Look out, cinema world! There’s a new contender for the title of “Film with Showiest Long Takes.” Notwithstanding a handful of conventionally filmed and edited shots, Dennis Hauck’s crime drama Too Late is primarily made up of five 20-something-minute long takes, all meant to simulate real time—a gimmick bolstered by the writer/director’s decision to shoot the film on Techniscope, a format that allows for up to 22 minutes of runtime per reel—double the standard for other formats. The film comes hot on the heels of Birdman and The Revenant, in which director Alejandro González Iñárritu experimented with the possibilities of the long take—by shooting almost all of Birdman in (what is designed to look like) one take, and by building The Revenant around many long takes, most of them meant to intensify the harrowing spectacle of Leonardo DiCaprio enduring physical punishment for the sake of survival. On the world-cinema front, there’s also Sebastian Schipper’s heist-gone-wrong thriller Victoria, which, unlike Birdman, actually is done in one single epic-length take.

“Three’s a trend,” the popular journalism maxim goes, and certainly, film critic Robbie Collin noticed. His recent Telegraph article, tied to the U.K. release of Victoria, notes many of the examples cited above and many more from the past: from as old as Alfred Hitchcock’s 1948 long-take experiment Rope and Orson Welles’s opening time bomb in Touch of Evil (1958) (the height of the form, Collin opines), to more recent examples like Martin Scorsese’s famous Copacabana tracking shot in Goodfellas (1990) and Alexander Sokurov’s digital single-shot Russian Ark (2001).

In tracing the history of the long take, though, one could go even further than 1948, all the way to the beginning years of cinema around the turn of the 20th century. After all, technically, there are little to no cuts in early Lumière Brothers films like Arrival of a Train at La Ciotat (1896) and Thomas Edison films like Electrocuting an Elephant (1903)—but then, this budding new medium known as motion pictures was only getting its sprockets wet then, and filmmakers were more interested in documentation with the new medium than with art. Only with the arrival of artists like George Méliès and D.W. Griffith would the possibilities of editing for storytelling and expressive purposes find its earliest form.

The medium would only ascend from there—especially if we view it through the realism-obsessed prism of French film critic André Bazin. For Bazin, the height of cinematic possibility came not so much with Sergei Eisenstein’s theories of montage—which emphasized the value of editing for expressive purposes—but with Jean Renoir’s and later Orson Welles’s full embrace of deep focus and longer takes to give the spectator more of a choice than, he argues, was often the case under Eisenstein, Griffith, Erich von Stroheim, F.W. Murnau, and other stalwarts of silent cinema. More than just making the spectator a more active participant in the unfolding drama, though, such techniques offered a much closer approximation to reality as we all perceive it, Bazin argued—a technical and dialectical revolution that would help fuel a whole movement: Italian neorealism in the mid-1940s.

If Bazin were still alive today, perhaps he would have embraced some of the international filmmakers—Taiwanese directors like Hou Hsiao-hsien and Tsai Ming-liang, Romanians like Cristi Puiu, Corneliu Porumboiu and Cristian Mungiu, and others—who make long takes and deep focus the bedrock of their style. Between Italian neorealism and the present day, there were also filmmakers like Andrei Tarkovsky, Michael Snow, Chantal Akerman, Theo Angelopoulos, Béla Tarr, and many others who played with the effects of duration within fictional constructs. Of course, Bazin’s vision of cinema is but one view—and even within that view, there are exceptions and complications.

