I. A traumatized child cries against a wall. A woman wails in defiant protest. These images occur in the same sequence in The Battle of Algiers when the National Liberation Front (FLN) wage an eight-day general strike across Algeria in active provocation against the French Algerian authorities. While the two images communicate different ideas, both capture director Gillo Pontecorvo’s unique approach for the film.

The first occurs when the French break into the homes of the Algerians in the early hours of the morning to drag them out into the streets. As Ennio Morricone’s jaunty score pulses over the soundtrack, Pontecorvo follows the French as they run through the street, kick open doors, and shoot indiscriminately into the sky in order to intimidate the Algerian populace. He tracks different floors of various open apartment complexes while paratroops haul shop owners out of their homes with their wives clinging to the hem of their clothes. In one scene, a man and a woman are pulled from their home while their child cries at their feet, dangerously close to being trampled by the authorities. Luckily, one soldier pulls the child away from the chaos, and soon his parents are carried into the shadows. Pontecorvo ends the scene on the image of the child, face against the corner of the doorway, turning his head towards the confusion, crying out in terror.

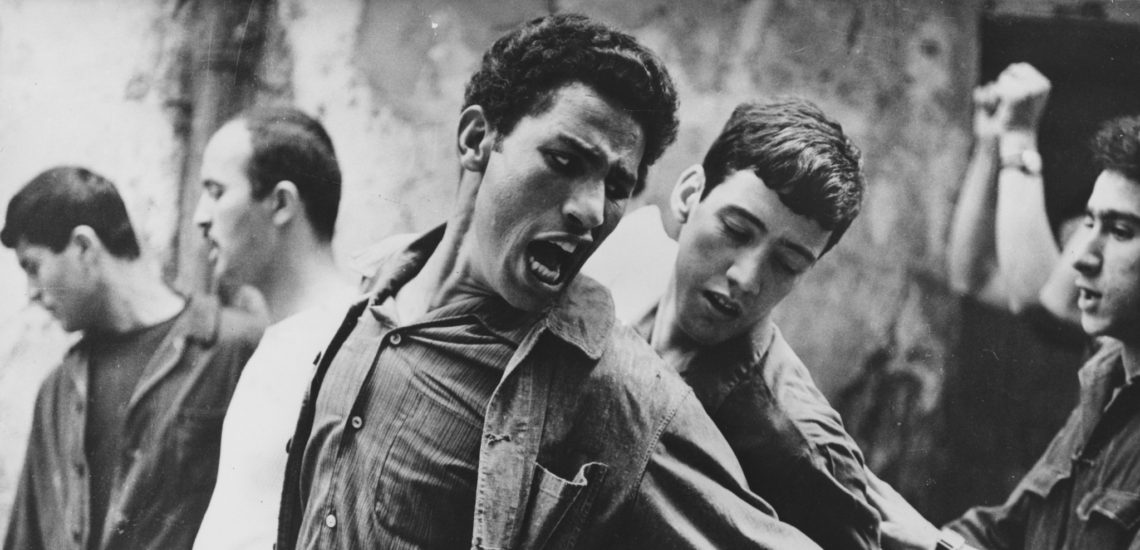

The second image appears on the sixth day of the strike, with the Algerians in the streets being hassled by the French. A French soldier blares over a loudspeaker, “The FLN wants to starve you and condemn you to poverty. The FLN wants to stop you from working. People of the Casbah, France is your motherland.” But when the soldier puts the mic down, street urchin and FLN messenger Petit Omar (Mohamed Ben Kassen) surreptitiously steals it to deliver the exact opposite message: “The FLN tells you not to be afraid. Don’t worry, we’re winning. The FLN is on your side.” At this point, the crowd bursts into sparse chants of “long live Algeria,” and Pontecorvo closes in on a woman who lets out a wail, later described by the voiceover as an “unintelligible and frightening rhythmic cry.”

With unparalleled immediacy and without an ounce of sentimentality, Pontecorvo illustrates the destructive effects of war and the inspirational voice of the oppressed. By juxtaposing the devastation with the protests of the persecuted, he captures the unsparing amorality of war and the fierce morality of actual conflict, and the uncomfortable area that lies in between justifiable cause and damaging effect. The Battle of Algiers endures for many reasons—continual political relevancy and formal bravado are two the most cited—but the one that stands out is its brutal commitment to the painful nuances. Nothing is simple or easy, especially when it comes to war, and Pontecorvo embraces that with aplomb.

