Muhammad Ali is a figure of such reverence that the very mention of his name evokes mythic superlatives. Olympian. Champion. The greatest. His greatness was achieved with a physical and mental ferocity that was steadfast both inside and outside the ring. Though his legendary title bouts have been richly chronicled in TV and film, it’s curious how his battles in the public arena have not been given the same attention to detail. There are many of us today who cannot recall that this beloved hero was once one of the most reviled “negroes” in 1960s America.

It is these trying times that Bill Siegel’s The Trials of Muhammad Ali dives into, looking unblinkingly into the darkest days of Ali’s professional career. With newly-unearthed footage, it rediscovers him as a brother, a son, a Muslim in the early days of the Nation of Islam, a sweet-talking youngster, a thespian, a conscientious objector, and an exiled champion.

The film introduces Ali by presenting early glimpses of his family, including stories from his brother Rahman who also became a professional boxer. We witness his ascent from Olympic gold medalist to the professional ranks with the help of (overwhelmingly white) financial backers from his hometown of Louisville, Kentucky. Their lone surviving member reveals the roots of his original name, Cassius Clay.

The Trials of Muhammad Ali then turns its focus to its subject’s involvement in the Nation of Islam, a crucial element in the blossoming of his social consciousness during America’s burgeoning civil rights era. We hear how he was religiously and politically influenced, and learn why the Nation appealed to urban African-Americans more Martin Luther King’s movement of southern rural origins. We also see his relationships with the Nation’s two most important figures, Elijah Muhammad and Malcolm X, and the contrast of Ali’s attitudes towards the latter, pre and post-assassination, are astounding.

It’s remarkable that all this personal and social turmoil occurred as Ali rose to the top of his sport. While converting to a new religion under an organization reviled by many for its own kind of discrimination, he also became the most visible athlete in the world. The film elucidates how he resonated globally, particularly in regions without Judeo-Christian influences that were rarely visited by sporting champions. There’s a reason Zairians rooted for Ali even though George Foreman was darker skinned.

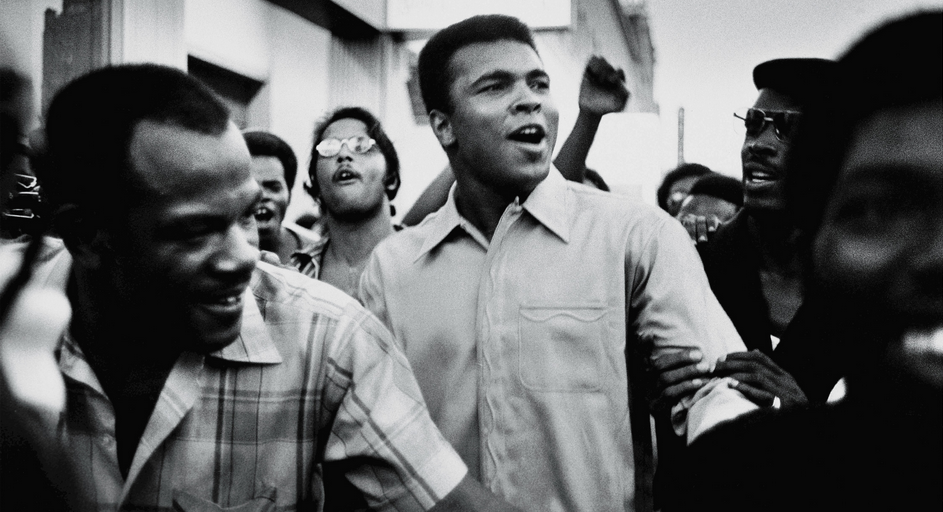

And of course, there was the war. Ali’s stand against Vietnam is well-documented in history books, but the furor that many felt about his decision has largely been forgotten. The film’s footage of the backlash against his stance, in both black and white circles, is jarring. His name, though it means “beloved of God,” became synonymous with “un-American.” His choice stripped him of his title and livelihood for several years, causing him to take to the lecture circuit, and even theatre, to make a living.

Hardly anything in the film is trumped up in a maudlin, suspenseful, or triumphant manner. It lays out its chronology and context through archival clips and interviews with those who were with Ali at key moments in his life, as well as noted personalities and journalists. We gain cultural insight from Salim Muwakkil, former editor of the Nation of Islam newspaper “Muhammad Speaks.” We smile at lighthearted stories from Ali’s second wife Khalilah Camacho-Ali. We get first-hand accounts of Ali’s conversion to Islam from “Captain Sam” (Abdul Rahman Muhammad), who led him to convert. We learn of his pugilistic prowess from Robert Lipsyte, the current ESPN ombudsman who covered Ali’s career. We even hear from Louis Farrakhan, the current leader of the Nation of Islam, on Ali’s effect on black America.

These recordings that director Bill Siegel has brought back to us are a gift, a monumental and careful effort to directly address Ali’s legacy not by fawning over his accomplishments but by showcasing the past without embellishment. Here is Ali unsanctified, still shocking but for different reasons. The film forces us to reckon with his words, deeds and imperfections. He’s human like the rest of us, but courageous beyond any of his contemporaries. What do today’s sporting titans, disgraced or otherwise, fight for?

The Trials of Muhammed Ali is unfortunately relevant because as much we’d like to deny it, watching Ali deal with his country’s anger at the color of his skin and his Muslim name is a sad reminder that nothing has really changed. His story is America’s story. As Robert Lipsyte puts it, “There are so many ways of looking at him that have only to do with us, and nothing to do with him.”