The names and faces of Marlon Brando and James Dean are instantly recognizable in contemporary popular culture, while Montgomery Clift remains a name and face relatively few today recognize. Oh, maybe they’ve heard of him, perhaps as the subject of a particularly catchy song by The Clash, but not many would call Clift “familiar.” And yet, at his peak, Clift was one of the biggest stars in the world, a pioneer of performance. He showed off the method before Brando. He was the rebel before Dean. He was the guy who made Burt Lancaster nervous acting opposite someone of such talent.

Before Clift, big screen performers could be loud and overly expressive, like hangovers of the early talkies, when actors struggled to make themselves heard and seen over the nascent technology. Subtlety, apparently, came not so easily to leading men of the era. But Clift, who got his big break in 1948 with the one-two of Red River and The Search, was different. Trained in theatre, he was an effortlessly naturalistic leading man. And unlike the typical heroes of the era—think macho obelisks like John Wayne, Robert Mitchum, and Kirk Douglas—Clift’s characters were rarely strong, and seldom in total emotional control. They could be defeated; they could feel too much.

Clift had the unique ability of playing complete bastards while still convincing you that he was the victim. One can’t help but feel sorry for Clift’s scheming gold-digger at the end of The Heiress (1949), and the same for his petulant misogynist Terminal Station (1953). The suggestion of vulnerability in his every movement allowed his characters to get away with almost anything. But it was in A Place in the Sun (1951), a twisted romance in which he played a lost young man torn between two women, where Clift first revealed the true extent of his fragility, a perfect match of actor and character. A Place in the Sun centres on a man utterly tortured over the chore of existence, and Clift, isolated as a child and uncomfortable with his celebrity status as an adult, bore the screen persona of someone terminally lonesome.

In Scandals of Classic Hollywood, author Anne Helen Petersen points to one particular quote from Clift—“the closer we come to the negative, to death, the more we blossom”—as evidence that he purposely nurtured the pain he had in him for his art. It resulted in some enormously powerful displays, the likes of which had no forebears. For instance, in From Here to Eternity (1953), in which he played a soldier refusing to cooperate with his superiors, Clift predated the James Dean-type rebel. Indecently attractive and tough on authority figures, Clift’s character Robert E Lee Prewitt is like the monochrome template for Rebel Without a Cause’s full-color Jim Stark.

From Here to Eternity would bring Clift an Oscar nomination for Best Actor—his third—but to get there he pushed himself like no other actor of his day. Arguably the first notable case in the history of method acting for the screen, Clift learned the cowboy life in preparation for Red River, spent a night locked in the San Quentin Pen death house the night before his execution scene in A Place in the Sun, and—in the most extreme example—learned to box, bugle and drill military-style for From Here to Eternity. Such was Clift’s immersion that an audience member asked The Search director Fred Zinnemann how he’d gotten a soldier to act so well.

Marlon Brando’s cinematic debut came in 1950, two years after Clift had already become a sensation and acted as method acting’s flagship for the screen, and yet it’s Brando who is often cited as the quintessential early method performer. It’s understandable on some level: though Clift possessed a quieter power, it’s easy to argue that Brando was the better actor, given the diversity he displayed over his career. But then, he had longer to prove himself. By the time Brando made The Godfather, Clift had already been dead six years.

The golden period for Clift ended before he’d finished making his ninth film. In 1956, whilst midway through shooting the period romance Raintree County with Elizabeth Taylor, he was victim to a car crash that left him disfigured and forevermore addicted to a cocktail of pills and alcohol. Many of Clift’s films post-crash would see the new, basically unrecognizable actor delivering lines in what appears to be a medicated haze (his preferred drink after the accident was apparently orange juice, vodka, and crushed Demerol). His star would fade quickly. After Clift got out of hospital and finished the picture, many cinema-goers flocked to watch the derided Raintree County with one morbid purpose: to see if they could spot the difference between the handsome actor of old and the plasticky, dazzled new model.

