A drumroll immediately marks the difference between Aliens and its predecessor, Alien. Jerry Goldsmith’s music for the opening credits of Ridley Scott’s 1979 original is spooky and foreboding, all skittering strings, quietly wandering wind, and synthesizer lines—a moodiness perfectly in keeping with the haunted-house atmosphere of the film that follows. James Horner’s music for the opening credits of James Cameron’s follow-up—celebrating its 30th anniversary today—initially sounds like more of the same…until a military-style drumroll is heard, seemingly from a distance, the motif recurring again, louder and closer with each repetition, with the music crescendoing to an ear-blasting fever pitch as the film’s title finally, fully appears onscreen.

That drumroll is, to be sure, a similar harbinger of the film to come: a sci-fi picture that, at least after an hour of patient set-up, veers more toward action than the slow-burning slasher-movie-like horrors of the original. But the initial faraway nature of that first drumroll is also thematically significant. If a military drumroll could be said to evoke a macho sensibility, then a muffled, distant version of the same suggests a testosterone-based perspective recalled in hushed, regretful tones—machismo made petty and small.

That promise of a subversive attitude toward machismo is something Cameron’s film eventually fulfills, in its own muscular way. Instead of the corporate grunts who made up the cast of Alien, Aliens is populated mostly by Marines—and many of them are hardly shy about indulging in locker-room banter, impromptu dick-measuring competitions, and excitement about hardware. (It’s not entirely a boy’s club in this case, but even the two female Marines—Private Vazquez (Jenette Goldstein) and Corporal Ferro (Colette Hiller)—are characterized as mannish, completely at home in this otherwise testosterone-fueled environment.) The most proudly macho of the soldiers is Private Hudson (Bill Paxton), who comes across as an enthusiastic teenage boy who gets off on displays of his might.

Early in the film, though, Private Hudson is also seen at the receiving end of a dangerous trick courtesy of the team’s resident android, Bishop (Lance Henriksen), in which he moves a knife with increasing rapidity in between each of his fingers. That instance of jokey victimization is just a prelude to the way he becomes the film’s most comic and poignant encapsulation of the cutting down of masculinity to pipsqueak size that transpires when the crew finds themselves menaced by the aliens on planet LV-426. There’s a reason why Hudson’s “game over, man” line has become both an iconic moment and an easy source of parody: Paxton delivers it like a panicked, drunken fratboy who is horrified to discover he’s in way over his head, but the comic tinge of his delivery is offset by the hopelessness felt in the moment. All those guns and ammo those Marines lovingly fetishized earlier have proven to be useless in the face of a remorseless band of extraterrestrial enemies. These aliens have exposed at least some of the Marines for the cowards they truly are.

Standing in contrast to the Marines’ unabashed machismo is the film’s hero, Ellen Ripley (Sigourney Weaver), whose warmth and vulnerability even as she finds herself forced to take charge and arm herself with weapons offers an ideal middle ground, suggesting a machismo gratifyingly leavened by such qualities as empathy. Because of her previous horrifying experiences in the original Alien, she is, naturally, the only one who even bothers to think of all the families who live on the now-colonized LV-426; certainly, the corporate bigwigs surrounding her in Aliens—with Burke (Paul Reiser), who accompanies Ripley and the Marines on their mission, proving to be the slimiest—seem to care less about those inhabitants than about maintaining certain economic bottom lines. But it’s the discovery of Newt (Carrie Henn), a plucky young girl who miraculously managed to survive the aliens’ attack on the inhabitants of LV-426, that fully unlocks Ripley’s sensitive side, her maternal instinct fully taking over. (Weaver actually garnered an Oscar nomination for her performance in this film, which, beyond validating her excellence in the role, perhaps suggests just how unusual a protagonist like Ripley was in genre films of the time.)

Ripley’s maternal instinct finds a match in that of the mother alien who has given birth to all the aliens terrorizing her and the Marines. This thread is something Cameron is merely amplifying from Ridley Scott’s original. If Alien could be interpreted as an allegory of the terrors of pregnancy—with H.R Giger’s alien design taking the form of a vagina dentata, aliens being violently birthed by puncturing the skin and killing its hosts, and the crew addressing their all-knowing computer as “Mother,” among other symbols—then Aliens elaborates more fully on the feelings inspired after a mother gives birth. Whether Cameron intended it or not, there’s a hint of emotional ambiguity in the moment where Ripley discovers the mother alien’s nest: It’s one mother against another, and despite Ripley being the hero and the mother alien being the villain, both are driven by the same primal desire to protect their young. On the one hand, Ripley’s torching of all the eggs is a necessary act of heroism; from the mother alien’s perspective, however, it’s a heartbreaking atrocity.

