5.) Public Enemies (2009)

If any Mann film deserves another look, it’s this underappreciated biopic of John Dillinger. Among its many virtues, Public Enemies includes one of Johnny Depp’s best performances (especially in light of his indifferent recent work), making the Depression-era gangster understandable without turning him into a martyr. Mann again uses digital photography to create a truly original look: He’s not afraid to show images that are occasionally blurry and out-of-focus, or have the camera pull up close to characters walking rapidly down the street in order to create a claustrophobic effect. When Dillinger and his guys stroll up the steps to rob a bank, Mann brings us right next to them; he uses a similar approach in following the forces of FBI agent Melvin Purvis (Christian Bale) as they close in on Dillinger’s gang. Mann avoids the “rise-and-fall” narrative typical of most gangster films; instead, Public Enemies dramatizes the end of an era, with organized criminals like Frank Nitti (Bill Camp) replacing daring outlaws like Dillinger. The result is a period piece that feels truly modern.

4.) Collateral (2004)

Mann returns to the spare approach of Thief with this intriguing look at two very different men in the course of a single night. Jamie Foxx’s Max is an everyman cab driver who has the bad luck to pick up a contract killer: Vincent, played by Tom Cruise in a risky, daring performance. Much of the film simply involves the two guys playing off each other, with Vincent and Max discussing their world-views. Vincent is an existential loner who’s indifferent to killing, at one point railing against the hypocrisy of caring for dead nobodies while barely batting an eye toward, say, mass killings in Rwanda; Max, however, isn’t ready to give up on humanity just yet. As the stakes rise, though, Max is forced to help Vincent carry out his contract killings, and the film’s suspense lies in seeing him try to escape his clutches. In spite of a final act that becomes a bit too generic by turning Vincent into a one-dimensional villain, the film’s philosophical implications linger in the eerie Los Angeles night air.

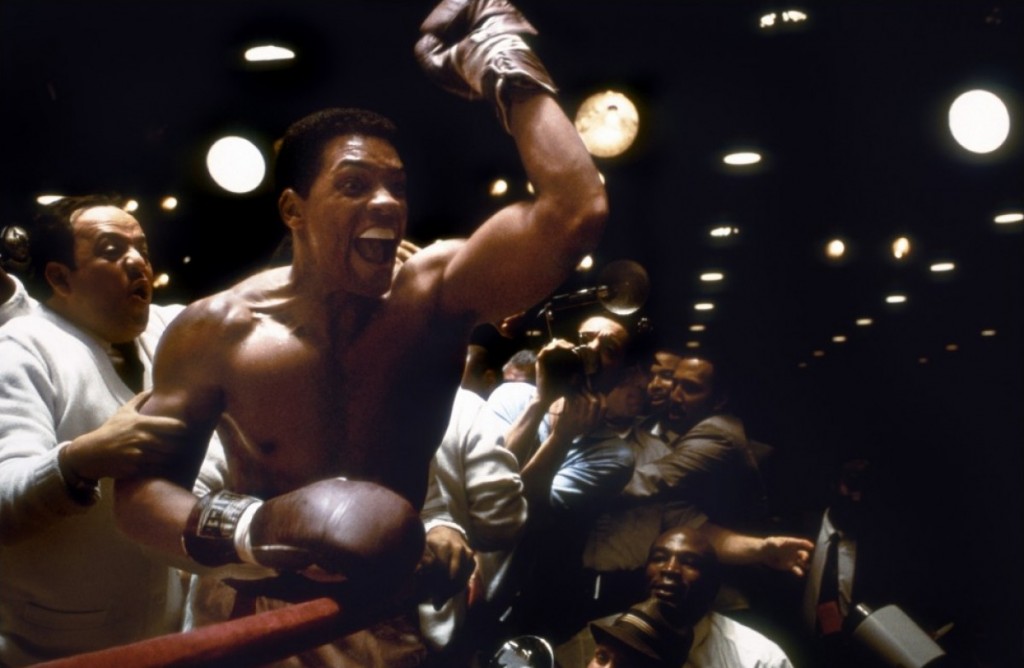

3.) Ali (2001)

Going into this film, one would expect Will Smith as Muhammad Ali to convincingly portray the boxing legend’s blustery side, showing off and taunting opponents. What’s surprising in Ali, though, is how well he plays the quiet scenes, too: Simple actions like jogging through town or riding in a car feel more significant because Smith is able to convey the pressure on Ali simply through vivid facial expressions. Mann wisely doesn’t try to cover Ali’s entire life, instead honing in on the 10-year period beginning in 1964 with his defeat of Sonny Liston to win the heavyweight title; this allows him to reveal a lot more about Ali and his reasons for refusing to be drafted for the Vietnam War. The fight scenes rank alongside sequences in Raging Bull, Cinderella Man, and the original Rocky as among cinema’s finest, with Emmanuel Lubezki’s camera pulling much closer to the fighters than expected, thus revealing the sport’s raw intensity.

2.) The Insider

Despite working outside the crime world, Mann brings a similar mentality to the real-life story of whistleblower Jeffrey Wigand (Russell Crowe) who publicly exposed the lies of the tobacco industry. The opening sequence with a blindfolded 60 Minutes producer Lowell Bergman (Al Pacino) visiting Iran to set up an interview with the Sheikh Fadlallah plays like the start of an action thriller; this heightened tension remains once the central plot kicks into gear, especially during the crackling dialogue scenes with Bergman and correspondent Mike Wallace (Christopher Plummer). The Insider is about a lot more than corporate malfeasance: In its depiction of a major TV news show bowing to business interests, it foretells the unfortunate state of network journalism today, one in which journalistic ethics is considered secondary to the economic bottom line. If nothing else, the moment in which trial attorney Ron Motley (Bruce McGill) tears into a tobacco-industry lawyer in court is one of the highlights of Mann’s career.

1.) Heat

There’s a reason that Mann’s known for directing crime epics. This elegant mix of the heist and straight-up action genres draws the best from both worlds. Al Pacino and Robert De Niro have rarely been this good, with each creating a realistic and captivating character while facing off on opposite sides of the law; De Niro, especially, brings a quiet confidence to master thief Neil McCauley that makes it heartbreaking when he makes a wrong choice. The blistering centerpiece shootout on the streets of Los Angeles has lost none of its luster in the past 20 years, but it’s because Mann has given us time to know the characters involved that it is as emotionally affecting as it is viscerally thrilling. For its combination of visual brilliance and dramatic depth, Heat remains Mann’s crowning achievement.