There is a particular art to a final shot. Every shot in a film is important — it’s one that didn’t end up on the cutting room floor, so it is inherently significant, though perhaps not extraordinary. Any one of these shots can be truly dazzling in any number of limitless ways. But a film’s final shot requires special consideration. How do you want to leave your audience? How can you summarize what you’ve been trying to say, or should you even try? What do you want people to remember?

James Gray’s most recent film, this year’s The Immigrant with Marion Cotillard and Joaquin Phoenix, is a great film for many reasons, but it has been rightfully celebrated for its gorgeous, show-stopping closing shot. Without giving it away, one half of the screen is a mirror, the other a window, and there is so much being said in this one brilliant shot. It’s a shot people will remember, as they consider Ewa’s journey going forward, and the fact that hers is one story among many. It’s such a perfect shot that it got me thinking, so here are some of my favorite final shots, excluding some of cinema’s most celebrated ones like those in 2001: A Space Odyssey, The Shining, Psycho and Casablanca.

Obviously, some spoilers follow.

10.) The Wolf of Wall Street (Martin Scorsese, 2013)

One of the most intense raging debates in film last year was over whether the behavior of Jordan Belfort and others as depicted in Martin Scorsese’s The Wolf of Wall Street is glorification or castigation. I don’t see why it can’t be a little of both, but it wasn’t until the film’s final shot that I understood, that the entire three-hour film came into focus and Scorsese’s vision was made manifest. In the somewhat surreal final scene, the real Belfort introduces Leonardo DiCaprio as Belfort, who then tries to get audience members to sell him a pen. The camera pans up to stare at Belfort’s audience, mirroring the movie audience. Look at yourselves, the camera is saying. After everything you’ve just seen, you’re still sitting in Belfort’s audience. Captivated.

9.) The Descent (Neil Marshall, 2006)

Plenty of horror films have twist endings, final shots where the supposedly dead killer or monster moves, or deeply cynical send-offs. The Descent has elements of these things, but it adds a wallop of emotion and impressive composition. After leaving her friend for dead, Sarah (Shauna Macdonald) crawls on a suspiciously cinematic-looking pile of bones to escape the caves and drives away. The friend pops up for a scare (which is where the American cut ends), then we’re back in the cave. Sarah gets up to stare at her daughter, who was murdered, sitting with a birthday cake, and we realize she’s gone to a happy place as the the camera pans out, the daughter disappears, and the creatures close in from all sides. It’s devastating, heartbreaking and uniquely effective.

8.) Stranger Than Paradise (Jim Jarmusch, 1984)

This is a small film in many ways, including its plot, in which not much really happens. It’s what makes every moment count, and the final shot encaptures that best. Earlier, Eddie (Richard Edson) says the film’s most memorable line, “You know it’s funny. You come to someplace new, and everything looks just the same.” What could better sum that up than ending in a motel room, the epitome of standardized blandness? Everywhere is a wasteland, and we’re all alone in them, so why not embrace the emptiness?

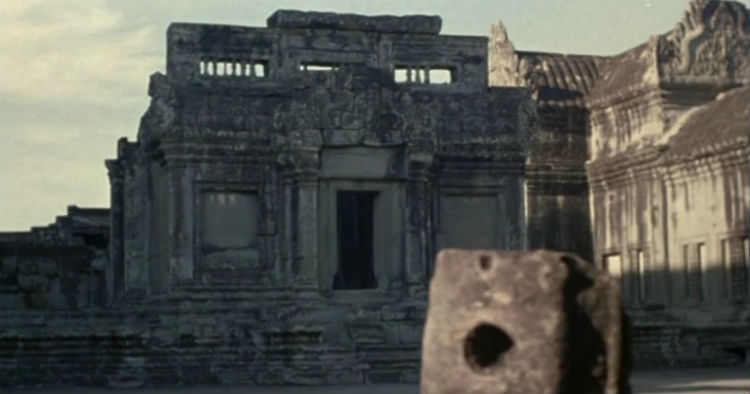

7.) In the Mood for Love (Wong Kar-wai, 2001)

This film’s original Chinese title, 花樣年華, refers to the fleeting nature of youth and love, which speaks to the tragic love story of Chow (Tony Leung) and Su (Maggie Cheung). They each have spouses, and once they start to see each other more, the socially conservative Hong Kong in the 1960s keeps them from further exploring their romance. After that, they just miss each other in a series of close-calls that would be comical if they weren’t so devastating. At one point, Chow tells a story about how in the past if you had a secret that cannot be shared, you would make a hollow in a tree, whisper your secret, and cover it with mud. In the final scene, he whispers into a hollow in a ruined monastery’s wall for quite some time, covers it with mud, an intimacy he and Su never knew together, and walks away. We close on the monastery, and probably cry.

6.) Children of Men (Alfonso Cuarón, 2006)

This beautiful and foggy shot, enriched by its composition, is one that holds both hope and caution. In this future, no children have been born in nearly 20 years, until Kee (Clare-Hope Ashitey) becomes inexplicably pregnant, and Theo (Clive Owen) must get her to safety. To do so, they have to get to the Tomorrow Project, a mysterious group who will ostensibly shelter her. After losing everyone else for this cause and somehow surviving long enough to get her to where the Project’s boat will be, Theo begins to drift away from his wounds, as the boat approaches. Framed as it is, the boat is a symbol of hope and salvation coming for Kee, but the red light on the buoy seems to be a warning that perhaps they aren’t to be trusted, either. Your call.

