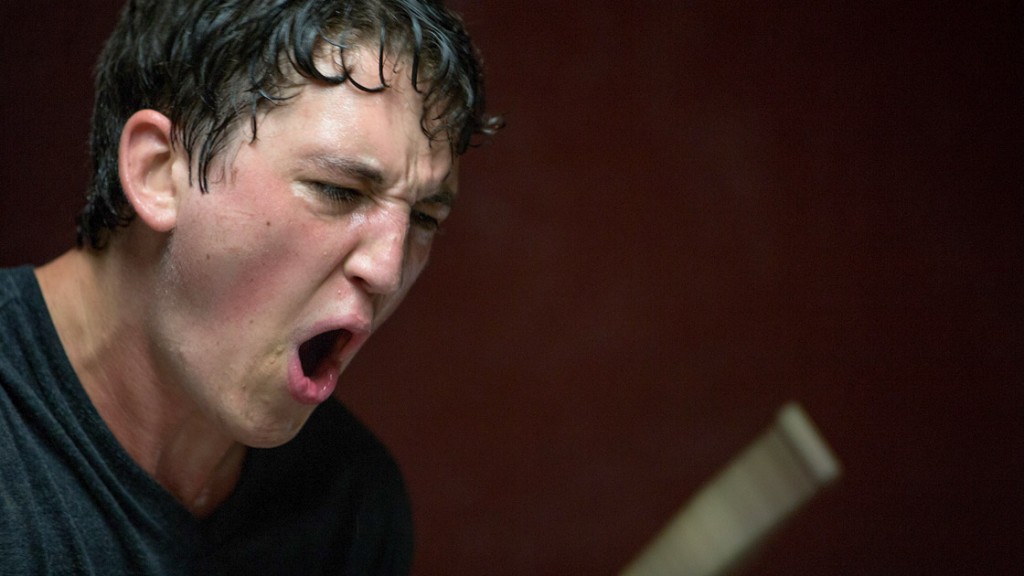

Only 29, Damien Chazelle has already written and directed two feature-length films, the little-seen (no longer, one hopes) Guy and Madeline on a Park Bench (2009), and now Whiplash, a Sundance Film Festival Audience Award winner this past January. Emotionally resonant, visually engaging, and dramatically satisfying, the film centers on the fraught, conflict-ridden relationship between an obsessive first-year jazz-drumming student, Andrew Neyman (Miles Teller); and the teacher-mentor, Terence Fletcher (J.K. Simmons). With his unrestrained, multidimensional performance as Andrew, Teller solidifies his well-earned status as one of the best actors of his generation. As for Simmons, this long-time character actor—best known for standout roles on television’s Law & Order and Oz, as well as scene-stealing turns in Juno and Sam Raimi’s original Spider-Man trilogy—is no less revelatory as the monstrous mentor who pushes Andrew to either artistic greatness, a mental breakdown, or both.

We sat down recently with Chazelle to discuss Teller, Simmons, the genesis of Whiplash, storyboarding, selling your soul for artistic greatness, dueling father figures, “soft” music and “soft” musicals, and his cinematic inspirations, among many other topics.

Movie Mezzanine: How did Miles Teller get involved? I first saw him in Rabbit Hole and like anyone who actually saw Rabbit Hole, I was really impressed by his performance.

That’s where I first saw him. I thought, “My god, I have to work with this guy.”

He was great in the Footloose remake too.

It’s funny. He’s done a whole range of films. I mean, he hasn’t been acting for that long, but he’s done such a range of stuff. He keeps getting typecast. After Rabbit Hole, he had a really hard time getting lighter, comic roles. He tried to do something against the grain, do a comic thing. Then suddenly, no one thought he could do dramatic roles. “Well, you’re the goofy sidekick.”

And he’s also a drummer.

There was literally no one who was better equipped for this role than Miles.

It was remarkable when I realized you weren’t cutting away, that was really Miles playing the drums, playing really sophisticated, difficult rhythms.

It really was. It’s really hard stuff that I had to learn myself to do when I was drumming. He’d been playing rock drums since he was a teenager, but he never had any real formal training. This whole world was totally new to him. We had to give a crash course in actual raw technique. He’s a sponge. He picks stuff up so quickly.

You have a drumming background yourself, correct?