II. Fifty years after its premiere at the Venice Film Festival, where it won the Golden Lion, it’s difficult to say anything new about The Battle of Algiers. Pored over countless times by critics, journalists, and academics alike, the film’s political content and documentary-style realism has been embraced by insurrectionist movements and colonial invaders alike. Everyone from the Black Panthers to the Pentagon circa-2003 has studied the film for its guerrilla war and occupation tactics, respectively. Pontecorvo’s essential fair-mindedness, while still fundamentally siding with the Algerian revolutionaries, channeled into Algiers’ neorealist style makes it accessible to those on both sides of the ideological divide. Colonel Mathieu’s (Jean Martin) reserved pragmatism and Ali La Pointe’s (Brahim Haggiag) rebellious fervor have captured the hearts and minds of generations of cinephiles and political scientists, both embodying the ideal profiles of the state and the insurgent (or colonialist oppressor and terrorist, depending on your politics).

While all of those elements are worthy of discussion and praise, it’s Pontecorvo and Franco Solinas’ script, specifically its ability to avoid psychologizing its subjects as a gateway to emotional connection, that feels like Algiers’ most “radical” quality, at least in narrative terms. In its initial development, the film was supposed to star Paul Newman as a magazine reporter assigned to cover France’s occupation in the Casbah. His journey from distanced objectivity to social consciousness was to dominate the film while the plight of the Algerian people would inevitably be sidelined as a secondary concern. “You can understand the logic,” says Peter Matthews in his Criterion essay. “A ‘difficult’ subject demands the warranty of a box-office name to pacify backers and entice a wide audience, who will hopefully learn a thing or two.”

Thankfully, FLN representative Salah Baazi posed a critique of the initial script, and after Pontecorvo and Solinas traveled to Algiers to interview eyewitnesses and study the conflict in depth, they decided on a different narrative strategy, one that would treat the conflict with the expansiveness it deserved. “Psychology was a red herring,” continued Matthews. “The Algerians had, after all, waged a political campaign in response to a collective experience of injustice. The revised film would chronicle nothing less than the battle of an entire nation for selfhood.” Algiers focuses on many subjects—Mathieu and la Pointe, but also top FLN leaders El-Hadi Jafar (Saadi Yacef) and Larbi Ben M’hidi, and in one long sequence, three women guerrillas who plant bombs in crowded places—but all are treated as a small representative of a larger political battle, not as “protagonists” with neat emotional arcs or easily accessible psychologies (hero, villain, sidekick, etc.) The audience isn’t supposed to identify with a human being, but rather a cause, something that feels downright experimental relative to today’s commercial entertainment.

The creative choice to eschew any psychological involvement on the part of the audience heavily contributes to Algiers’ political and emotional nuance, as it frees Pontecorvo to examine the Algerian War of Independence in terms of ideas without saddling them to contrived dramatic situations. He rapidly jumps around between characters and events, mainly capturing the weight of the war—physical damage, national fear, the faces of the oppressed, the single-minded determinism of both the Algerian rebels and the French army as collective units. It allows the film to consider complicated positions that don’t neatly fit into standard binary conceptions of war: the moral passion of the Algerians in the face of colonialist oppression and their violent terrorism that results in the deaths of innocents; Mathieu’s superficial sincerity regarding the targeting of a small minority of Algerians and the French Army’s widespread intimidation tactics against the entire civilian populace; the cold-blooded murder of soldiers and the vile torture of insurgents; and so on and so forth.

But perhaps Pontecorvo’s greatest achievement in Algiers is the way he commits to depicting the grey areas without excusing the colonialism on display. He shows the Algerians’ terrorism unsparingly, but always as a response to the systemic and total subjugation at the hands of the French. Pontecorvo focuses on the hardened faces of the Algerians as they’re constrained and trapped by France, who have stolen their freedom and robbed them of any political or economic status. Algiers never justifies the actual violence, but it illustrates it as the inevitable end of colonialist rule, and the literal history of the Algerian War of Independence backs that thesis up. France’s brutal methods during the War alienated them not just from the Algerian citizens but also from the Metropolitan French, eventually culminating in widespread demonstrations and, ultimately, negotiations for independence. Pontecorvo’s wide-ranging approach never precludes his own morality on display.

III. In the age of ISIS, Trump, and generally state-sanctioned violence, it’s easy to find modern-day parallels with The Battle of Algiers. But though the film functions as a training manual for future rebels and military personnel alike, focusing on the violence alone feels like a disservice to its depiction of hope in the face of seemingly endless dread and horror. The last shot of the film is of a woman taunting soldiers with the Algerian flag, spinning around in circles while waving it over her head. It’s a political dance, one that spits in the face of fear and despondency, one that actively celebrates defiance. While the traumatized child and the wailing woman cannot exist independently, the latter should be the one that’s seared in the memory of viewers, if only to pass it onto future generations in perilous times.

One thought on “Rock the Casbah: “The Battle of Algiers” Turns 50”

It’s one of these films that hasn’t just gotten better since its release but it feels so relevant to the state of the world today. It was as if it was showing us the future as it is going to happen and it is fucking smacked on.