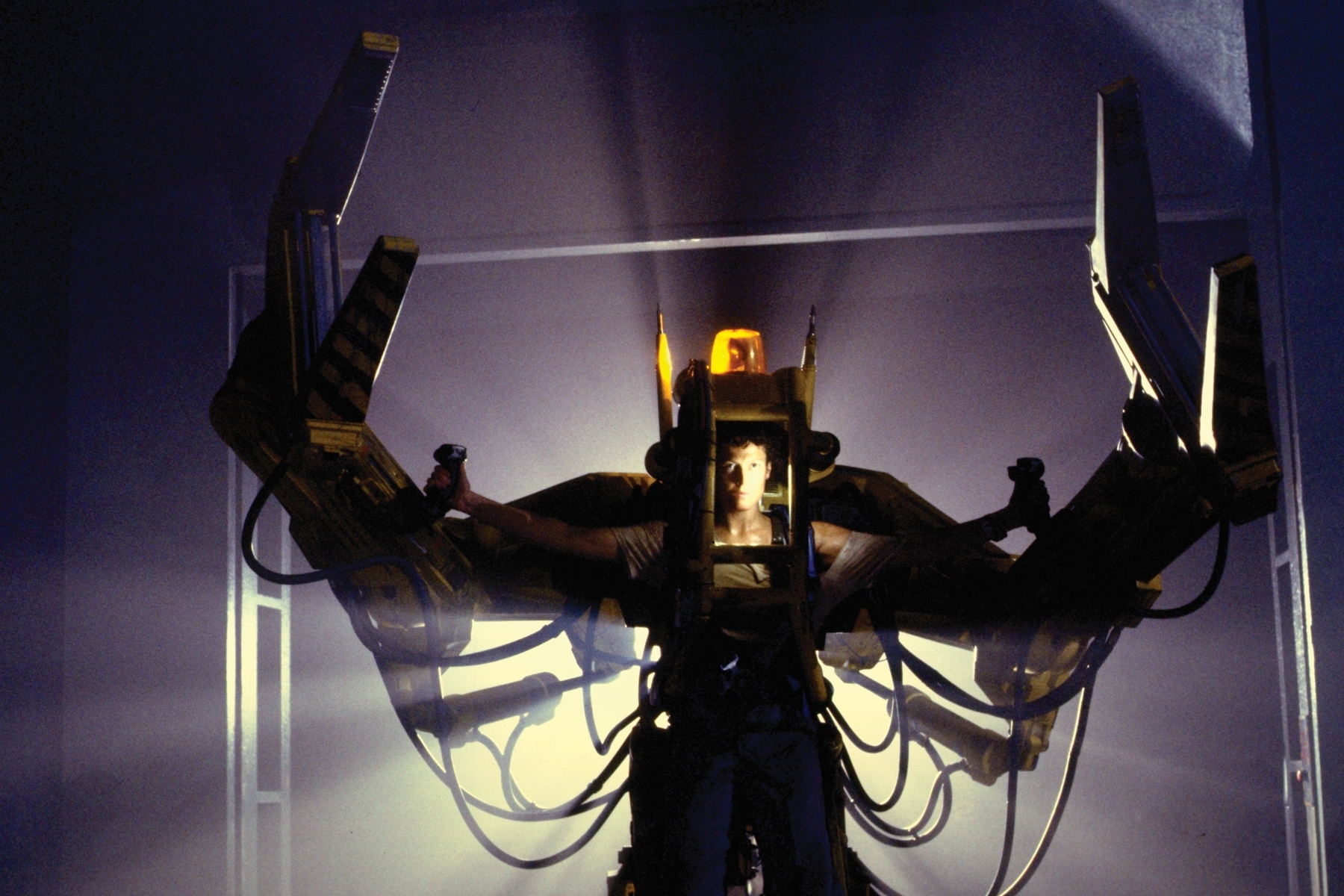

Still, Aliens is, in the end, a 1980s action movie, so perhaps it’s inevitable that even Ripley gets one of those climactic cheesy one-liners as she embarks on her final mano-a-mano showdown with the queen alien—“Get away from her, you bitch!”—complete with dramatic dolly shot closing in on her face as she utters those triumphant words. Compared to the relative sobriety and concern Ripley shows throughout the rest of the film, this line seems slightly disappointing—Cameron pandering to the kind of mindless bloodlust that was in vogue with the popular Arnold Schwarzenegger and Sylvester Stallone action epics of the time. But then, Aliens’ obsession with weapons, hardware, and machismo all scream the ’80s as well, in a decade that was heartily marked by all three of those qualities, both in movies and in the wider world. What Cameron adds to the table, in still-thrilling style, is just enough self-awareness to offer a female heroine that suggests a different path for the genre, one that would pave the way for the Jason Bournes and Imperator Furiosas of today.

One thought on “The Subversive Machismo of “Aliens””

For me, this is the best film of the series as it is just full-on badass where you didn’t just have some guys kick ass but also a couple of ladies in Vasquez and most of all, Ripley who gets to really kick some fuckin’ ass in that film.