Yeah, that was fodder for the script, stuff I’d been through, a conductor I had in high school. He was the inspiration. He certainly didn’t do everything Fletcher does in the film. Thank God. The stopping, starting…I just remember “tempo” being driven into me, an albatross I couldn’t quite master. As a drummer not mastering tempo, it’s like a painter being blind. I was constantly grappling with that and I just remember fear, stress, anxiety, dissatisfaction, and anger… all those emotions when I was playing music. I wanted to make sure the movie really talked about that.

Fletcher doesn’t have a filter of any kind. When he goes after a particular student, he doesn’t censor himself in any noticeable way. He finds their soft spots and goes after them hard. I was thinking of a moment early on when Fletcher asks Andrew about his family and you know almost immediately it’s not going to end well.

Fletcher is such an asshole. It was important with that character because you end the movie on an artistic high, you have to make the behavior that leads up to that as low as possible. At the end of the day, the movie has to ask a question. It’s what I wanted the movie to do. Do the ends justify the means? If the ends are great, you have to make sure the means are terrible enough that you’re not sure where you fall.

Fletcher was always conceived of as a larger-than-life monstrosity of a person. Once you give yourself that kind of free rein, then you just go all out. It’s weird trying to think of the worst possible things you can say. I think he’s a character who operates on shock value. He’s a character who pummels his students into submission. A lot of that is through the words that he says. He’s not a subtle guy. He’s a guy who comes in like a bulldozer and is ready to crush everyone in his wake if it means finding one great musician. He doesn’t care about the casualties that will litter the road. He doesn’t care about road kill. This one grain, the diamond in the rough is what he’s after. It was a bracing role to write. For J.K. Simmons, it was bracing…for him to sink his teeth into. It was important to never soften him.

All the terrible stuff he does, all the few good things he does all come from the same passion for music. He’s just a guy who lives and breathes jazz. He loves this music more than he loves any human being. It makes sense that he plays his music [late in the film], it’s with a real amount of love, but when he tries to teach people music, he’s going to be as exacting as possible.

I found the contrast between Andrew’s father (Paul Reiser) and Fletcher fascinating. They’re essentially dueling fathers/father figures, the failed writer-turned-teacher versus the music teacher. I couldn’t help but wonder if there were any similarities. Was, for example, Fletcher a failed musician who, seeing his own limitations, turned to teaching? Did his personal disappointments play a role in his teaching methods? Both Platoon and Wall Street came to mind too.

Wall Street benefited from having a seductive villain. There’s something to be said for that. There had to be some kind of Faustian bargain, of Mephistopheles seducing Faust, selling his soul for artistic greatness. That’s a fun story to tell.

To shift gears, I found the romantic relationship between Andrew and Nicole (Melissa Benoist) real and grounded. What attracts them initially to each other (i.e., their different outlooks and ambitions) eventually pulls them apart. Once their worldviews were established, the conflicts in their relationship seemed assured.

That was less drawn from life than generally trying to juggle life with art. I remember talking to Jason Reitman who was one of the producers on Whiplash and it was his suggestion to get at that a little more, to make it harsher, to make a real scene out of it. It was one of my favorite scenes to shoot and to cut mainly because the two actors, Miles and Melissa, bring so much to it. [Their last scene chronologically in the film] was actually the first scene they shot together. They’d never met before then. It was scheduling. They met that day and then they broke up.

It was an important moment to me because it was the one moment when you see Andrew’s actions have consequences beyond just himself. It’s one thing for us to feel pain for him, that he’s putting himself through pain, but this is a moment when he deliberately, callously makes someone else feel pain. But like Fletcher, he has a deluded sense of righteousness. He thinks he’s doing the right thing. If you asked Andrew, he’d say, “I’m doing the right thing for her. I’m getting her out before I hurt her.” He’s not thinking that what he’s doing right now is hurting her. He’s so deluded and in his own bubble. I wanted to capture how art or music can—if you’re not careful—make you an incredibly selfish person. It’s ironic because art should be all about compassion, about human beings connecting with one another. There should be something really human about art, but it can make you this cold son of a bitch.

Was there a point where you felt that scene or any other scene was too harsh, that you were making Andrew too unlikeable as a character?

That was always the fight I was having. People wanted me to cut out the dinner-table scene. They thought it made Andrew too unlikeable, especially the way he goes after his family. There were similar scenes people were telling me to soften. I feel that we’ve seen the softer music movies. I didn’t need to make another “soft” music movie. I needed to make one that rubbed your face in how sadistic and fucked up this world could be. I would rather overdo that than err on the side of softening the edges.

