This article originally appeared at Gazing At Film.

Hong Kong is a nation without a past. After spending time as a British colony, it was then handed back over to China causing it to be in a constant state of motion. Unlike America, which began as colonies then fought and unified through the Revolutionary War thereby creating its own history, Hong Kong is without a unified history. “Hong Kong has no precolonial past to speak of” (Abbas pg. 2). Beneath Hong Kong’s exterior, you won’t find a Chinese identity, nor will you find a wholly British one. Instead Hong Kong finds itself utterly removed from the temporal narrative of both nations. It is constantly progressing forward towards nothingness, a place removed from time, striving for a collective history it will never achieve. Wong Kar-wai perfectly captures this sense of motion and time, and the inability to connect on a historical, and intimate level. In Chungking Express, the film that has essentially become the calling card for his distinct style, Wong expertly captures the hyperreality of Hong Kong.

Before being able to understand Chungking Express within the framework of Hong Kong, Hong Kong’s post-colonial status must first be understood. Colonialism is the step that allows imperialism to transition to globalism. “The rise of globalism spells the end of the old empires, but not before the offspring’s of these empires, the previous colonial cities, have been primed to perform well as global cities” (Abbas, pg. 3). Hong Kong, since being returned to China, is in this process of transition. However this process leads to a broken and fractured space in which disappearance, cultural and otherwise, occurs. “The presence of these strange historical loops implies a more complex kind of colonial space produced by the unclean breaks and unclear connections between imperialism and globalism, which is how colonialism in Hong King must now be considered” (Abbas, pg. 3). This very tangible sense of disappearance is a crucial aspect of Wong Kar-wai’s films, but it is especially apparent within Chungking Express. People seemingly blend into the vibrations of the city. Eyes lock for a mere moment, and flesh grazes flesh. These brief flashes of intimacy are all that can occur in such a fluctuating space.

Under British rule Hong Kong suffered from a crisis of identity. Once it was returned to China in the 1990s, any possibility of finality or permanence was stripped from Hong Kong’s historical narrative. “The sense of the temporary is very strong…the city is not so much a place as a space of transit” (Abbas, pg. 4). In a cultural sense Hong Kong has almost always been comprised of a number of transients, many people only remain for a short time, never permanent. On a purely physical level, Hong Kong has always been a major port, a place of constant travel. Hong Kong is continuously functioning at different temporal narratives. The fact that Chungking Express is composed of two narratives that happen simultaneously, one only connected to the other through brief punctures of the background space by characters from the other narrative, is entirely representative of Hong Kong’s simultaneous spaces and speeds. “Hong Kong will increasingly be at the intersections of different times or speeds” (Abbas, pg. 4). Hong Kong itself has become an ephemeral space.

While Hong Kong is now once again a part of China, in reality it’s only tangentially subordinate to Chinese rule. While under British rule Hong Kong made incredible advances, carving out its own cultural and political narrative. Now due to its current situation, politically subordinate yet advanced in almost every other aspect, Hong Kong is truly a place removed from both narrative and time. “This amounts to saying that colonialism will not merely be Hong Kong’s chronic condition, it will be accompanied by displaced chronologies or achronicites” (Abbas, pg. 6). This situation has never occurred in colonialism’s history, which is why the only proper term to use is postcoloniality. Like the cart that got ahead of the horse, Hong Kong is no longer a colony but it also isn’t decolonized. “In a special sense: a postcoloniality that precedes decolonization” (Abbas, pg. 6). As Hong Kong attempts to construct a new subjectivity for itself, it’s forced to grapple with these differing speeds and sense of disappearance that is inherent with postcolionalism. Through his cinema, Wong Kar-wai attempts to negotiate with, and transplant to the cinematic medium, this postcolonialist subjectivity.

During the arduous two year editing process on his wuxia film Ashes of Time, Wong decided to make a film quickly and cheaply. The film that was born out of Wong’s desire to keep his cinematic muscles from atrophying was Chungking Express. It is fitting that a film about the continuous motion of Hong Kong and the multiple speeds of its residents was created so quickly while Wong was engaged in a much longer process. Chungking Express in a sense is an excellent example of postcolonialism in the cinematic medium. Though there is a narrative (in fact, there are two) there is the pervading sense that there is no past, only the continuous flux of time in that the characters are caught within. “Held together by a series of happenstance encounters, the overall structure of Chungking Express reflects the rhythms of social interactivity in a dense urban environment, where stranger and stories rub up against each other and become momentarily entangled” (Ma, pg. 129). While cinema is understood as the light, and therefore a moment in time, being permanently captured to film, postcolonialism and Chungking Express is defined by its temporality and fleeting moments.

In order for its grasp, or lack of grasp, on time and history to be fully appreciated Chungking Express’s narrative must first be acknowledged. In the first narrative a police officer becomes briefly entangled in the life of a female drug trafficker. In the second narrative a woman working at a food stand inserts herself into the life of an unnamed cop who is suffering from a breakup. Besides some of the characters from the second narrative momentarily appearing during the first narrative, the only real overlap between the two is the Midnight Express food stand and Hong Kong, specifically the Chungking Mansions complex, itself. The overlapping narratives are representative of the multiple speeds and times that postcolonial Hong Kong inhabits.

