The English have Shakespeare, the French have Molière, the Russians have Chekhov, the Argentines have Borges, but the Western is ours.

– Robert Duvall

The Western may be the only art form entirely specific to a time and place. Though literature of the Old West was born out of lowly dime novels and pulp magazines, it was cinema that etched its images in our minds. Ten gallon hats and six shooters. Jeans and boots. Saddled horses in the midst of a cattle drive. Tumbleweed rolling through a barren midwestern landscape with roaming settlers searching for their manifest destiny. All of these evoke a world that was first envisioned by film. Movies immortalised the cowboy.

There have been many great Westerns through the years, most of them focusing on legendary characters or the stories which they inhabit. But for one film, these elements do not serve the traditional purpose of advancing a plot or resolving a conflict. They instead serve as a romantic tribute to the archetype of the Old West. Once Upon a Time in the West is the mythic Western; an ode to the end of its era.

The film was directed by Sergio Leone, a longtime veteran of the Italian film industry who saw the commercial potential (oddly enough through Akira Kurosawa’s Yojimbo) of making European versions of the Western. Through his Dollars trilogy (A Fistful of Dollars; For a Few Dollars More; The Good, the Bad and the Ugly), he remade the Old West as a gritty, primal and instinctive world filled with anti-heroes, edgy characters and cold-hearted villains, free from the clean-cut moralism that pervaded its American predecessors. A new Western sensibility was born, one that swung between an almost playful visceral energy to a crackling sense of danger.

But apart from the growing stakes and excitement in each successive film of Leone’s trilogy, there is evidence of a growing sensitivity and complexity to his work. Moments of poignancy are given more and more weight. A more languid sense of pacing develops. Panoramic vistas figure more prominently. His denouement draw themselves out more lengthily and become more operatic with each musical score. Visual effects become trickier. And thematic darlings are kept around as long as possible before they are killed off. All of these eventually culminate into Leone’s supremely personal statement in Once Upon a Time in the West.

The film’s most distinguishing aspect is its music, which soars hauntingly in the film’s most memorable scenes. The great composer Ennio Morricone, Leone’s longtime collaborator, infuses the film with its solemn identity. Whereas the music for the Dollars trilogy was marked by its impish energy, Once Upon a Time in the West is by turns elegiac, grim and wistful. It is its grave tempo that allows its scenes to play out more patiently than its predecessors. His incredible use of music is but one facet of his aural prowess, as he displays an uncanny sense of imagery with sound, as evidenced in the film’s first two sequences, involving a massacre at a train station and another at a secluded family outpost.

Sergio Leone’s films have been known to showcase the human face. In his Dollars trilogy, he uses actors with hard edged and cracked features to reflect the barrenness and harsh environments in which their characters lived in. But in Once Upon a Time in the West, the physical edginess gives way to a grace and beauty not witnessed before.

Consider Claudia Cardinale who heralded an earthier sensuality compared to the primped-up beauties of past Westerns. Her looks at first are used to tantalize, but later transforms into a symbol of matriarchal love. Also notice how her personal beauty is juxtaposed with long lost glories and natural landscapes.

There’s also the masterstroke of casting Henry Fonda as the film’s villain. Once the ideal man Leone wished to cast as the man with no name, he gamely portrays a terrifying gang boss, with those baby blue eyes conveying a steely cold reserve as opposed to the paragon of virtue he was renowned for in Hollywood.

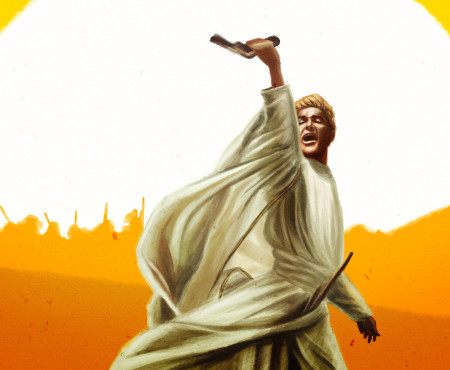

And of course, there is Charles Bronson, whom we all know as famed vigilante of the Death Wish movies. Here he is the Leone’s embodiment of the cowboy. Taciturn, patient, unaffected and stealthily dangerous. But beneath that intimidating presence, he somehow conveys an honor, intelligence and grace even in moments of pure stillness. Clint Eastwood once said that Gary Cooper wasn’t afraid to do nothing. Neither was Bronson.

With this triumvirate of Jill McBain (Cardinale), Frank (Fonda), and Harmonica (Bronson), Once Upon a Time in the West becomes a model of cinematic iconography; a soulful death knell mourning the end of an era and of a way of life long gone.

“Set against the backdrop of the encroaching railroad, which promises to bring civilization to this unruly, harsh country. And with progress, the coal-devouring locomotives also bring death—death for the American West’s unspoiled beauty, death for an uncomplicated rugged individualism, and death to the cowboy, who has no place in the newfangled modern world of corporate villainy and commerce.”

2 thoughts on “History of Film: “Once Upon a Time in the West””

Pingback: SR Geek Picks: Sergio Leone Tribute, ‘Star Wars’ Babies & More

Who did the art work? Because if it were to maybe end up as my Facebook cover image I would like to give credit where credit is due.