On the flip side, that scene shows how little people are trying to connect or understand Andrew and where he’s coming from.

Me, personally, I root for him in that scene. He’s putting in a lot more work into his stuff than the Division III quarterback [one of Andrew’s near-age relatives] in the scene. It’s funny how people fall. I wrote that scene thinking Andrew was being a total hero, but that people reading it would think, “What an asshole! I’m so done with this character.” And then there’d be other stuff where I think Andrew is being an utter monster. For me, it’s interesting that at the end of the movie, a lot of people tend to react with a “Go get ’em, Andrew!” attitude. In my mind, the ending is a little more tragic than that, someone who’s given himself over to the dark side. You hope that you can engender different discourses, different interpretations.

He does turn away from his father near the end.

That was one thing we toned down in the editing. There was more to the scene between Andrew and his dad. It used to be really cruel. There are moments when you realize you have great actors like Paul Reiser and Miles Teller and all you need is a look, both crueler and more fully rounded than many pages of dialogue. It’s rare that fathers and sons sit down and talk about their feelings openly. As a single child and single father, they have a lot of history together when the movie begins and we’re watching that relationship slowly sever. It’s accelerated by Fletcher. It’s accelerated by the other dad.

Visually, Whiplash is not a static film by any means. I read that you filmed it in 19 days…

Yeah, $3 million and 19 days plus a couple days for inserts.

Did you storyboard?

Everything was storyboarded. I did animatics for the music sequences. Everything was completely pre-mapped out. I have a hard time figuring that shit out on the fly. That’s a whole other skill set. Some directors can walk on a set the day of and…[snaps fingers twice]. I’m not there yet. I had to sit by myself for many, many days and weeks and draw the entire movie. That’s as important a process as writing the script and casting the movie. It’s really a crucial part to bringing it to life. I just drew it all out like a cartoon. The DP [Sharone Meir] and I pored over that and that become our bible. We culled a shot list from that, ordering the storyboards. The storyboards were in edit order, so we culled a shot list from that. The AD created a schedule based on the shot list. Then we went on set and started banging stuff out. It was very methodical.

How much time did you have to rehearse?

We didn’t have time to rehearse at all. We did a table read, but Melissa was unable to attend. That was our only rehearsal. I got to work with Miles on the drums. Miles and I did about three weeks of drumming together, but in terms of actual rehearsal without the actors? Pretty much nothing.

Sometimes it helps. When you have something this intense, you don’t want to use people up with over-rehearsing. You wind up with something that’s a little too studied. Some directors love rehearsing. Some directors hate it. Some actors love it. Some hate it. I can’t really decide what I like or don’t like. In this case, it was just a matter of pure logistics. I tried to talk to the actors as much as I could. Get coffee with them. Exchange e-mails with them. I’d send Miles jazz charts. I’d send Miles what I thought Andrew’s playlist would be. I did the same with J.K. Simmons…what his playlist would be. I’d meet up with Melissa to talk about her character. I tried to have a lot of one-on-one time with people. At the end of the day, we didn’t have much prep time. Then you’re on set and you just have to execute. Hopefully you have good actors and good actors cut you a lot of slack.

By the way, did Miles actually bleed?

Miles bled by the end. Miles did so much drumming on set that it was bound to happen at some point. I think it happened during the fourth week, the blood started being real.

I just loved working with all those actors. The kids who played the bandmates … most of those guys weren’t actors. Most of them were just musicians or music students. They hadn’t been on film before.

To wrap up, what were your major influences or inspirations for Whiplash?

A lot of ’70s stuff. Gordon Willis. The Godfather. All the President’s Men. Visions of New York City in the ’70s. Taxi Driver. The Warriors.

The Warriors?

Yeah, scary ’70s movies. Lots of [William] Friedkin and [Sidney] Lumet and [Martin] Scorsese. That kind of darker vision of America we saw in movies in the ’70s that felt grounded but also nightmarish and fantastical. [Brian] De Palma.

I really felt that nightmarish quality late in the film when everything goes wrong for Andrew when he tries to get to the penultimate performance.

To me, I find it perversely funny, because it doesn’t actually matter. No one talks about it, no one refers to it ever again. He just gets up and keeps going. In any other movie, it’d be a major event. Here, it’s just something else to overcome, just a couple of blocks.