5.) Sunset Boulevard (Billy Wilder, 1950)

This is one classic final shot that may deserve more praise than it gets. Looking just like Nosferatu, Norma Desmond slithers toward the camera while saying the iconic line, “Mr. DeMille, I’m ready for my close-up.” The tragic story of Norma hits hardest watching today because so many women still end up being washed-up in their middle age because Hollywood still does not value them. Norma couldn’t believe it then, so she lives in a state of constant and deep delusion. We can’t believe it now, either, so the idea that getting older meant accepting irrelevancy in the Golden Age of Hollywood grows ever more poignant each year it continues. By capturing the essence of her delusion in that final shot, director Billy Wilder shows us the tragedy of this reality.

4.) A Serious Man (Joel & Ethan Coen, 2009)

If there’s any last shot more devastatingly cynical than The Descent’s, it’s the one in the Coen brothers’ A Serious Man. Larry Gopnik (Michael Stuhlbarg) tries to be a good person. For God, but also for himself. He spends much of the film wrestling with this, and by the time we reach the film’s end, and after an apparent internal struggle, he decides to change a grade in his own interest. Immediately, he gets a phone call from his doctor, who essentially confirms his worst fears about his X-ray results. Cut to his son, Danny, staring down a massive incoming tornado as his teacher fails to open the emergency shelter. Is this God’s wrath? Over Danny’s shoulder, the tornado looms as Jefferson Airplane’s “Somebody to Love” plays. The film was building to this kind of cosmically tragic moment, but it is still wholly affecting and unnerving.

3.) Magnolia (Paul Thomas Anderson, 1999)

The heartbreaking final scene of Paul Thomas Anderson’s Magnolia is a quiet moment, but a superb way to end such a singular film. Officer Jim, played by John C. Reilly, goes to see Claudia (Melora Walters) as Aimee Mann’s “Save Me” plays, to tell her that he wants to make it work with her and to stress the purity of his love for her. Barely audible under the song, he does so, and we watch only the process of reactions that play out on her face. It’s a lovely way to end the film, especially with everyone still wrapping their heads around the whole raining-frogs thing. This broken woman turns and startlingly looks directly into the camera, breaking the fourth wall, and smiles. It’s so simple yet so powerful, suggesting there is reason to hope after all.

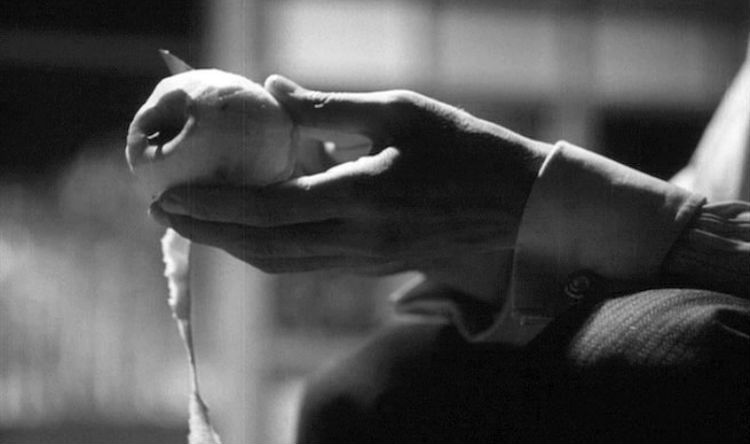

2.) Late Spring (Yasujirō Ozu, 1949)

This is perhaps the saddest ending I have ever seen. It’s a common ending for director Yasujirō Ozu, with the widowed Chishu Ryu sitting alone in his home after marrying off his daughter (fittingly, it’s how his last film, An Autumn Afternoon, ends). Noriko (Setsuko Hara, another Ozu regular) doesn’t want to leave her father, but she is under extreme pressure to be married off, and eventually stops resisting and consents to the marriage. This despite the fact that she admits she can’t see herself happier than she is now, taking care of him, but this is simply how things are done. “That’s the order of human life and history,” he says, with great sadness. After the wedding, he returns home alone, sits down and begins to peel an apple. Never has someone peeled an apple with more sadness. The peel falls to the floor and he looks down at the ground in grief. It speaks to their closeness, to this society’s outdated customs, to the tragedy of caring about social appearances. I’m tearing up just writing about it.

1.) Before Sunset (Richard Linklater, 2004)

Many of my favorite final shots seem to be cynical and depressing, so Before Sunset is even more notable for being triumphantly euphoric and sweetly hopeful. Whatever complications that next sequel may bring, in this moment the only choice we have is to believe in true love, and Jesse (Ethan Hawke) and Céline (Julie Delpy) have found it. Jesse has a plane to catch, and they’ve been dancing around the obvious fact that neither of them wants him to leave. “You are gonna miss that plane,” she tells him, and very simply he replies, “I know,” and we cut to her dancing to Nina Simone, and we fade out. Closing on this intimate moment, with her free and silly dancing, is emblematic of the series and their romance, so to end on that image is delightfully resonant. We can feel the yearning in this room, and can imagine where their lives will go from here, and to end in the middle of this moment is true to the idea of time moving, lives intersecting and dispersing, romance thriving despite it all. It’s positively life-affirming.

3 thoughts on “10 Memorable Closing Shots”

You have a piece on memorable closing shots without even a mention of Truffaut’s ” Les quatre cents coups”? Seriously? Seriously???

The way you described the ending to LATE SPRING again makes me get teary eyed. There’s plenty that could’ve been included, but I’m sure most people think of SUNSET BOULEVARD.

Pingback: 10 MEMORABLE CLOSING SHOTS IN FLICKS