When one thinks of Alfred Hitchcock, what’s the first film that comes to mind? Certainly, the corpulent master crafted many iconic images, and just as many films. It’s hard to nail down maybe one specific image that defines Hitchcock, but if I had to pick one film that perfectly encapsulates his mission statement as artist, it’d be Psycho. Impeccably crafted in every way, it is the ultimate showcase for how the master showed us everything: by showing us nothing at all.

When a young woman steals a large sum of money from her boss’ cash deposit box, she skips town and embarks on a road trip to nowhere in search of escape from her destitute existence. One police encounter and a swapped vehicle later, she finds herself taking shelter from a massive storm in the ominous Bates Motel.

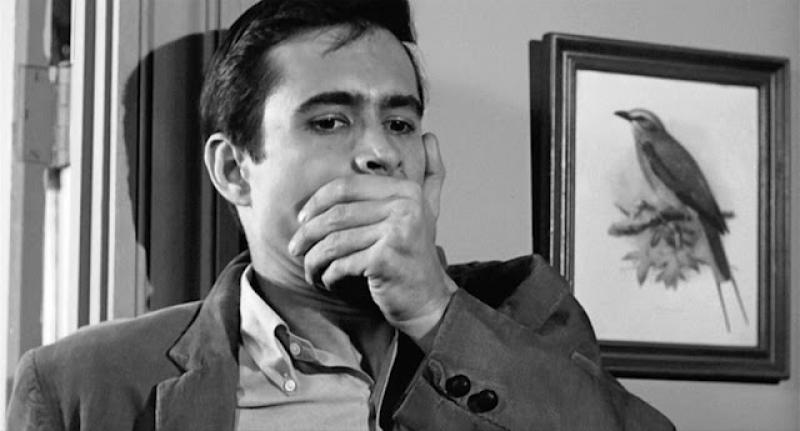

Our introduction to Norman Bates brings many of the film’s most prominent themes to the forefront. As Norman relates tales of his mother’s woeful condition to Marion, the undercurrent of guilt and jealousy begins to simmer, coming to a boil when Marion speaks out of turn. There’s just something not right about Norman or Marion, and both and smell it on one another. It’s here that we get the first taste of the more sinister happenings at the Bates Motel, leading us, of course, to the legendary shower scene.

Mythologized by film lovers, historians, and critics, it’s the scene that more or less put Hitchcock on the map, horrifying studio executives and thrilling audiences en masse. The scene’s ability to both convey terror and be sexually provocative is nothing short of astonishing, potentially paving the way for nearly every slasher film in history. The close-up shots, the frantic editing, and Bernard Herrmann’s iconic score all evoke a genuine sense of madness and terror, down to the final moment as Marion quite literally watches her life swirl down the drain.

It’s no wonder, then, that numerous legends about the shoot emerged. All manner of myths, ranging from whether or not Janet Leigh had a body double to claims from Saul Bass that he himself directed the shower scene. The latter was dismissed by multiple sources, and honestly made very little sense at the end of the day; Hitchcock, being the perfectionist he was, was unlikely to have allowed such a pivotal scene be directed by anyone else.

Htichcock had shot films in color prior to Psycho, but reversed that trend and shot Psycho in black and white. While not necessarily against the grain at the time (contemporary films like Billy Wilder’s The Apartment were also shot without color), the aesthetic choice does not go unnoticed. The stark contrasts and deep shadows prove the perfect backdrop for this tale of guilt and madness. As Marion’s own guilt and doubts over her theft loom, so to do the storms and shadows rolling over the hills, eventually engulfing her in their deathly embrace. It’s only as the film progresses onward that Norman’s own guilt over the fate of his mother goes on to consume him.

Indeed, the second half of the film is far less memorable (or at least less discussed) than everything leading up to the shower scene. Perhaps it’s because none of the actors make as much of an impression as Janet Leigh, but there’s no denying that once the initial murder has taken place, there’s something slightly deflated about the film, as least in the investigatory sense. Instead, Hitchcock’s true strengths towards the finale lie in the descent into madness, as more and more of Norman Bates’ true identity is revealed. We see rakes in the hardware store loom like talons over Lila’s head, not-so-subtly hinting at the encroaching darkness that surrounds the lives of our characters, and Norman’s mother is consistently only seen in silhouette, foreshadowing the horrific reveal of her corpse, backlit in all its decrepit glory.

It’s a shame that either Hitchcock or the studio executives didn’t trust audiences to understand what is otherwise a rather straightforward villain, thus allowing Dr. Exposition to grace us with his blundering explanation of everything we’ve already seen and presumably comprehended. It’s a bizarre scene that threatens to deflate the entire film, but luckily every moment that proceeds it is so stunningly crafted that it can’t be undone by a momentary lapse in creative judgment.

As an example of Old Hollywood filmmaking, Psycho was scandalous. As a piece of pure cinema, it’s sensational. Sexually charged and deceptively “violent,” it’s the kind of film that has been studied for decades, and will continue to be studied for many more decades to come. After all, you don’t get to lay claim to the greatest horror scream in cinema without having earned it.