In a recent video essay for All That Jazz, Matt Zoller Seitz refers to director Bob Fosse’s editing style as evoking a “continuously unfolding present tense moment.” Influenced by the French New Wave and Sam Peckinpah’s ballets of violence, Fosse Time, Seitz argues, was an editing technique that cut openly between past and future, condensing and elongating moments across an “eternal now.” Ten years after All That Jazz, Bolivian director Jorge Sanjines would go even further than Fosse, expressing a form of looking at time that predated history itself. La Nación Clandestina—which tells the story of an indigenous Aymara, returning to his homeland after a period of exile and western acculturation—was Sanjines’s attempt to supplant linear, western logic and express the Andean concept of “naupaj mapuni,” of looking simultaneously into the past and the future. It’s a barely known and sorely underappreciated gem whose absence from cinematic canon serves as a stark reminder of the continuing need to expose more light to the films of the global south.

Film goers were most recently exposed to Bolivia as the barren site of a failed water coup in the incomprehensible ‘Quantum of Solace’ When Indiana Jones traveled to bordering Peru in search of the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull, film goers were presented 1950’s South American Indio as secluded, spear wielding savages. And while Peru may now lie separated from Bolivia by post-colonial borders, the two countries were once part of the Incan Empire, and both share the scars of history and persisting heritage so well demonstrated in La Nacion Clandistina. Both also remain predominantly nonwhite, made up of a majority Indio or mestizo population, with Guechua and Aymara among their official languages. So while Bolivia might be little more to modern screenwriters than a cipher for fantasy adventure stories, this film shows us a country and a people struggling through the complex transition from dictatorship to democracy, a rich political backdrop to the story of a young man embarking on the long journey home.