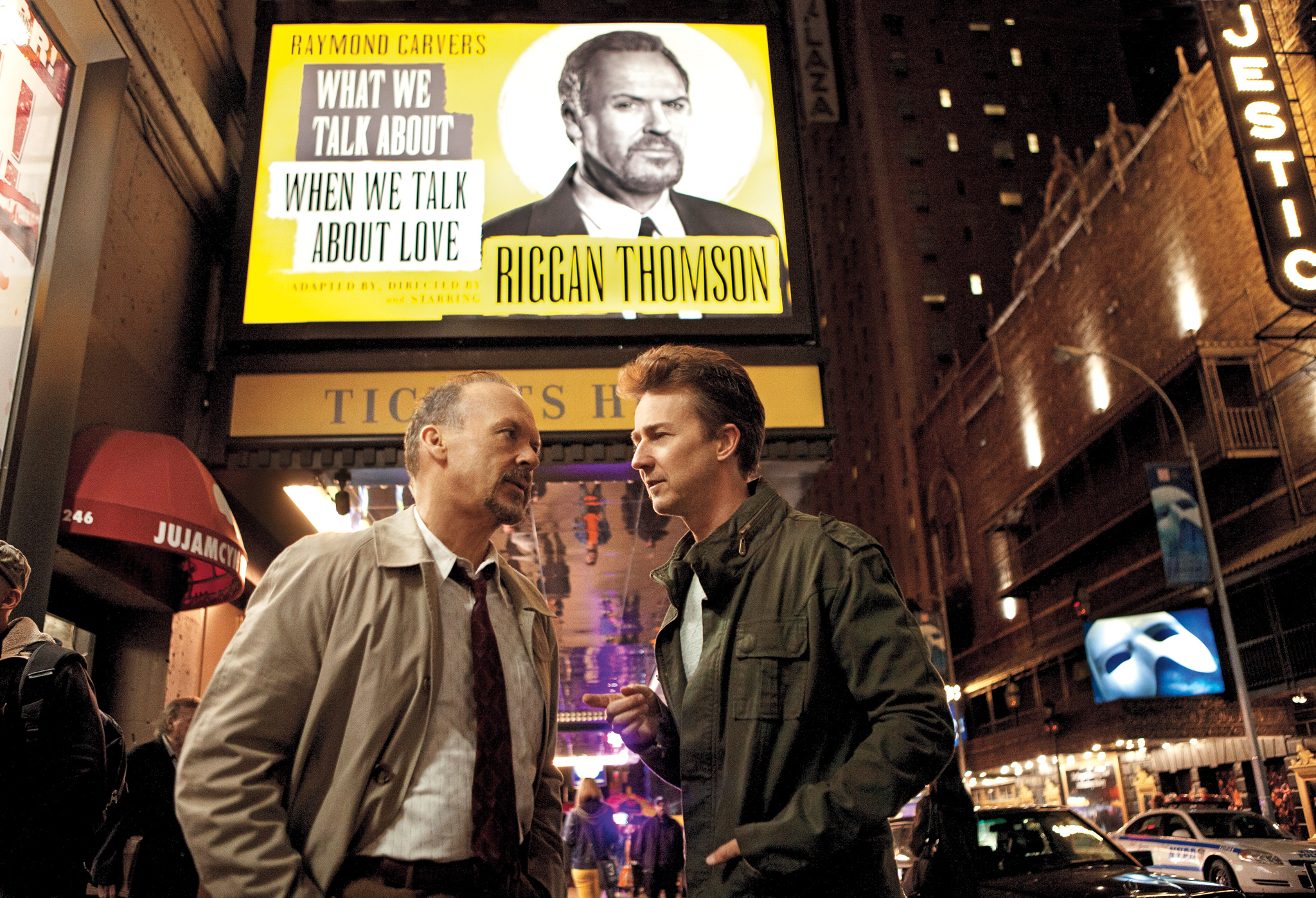

Bazin may have advocated for a cinema that veered toward a depiction of “objective reality,” but not every film that adopts such an aesthetic is interested in reality per se. That was one of the conceptually intriguing aspects of Iñárritu’s formal gambit in Birdman: This backstage comedy-drama dared to adopt an ostensibly “realistic” technique in the service of blurring the lines between reality and fantasy, with the film weaving in and out of what could be protagonist Riggan Thomson’s (Michael Keaton) self-absorbed consciousness. If Bazin prized ambiguity in cinema—one reason he advocated for the sense of spectatorial choice offered by long takes and deep focus—Birdman swims throughout in a sense of ambiguity as to what’s real and what’s not.

Neither reality nor ambiguity is much in evidence in Russian Ark, in which, through one sinuous 87-minute take, Alexander Sokurov weaves through not only the many rooms of the Russian Hermitage, but many different eras in a continuous flow of history and memory. Watching the film, few would argue that Sokurov’s choice to shoot it all in one elaborate take makes it look more “real.” This particular case, though, is made even more complicated by Sokurov’s extensive digital post-production tinkering, with many objects removed, shots reframed, focus changes digitally added, and so on. Bazin lived at a time when special effects had to be achieved as much in front of the camera as possible; he could not have anticipated the limitless possibilities of the manipulation of reality afforded by digital techniques, throwing a further wrench into his belief in the superiority of “objective reality.”

But then, not all films that make frequent use of long takes without the safety net of digital manipulation in post-production can necessarily be said to be “realistic” in the strictest sense. Andrei Tarkovsky, in his infinite patience as a filmmaker, regularly indulged in lengthy takes, but it’s debatable whether the technique inherently enhances the reality of, say, the many scenes of contemplation in his science-fiction dreamscapes Solaris and Stalker. If anything, the longer we find ourselves immersed in his surreal images, the more dreamlike they become. Tsai Ming-liang’s films offer another fascinating case: The sense of realism in his long takes do little to ameliorate the outlandish surrealism of films like The Hole and The Wayward Cloud; his lack of interest in conventional psychologizing of eccentric human behavior only adds to the playful sense of whimsy.

In the end, it all depends on how the long take—by its very nature a showy technique, since most of us are accustomed to conventional shooting and editing patterns in storytelling—is used. Long takes can genuinely immerse us in the reality of an environment, as Béla Tarr and Hou Hsiao-hsien regularly proved in their films. Or they can allow for a wider variety of incident and emotion, as Alfonso Cuarón’s rollercoaster of an opening 15-minute shot in Gravity brilliantly demonstrated. All the technical gimmickry in the world, though, won’t necessarily mean much if it’s ultimately supporting middling substance. Dennis Hauck might have structured Too Late as a series of five long takes, but the technical bravura is hardly enough to counteract the third-rate Tarantino-isms contained in those shots. Not even Iñárritu was able to make lightning strike twice with The Revenant; without any of the interesting play with reality and illusion to animate his use of long takes, we’re left with nothing more than the spectacle of a self-serious director flexing his muscles to try to lift glorified B-movie material to the realm of macho myth. But considering how ubiquitous the handheld, quick-cut, shaky-cam style is in mainstream action movies—an approach that, far from immersing us in the physical and/or emotional immediacy of a scene, usually has the effect of distracting us from it—maybe the return of the long take should be welcomed with open arms.

2 thoughts on “Why Long-Take Cinema Should Do More Than Experiment”

“Not even Iñárritu was able to make lightning strike twice with The Revenant; without any of the interesting play with reality and illusion to animate his use of long takes, we’re left with nothing more than the spectacle of a self-serious director flexing his muscles to try to lift glorified B-movie material to the realm of macho myth.”

Spot on.

Pingback: Carousel, April 14 – Tamara Dunn