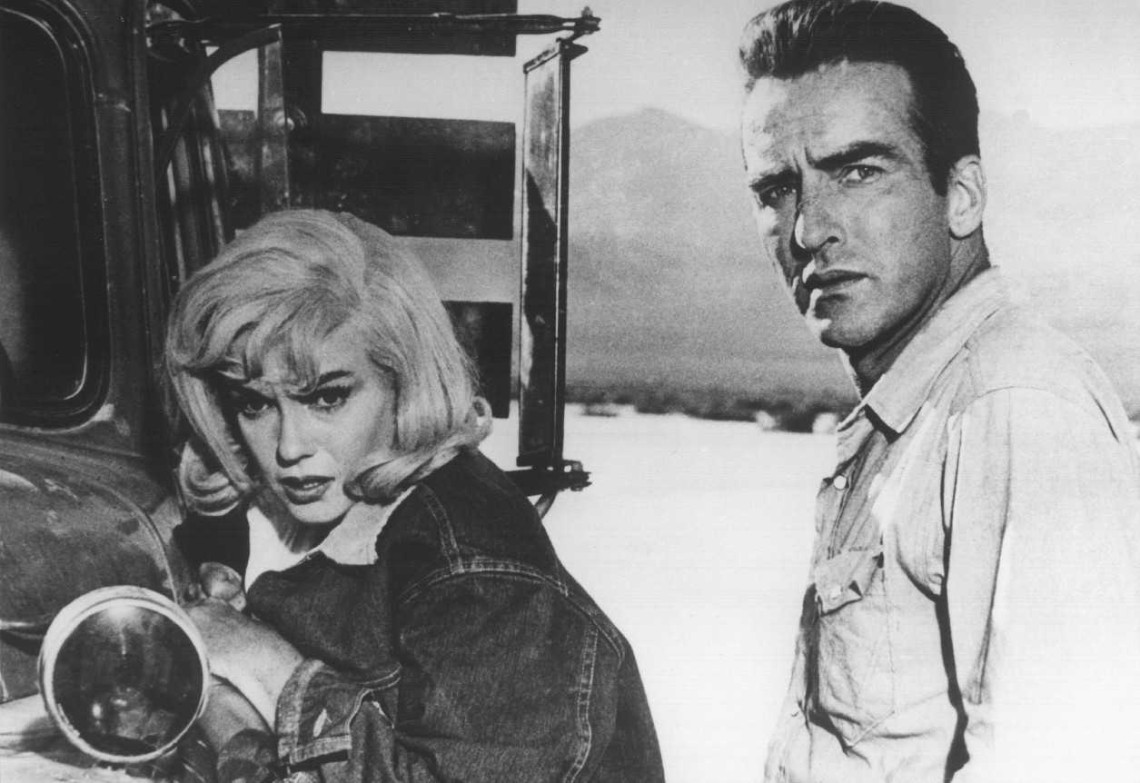

Subsequent films are hit and miss, with Clift’s performances varying in quality. He’s solid in a pair of John Huston collaborations, Freud: A Secret Passion (1962) and The Misfits (1961), compellingly cerebral in the former and wired, dumb, and tragic in the latter. His turns in the 1958 pairing of The Young Lions and Lonelyhearts, on the other hand, leave much to be desired. His 15 minutes in Judgement at Nuremberg (1961), meanwhile, are particularly sour, not because Clift’s turn in it is bad, but because of the film’s production context and how Stanley Kramer managed to tease out the performance.

Playing the part of the mentally and emotionally broken Rudolph Peterson, Clift drank so heavily during the Nuremberg shoot that he struggled to remember his words. Kramer told Clift to “forget the damn lines” and improvise, thinking it would add to the confusion of the character. It works—as Peterson throws a perplexed look at the court judge or timidly asks the prosecution to repeat a question, it’s impossible to know whether that’s the character talking or just the drunk, drug-addled actor.

Clift’s depleting reputation as one of the great and influential movie performers is down to a combination of factors. For one, his films that were so popular in his time are less so today. Classics A Place in the Sun and From Here to Eternity are to some extent Hays Code-products of their time, less in vogue now despite their intact artistic and socio-cultural merit, while Clift’s breakthrough project, The Search, is the kind of prestige weepie that might today be dismissed as “Oscar bait.” (The fact that Clift never won an Oscar for The Search or for the three other films he was nominated for hasn’t helped in this regard, either.)

Then there are the great films of Clift’s that simply don’t get the recognition they deserve. Terminal Station, written by Truman Capote, directed by Vittorio de Sica, and butchered by David O Selznick on release, deserves to be reappraised in its restored form. Other films have just fallen into obscurity, for one reason or another: Alfred Hitchcock’s whodunit I Confess, as thrilling as any of the director’s 1950s output; docudrama The Big Lift, which casts mostly non-performers against the backdrop of a bombed-out Berlin; and Elia Kazan’s gorgeously composed, sumptuously performed Wild River.

What’s more, Clift, unlike Brando, had a dearth of truly iconic roles. He was the more understated performer, choosing often to keep characters introspective and introverted, where Brando would offer livelier interpretations. Clift always opted for the less showy path. See, for instance, the scene in From Here to Eternity in which a tearful Prewitt sounds reveille the morning after his friend has died. Lesser actors would probably try to over-sell it, but Clift holds deadly still. The eyes water, but there are no grand emotional gestures, no lines yelled in an attempt to achieve greater impact. It’s the stillness that devastates, as Clift knew.

Perhaps most impactful on Clift’s reputation, though, is that he went out slowly, with a proverbial whimper. Unlike James Dean, who burned out in a car crash at the beginning of his career, or Marilyn Monroe, who succumbed to a drug overdose at the height of hers, Clift was victim to what his Actors Studio teacher Robert Lewis called “the longest suicide in Hollywood history.” Dean and Monroe went out young, beautiful and—on-screen at least—bursting with vitality. Clift simply ebbed away over one long decade, his health steadily worsening, his looks severely fading (Clift’s last movie, The Defector, sees the actor looking a good decade older than his 45 years), and his former acting talent giving way to erratic, unsteady performances.

Then Clift died, in 1966, unremarkably middle-aged, years after he was ever considered a major star. That unexceptional idea of the man at his death seems to be the one that’s stuck. Had Clift instead died in that car accident in his prime, it would have likely kept up his celebrity image for longer. Audiences want to imagine their movie stars as examples of perfection, as immortals. It plays a big part in why the likes of Dean, Monroe, River Phoenix et al remain icons: They never lived long enough to become mediocre. Our idea of Clift can’t be so straightforward. But those performances of his, especially those captured before the downfall, should be for the ages.