids with The Princess Bride (1987) to helming a defining modern romance in When Harry Met Sally… (1989) to helping create an instantly iconic moment in Jack Nicholson’s filmography with A Few Good Men (1992). And of course there’s This is Spinal Tap, whose influence is still deeply felt in the comedy community 31 years later. But in many ways, Reiner was a quintessential journeyman director, capable of jumping genres without breaking a sweat and savvy enough to not get in the way of talented actors. You only have to look at Stand By Me, his 1986 adaptation of a Stephen King novella, for proof. It’s a coming-of-age story about a group of teenage boys on an adventure through the woods to see a real corpse up close; to paraphrase the axiom, the journey matters more here, as do those partaking in it. Getting to know Gordie (Wil Wheaton) and Chris (River Phoenix) is more exciting than wondering what the corpse will look like. Stand By Me is one of the great cinematic bildungsromans, a knowing and wistful look at the past with a wry and cutting sense of humor throughout.

The very opposite of that is one of Reiner’s later films, the 2007 feel-good crowd-pleaser The Bucket List. In what is essentially “Grumpily Dying Old Men,” Morgan Freeman and Jack Nicholson go on a journey of their own to mark off entries on a so-called bucket list before becoming a corpse that kids like Gordie and Chris would want to rush to see. Movies where old people get to tell it like it is and finally cut loose and so on are painfully old hat by now (and were equally so in the mid-2000s), even when those old people are icons like Freeman and Nicholson. It’s just one of many late-period embarrassments for Reiner; his worst could just as easily be Alex and Emma (2003), Rumor Has It… (2005) or the infamous 1994 film North, whose ignominy is entirely thanks to a hilariously on-point and vitriolic review from the late Roger Ebert. Maybe Rob Reiner still has some talent left in him to direct another great film. Or maybe he crossed off all the entries on his bucket list already. – Josh Spiegel

