In spotlighting Ingmar Bergman’s magnum opus Fanny and Alexander as one of the great films of the 1980s, one cannot help but marvel at how out of step with the ‘80s it is, and least of all for its period setting in the early years of the 20th century. In a decade where special effects ramped up considerably and the first CGI dotted screens came to fruition, Bergman’s film rhapsodizes in the creaky obsolescence of stage trickery, of false backgrounds and perfectly arranged lights and minute blocking.

Video technology provided auteurs like Jean-Luc Godard a whole new prism through which to view cinema, while the music video format was shaping the skills of the next generation of mainstream filmmakers. Fanny and Alexander, stands proudly outside such technological and popular developments, its classical style and theatrical mise-en-scène harking back to a day of cinema that may actually precede cinema.

What it shares with the best films of the decade, however, is its ability to subtly draw a critique from optimistic surroundings. Compared to the dour films of the ’70s that searched for meaning in post-’68 Europe and post-Nixon America, Fanny and Alexander commences in rapture, the blood-red walls that made the house in Bergman’s own Cries and Whispers so foreboding now shot through with Yuletide cheer. But as the libations die down and Christmas Eve slurs into Christmas morning, family gossip begins to dribble from the drunken, tired mouths of the wealthy Ekdahl family, revealing personal failures and hidden shames beneath the surface. Even so, the portrait Bergman paints of the Ekdahls is one of warmth, playful and reflective in equal measure.

One shot, however, points toward the gradual dissolution of joy. Alexander (Bertil Guve), the co-protagonist and child of the Ekdahl’s eldest son, finds a mouse caught in a trap as he plays around his grandmother’s house. Alexander opens one end of the cage, but the mouse does not dart out, instead hanging half-inside the box as if suddenly afraid to emerge from its confines. This becomes the dominant metaphor of the film, from the servants who balk at being treated as equals (per Ekdahl tradition, Christmas dinner is enjoyed by master and maid alike at the same table) to the desperate, albeit cautious, search for escape when Fanny (Pernilla Allwin) and Alexander find themselves under the roof of a tyrannical bishop when their mother, Emilie, remarries following their father’s sudden death.

Gradually, Bergman induces a sense of discomfort, then outright horror, that fits this seeming aberration of goodwill into his somber corpus. The first act plays heavily on symmetrical composition, but the camera’s reflection of good staging calls to mind the unsettling centering of Stanley Kubrick’s work, in which the frame is so tidy as to stress its unrealness. Far worse than the too-perfectly ordered clutter of the Ekdahl house, however, is the ascetic emptiness of the bishop’s house. Centered frames become surreal, but the decentered, triangulated arrangements of the white, cold house become a prison as the bishop physically and psychologically tortures his new family.

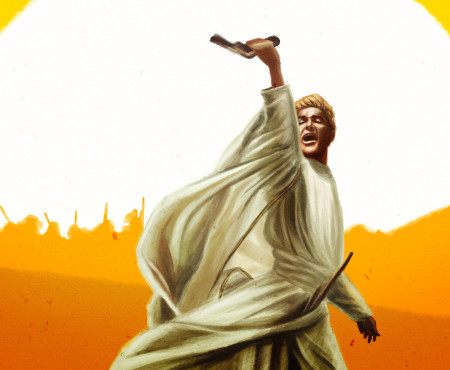

The only solace lies in Alexander’s imagination, which powers the film and, with so many frames filmed through makeshift proscenia, may be the movie’s root perspective. A mechanized, life-sized Death drags a scythe on the ground of the Ekdahl home at the start of the film, a great theatrical prop that the boy observes curiously. Soon, however, the boy is conjuring his own dead, with visions of his father and other ghosts emanating and gaining strength from his imagination. Alexander’s imagination thus becomes the vehicle of his liberation as much as the involvement of corporeal friends and family, a clear link between the film and Bergman’s own, harsh upbringing under his religious father.

If Fanny and Alexander can be said to truly fit into the tone of ‘80s cinema, it’s in the hope it extracts from its disquiet. Even when the Ekdahls reassert themselves and find an internal equilibrium, Alexander faces the possibility of being haunted by the bishop forever. But this can also inspire the boy and bolster his imagination as he looks for ways to overcome the demon, a note of sad but poignant perseverance common to the decade’s best films. Do the Right Thing ends with a tacitly reaffirmed bond between two friends nearly torn apart by racial violence; The Green Ray finds a path to emotional stability in its protagonist’s breakdown; even Godard’s King Lear, with its despairing view of lost art, finds vigor in its breathtaking assembly of image and sound. Fanny and Alexander belongs in their company, a sprawling but tightly controlled epic that takes place behind closed doors but opens up worlds inside of them.

One thought on “History of Film: Ingmar Bergman’s ‘Fanny and Alexander’”

Definitely one of my all-time favorite films by Bergman. I still want to see the long TV version of the film. I just love that family and felt for the kids when they have to move to that awful new home.