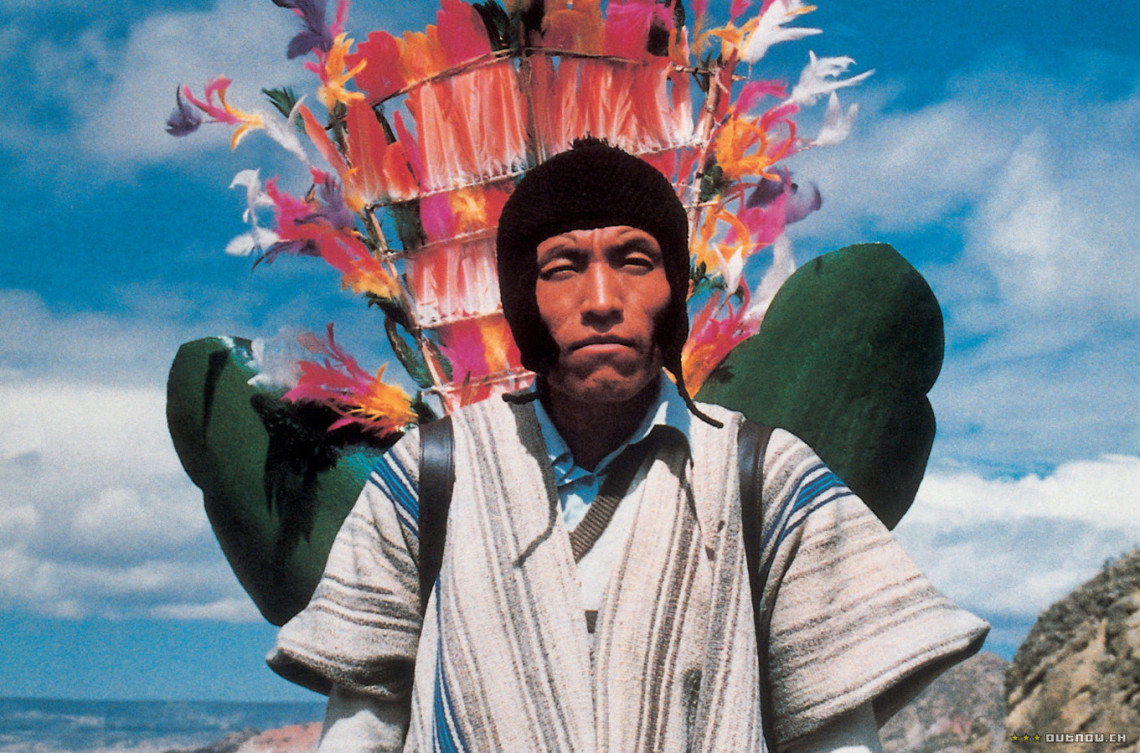

La Nación Clandestina is a road movie through space and time. The traveler, Sebastian, carries a ceremonial dance costume on his back across rural Bolivia, with the intention of performing a sacred dance on his native soil—returning home to dance until he dies. The journey is constructed out of 100 long takes, the camera moving through and within the action, traveling non-linearly through events in Sebastian’s life. Released at a time when many indigenous Bolivians were still banned from cinemas by persistent racist policy, the film was built to articulate a native perspective to wealthy, white audiences. Its techniques are antithetical to the typical, Russian montage style of shot construction, instead reflective more of Seitz’s “Fosse Time.” Sebastian frequently gazes into the distance, only for the cut to transport the viewer into the past or future—a literal manifestation of “naupaj mapuni.”

As Seitz notes, Bob Fosse’s experiments with non-linear editing in the 1970s were part of a growing break from traditional techniques. And though he is correct to say that contemporary audiences are much better trained to accept sudden temporal shifts across cuts, the most famous edits in film history still tend to be associative and linear. In 2001: A Space Odyssey, for instance, a bone flies into the air and becomes a space station; in Lawrence of Arabia, Lawrence raises the match to his face and blows it out, magically summoning the endless desert landscape. But when Sebastian in La Nación Clandestina pauses at the crest of a hill and the cut leads us into a moment from his past, or when a faraway shot of him fighting with his wife in the past pans to his face in the present, the meaning is not associative. This is not “and then” so much as “eternally meanwhile,” which may have been new to filmmakers in the mid-20th century, but has defined the thinking of Andean and other indigenous cultures for countless centuries. Film, it seems, is the art form that most naturally allows for the transcendence of typical Western storytelling.

Both All That Jazz and La Nación Clandestina are about men approaching their own death and looking back across the tides and islands of their lives. But the death awaiting Sebastian is far more tragic in nature than Joe Gideon’s. When he finally arrives back home, he finds the already isolated village of his youth even further stripped of life, most of the adults relocated to the nearby mines. “You cannot stay here,” an elder tells Sebastian as he pitifully presents the costume he has carried in a bag through endless miles of desert. “I’m back,” Sebastian replies, “because this is where I come from.” Then, he weeps—and there is something profoundly cosmic about the tears Julio Baltazar (this was his only screen performance) sheds, existing somewhere outside of time like Renée Maria Falconetti’s tears for Carl Dreyer in The Passion of Joan of Arc. These are not the tears of simply a man passing, but of an entire culture leaving the world, its purity never to return. The dance Sebastian brings home is one that has already begun to vanish from his culture’s memory, as indicated by the bemused fascination of the children who watch him don his ceremonial robes, struck by the non-familiarity of their own heritage. Sad as it may be, Joe Gideon’s fall, as a result of narcissism and substance abuse, is a distinctly modern one. Sebastian’s death stands for that of an entire culture for whom violence has supplanted music.

And finally, Sebastian dances, encumbered by an oversized mask and ceremonial dress, his movements awkward, the slight bend in his elbows almost feminine. Bells jingle on his legs. Tiny brush fires smolder around him, casting pale smoke across the arid landscape. These are the last steps he will ever take. The oversized decoration of his ornamental mask snaps in half, hanging pitifully like a broken ear. Even as his energy fades, the soundtrack’s drums rise in power, as Sebastian’s physical strength is transferred into spiritual redemption. It is an image as flush with personal need as Chaplin’s eyes looking up above a bunch of flowers in City Lights, as redemptive as any canned Hollywood happy ending.

Yet this image, like the ghost of some alternate universe’s more inclusive film canon, is unavailable on DVD. As of this writing, the film exists (thankfully with English subtitles) on Youtube, though in a fuzzy transfer taken from Brazilian television. But unlike what might have confronted James Bond or Indiana Jones, the ruins of La Nación Clandestina contain not buried magical artifacts, but active community councils, struggling to navigate the complexities of encroaching modernization. Sebastian is neither a stoic wise man nor a faceless ‘primitive’, but a brother and an artist. He is a son and a husband and an alcoholic. And, like Joe Gideon before him, he is a dancer of the perpetual now.

…

Authors’ Note: Facets Multi-Media is a distributor of rare and foreign films. If you would like to suggest they consider La Nacion Clandestina for release, tweet them so @facetschicago. Alternately, if you are aware of distributors specializing in South American or Indigenous films, let us know in the comments.