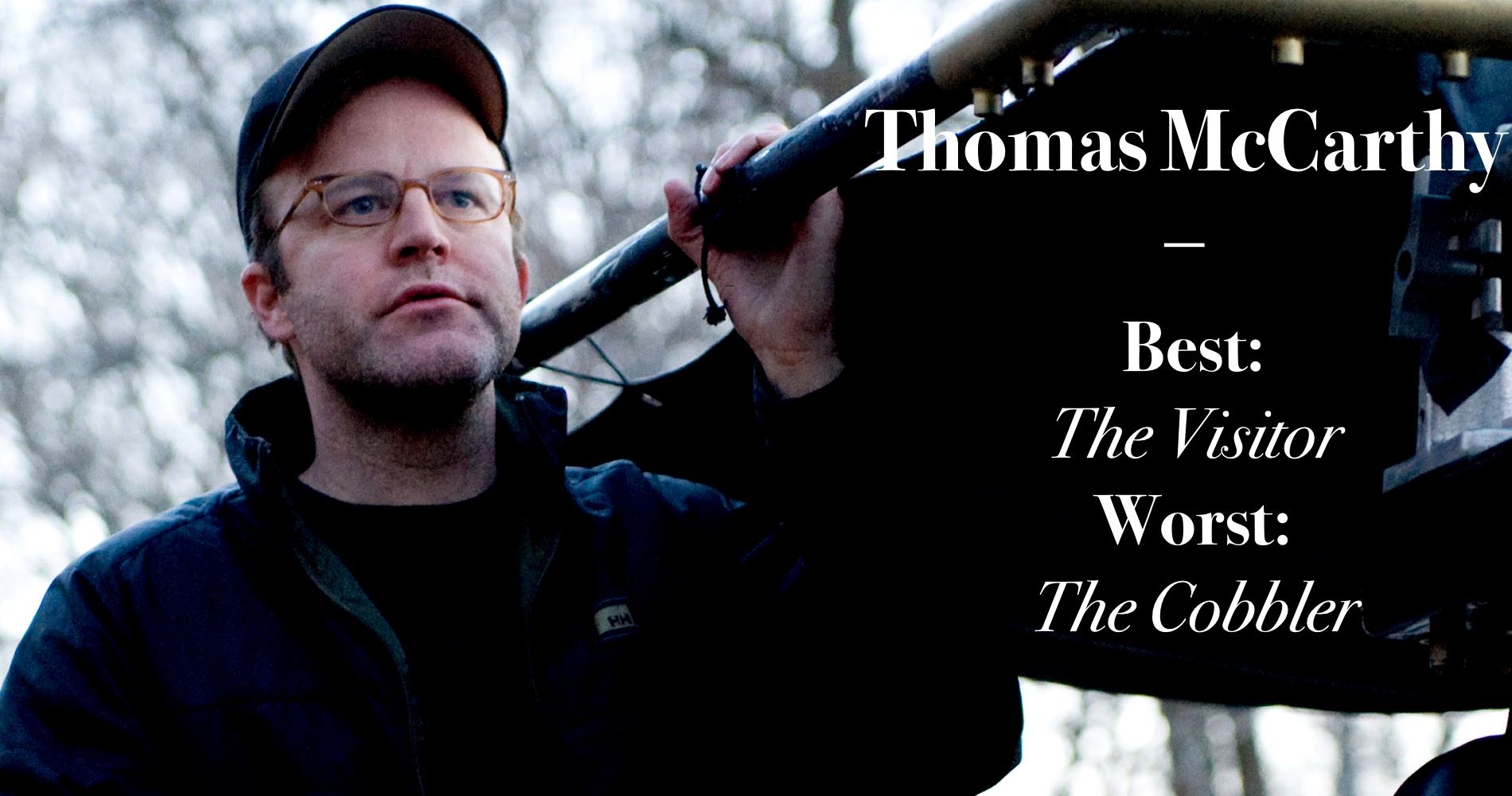

Thomas McCarthy is one of a few filmmakers for whom the word quirky needn’t be prescribed as a pejorative. To McCarthy, in his understated comic dramas The Station Agent, The Visitor, Win Win, and – to a lesser extent – The Cobbler, the idiosyncratic lightness of real life is not merely for laughs, but the relief to its at-times unbearable drama. McCarthy’s films are obsessively warm-hearted and human, ending on hopeful notes even though the odds on true happiness are stacked against the protagonists. This is a writer-director that wants his small-town characters to succeed, whether they’re irritable loners (Peter Dinklage’s Finbar McBride in The Station Agent, Richard Jenkins’ Walter Vale in The Visitor) or wrongdoers behaving selfishly despite their better judgment (Paul Giamatti’s Mike Flaherty in Win Win, Adam Sandler’s Max Simkin in The Cobbler).

McCarthy’s leads are invariably unremarkable men, liable to disappear in the crowd – like McCarthy himself. He displays the same quiet, thoughtful nature as director as he does as an actor, but where his ordinariness never translated to great success as a big screen thesp (it’s actually on the small screen, as “The Wire”’s unscrupulous journalist Scott Templeton, where McCarthy has to date excelled best as a performer), the same personality behind the camera creates everyday magic. Small-scale cinema is McCarthy’s domain – here, he revels in the chance to remind you of the wonder in normal working-class life.

There’s a feeling McCarthy’s latest film, magic-realist Adam Sandler vehicle The Cobbler, was a mere commercial stepping stone to secure McCarthy the funding for Spotlight, his more obviously suited (and higher-profile) upcoming fifth movie about Boston journalists uncovering child abuse in the Catholic Church. Even so, The Cobbler isn’t a complete hack-y write-off. It’s nonsensical and never that funny, and the final twist is awful, but even hemmed into the lowbrow confines of an Adam Sandler movie, the innate humanity of the filmmaker allows him to achieve the impossible: he makes a Sandler film watchable, less offensive than is expected, and occasionally actually charming. — Brogan Morris

4 thoughts on “The 19 Best Actors-Turned-Directors”

The Bling Ring was awesome! I oughta kick your ass!!!!!!

Um, this list is less than astute.

No Woody Allen? On a site edited by Woody lover Sam, I’m shocked. (Giggle. I just called seriously hetero Sam a woody lover, no pun intended).

And no Ron Howard?

Really those two omissions alone leaves the list invalid.

Not to mention Laurence Olivier, John Cassavetes, Mel Gibson, Jodie Foster and Kevin Costner.

I guess you can argue that John Huston was a director first and an actor second — so I give the staff a pass on him.

And since Charles Laughton only directed one film — a masterpiece, though — he wouldn’t qualify.

You consider Sofia Coppola an actor? Bury the lede why don’t you.

The General his worst?? Did we even watch the same film??? “Missing heart, thrill, and excitement.” You must be nuts.