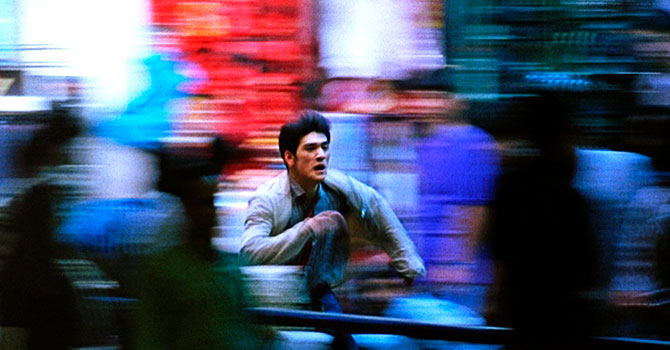

The Chungking Mansions complex is a massive, and cavernous area that is composed of apartments, shopping malls, stores and sensory overloading amounts of neon. The way Wong’s camera captures the plethora of colors, sounds and sheer movement of all the people elevates the Chungking Mansions, and therefore Hong Kong, to a level of pure spectacle. Wong constructs the frame through color and texture, like a painter blurring and smearing the canvas. “Chungking Express presents life as a radiant blur” (Hampton). Though all of Wong’s efforts to effectively blur and distort the senses are done in an effort to prevent Hong Kong, the true subject, from becoming lost. “Hong Kong cinema: it may have found a subject, Hong Kong itself, but Hong Kong as a subject is one that threatens to get easily lost again” (Abbas, pg. 25). Wong’s visual and sensory overload is a critique of the colonial space, a space which cannot support the weight of a fantastically exaggerated Hong Kong. Through the subversion of clichés visually and thematically, Chungking Express is a romance where the potential lovers experience almost no physical contact, Wong is creating a postcolonial film. “…of doing something else within the genre, of nudging it a little from its stable position and so provoking thought. This is postcoloniality not in the form of an argument; it takes the form of a new practice of image” (Abbas, pg. 36).

Chungking Express is a film about glances and fleeting seconds. It’s construction as a film relies on the moments that Hollywood films usually disregard. Hollywood cinema has a rich history that allows it to skip these seemingly temporary moments, but Hong Kong and it’s cinema has no history. Seemingly small narrative moments are brought into focus. A cop buys a can of pineapples everyday in order to mark the passage of time, and a food stand worker desires an unnamed police officer from a distance. The multiple temporal narratives are elliptical and lucid. The narrative of Chungking Express, but really the narrative of Hong Kong, is in constant motion, a state of flux.

Due to its postcolonial status, Hong Kong is in danger of disappearing. “In other words, the danger now is that Hong Kong will disappear as a subject, not by being ignored but by being represented in the good old ways” (Abbas, pg. 25). Due to its lack of a distinct history the fear is that the only way to keep up with a subject that is always on the precipice of disappearing, is to use preconceived binaries to define it. These binaries create a sense of déjà disparu: “the feeling that what is new and unique about the situation is always already gone, and we are left holding a handful of clichés, or a cluster of memories of what has never been” (Abbas, pg. 25).

Seemingly the only way to preserve Hong Kong’s subjectivity is through the clichés of déjà disparu, “its main task is to find means of outflanking, or simply keeping pace with a subjective always on the point of disappearing-in other words, its task is to construct images out of clichés” (Abbas, pg. 26). But Wong through the visual decadence and elliptical narrative of Chungking Express, and the majority of his oeuvre, rebels against this notion of déjà disparu. Wong shatters the clichés of the ‘old ways’. He is able to express Hong Kong’s postcolonial subjectivity through film because he made Chungking Express within the same ‘in-between’ space that Hong Kong itself occupies. No past or future, just constant motion.

Hong Kong is neither free nor is it a colony. Due to its traumatic movement from a British colony back to being a part of China, Hong Kong has no real past to speak of. It exists at multiple speeds and temporal narratives. It is situated in between a colony and something far more advanced. For the first time in the history of colonialism, Hong Kong has become postcolonialist. Through his cliché shattering style and ephemeral narrative constructions, Wong Kar-wai is able to translate Hong Kong’s subjectivity into the filmic medium. Chungking Express, like Hong Kong, is a film of the here and now. It operates outside of traditional narrative, and functions in a continuously fluctuating space. Narratives, colors and people all exist simultaneously, all blurred together at varying speeds. Both Chungking Express and Hong Kong are constantly teetering on the edge of disappearance, yet Chungking Express preserves Hong Kong through its motion in constant flux.

Works Cited

Abbas, Ackbar. Hong Kong: Culture and the Politics of Disappearence. Vol. 2. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, n.d. Print. Public Worlds.

Hampton, Howard. “Blur as genre.” The Free Library 01 March 1996. 08 May 2013 <http://www.thefreelibrary.com/Blur as genre.-a018403701>.

Ma, Jean. Melancholy Drift: Marking Time in Chinese Cinema. Hong Kong: Hong Kong UP, 2010. Print.