At first glance, the image is ironically funny. There’s a gun toting OJ Simpson, decked out in the robes of the Ku Klux Klan, taking aim at an anonymous redneck. Given OJ’s eventual fame, it’s impossible to separate the image from its context. It’s also the kind of image that could not be presented unironically today. Its very existence is like a twelve foot tall bronze sculpture titled, “Well, it was the 70s.” And while OJ’s hate group drag was just one of many instances of using those iconic white robes for everything from satire to exploitation to comedy, the image also fits into the evolving meta narrative of America’s relationship with the its own deep seated kyriarchy.

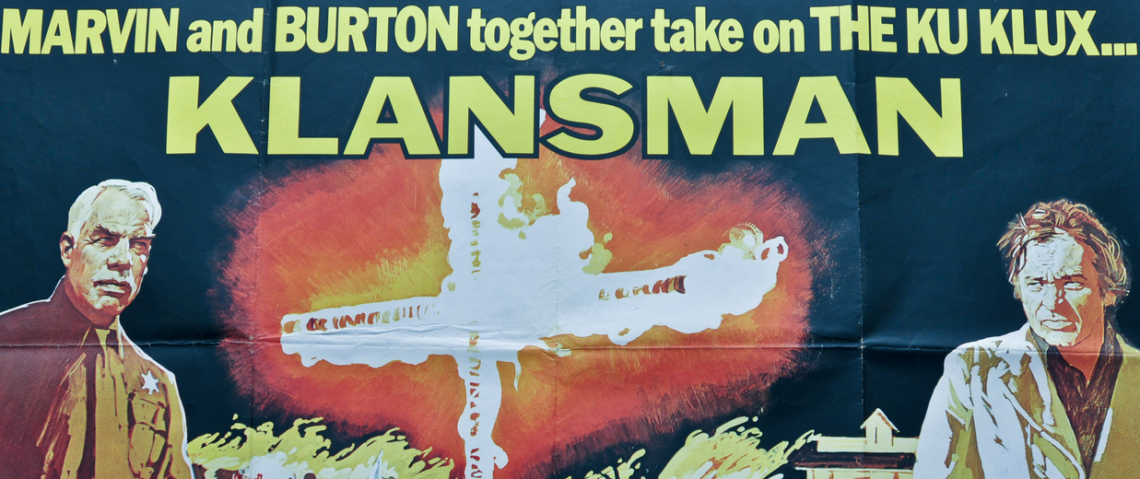

The film is 1974’s The Klansman, about the escalating race tensions in a rural Alabama town. It pinballs from the rape of a white woman by a never identified black man to the arrival of “communist agitators” to the rape of a black woman by a white cop, culminating in a firelight with the KKK. OJ Simpson runs around murdering good old boys to avenge a lynching. Lee Marvin is a cop. He was reportedly drunk during most of the filming. Richard Burton is a land owner sympathetic to the black population. He is visibly drunk for most of his scenes. Drunk stars and racial violence. This was a typical big budget, mainstream picture from the director of James Bond films. It was the 70s. But it was also everything else.

In 1963, Sam Fuller’s Shock Corridor used the image of a black man in a Klan hood as a satire of the insanity of racism. Fuller actually wrote the original treatment for The Klansman, based on the novel by William Bradford Huie. But his racial attitudes were always progressive, from his sincere depictions of Asian characters in China Gate and House of Bamboo to his career capping milestone White Dog. So it’s unsurprising that he was eventually removed. His interest in revealing the United States’ deep seated racism was unwelcome in 1974. His take would have come too close to a confrontation.

As it is, The Klansman is a perfect example of the literal definition of Blaxploitation. The naked bodies of black women are on full display, always about to be raped (the rape of the white woman occurs off camera). White on black violence is enacted, but only in retaliation against actual violence by a black person. OJ Simpson kills white people and says things like, “The only thing the man understands (is violence).” Lee Marvin is shocked that a black woman isn’t a virgin. “Everybody in the county knows a black girl gets popped by the time she’s thirteen,” he says, and the film doesn’t seem to question him. The “good whites” slaughter the KKK and the town hanging tree goes up in flames. It’s nice to think that Blaxploitation was a positive force, the empowerment of black film makers and actors. And in its initial creation, or in isolated examples, this was true. But more often it was like this, a white driven production reinforcing black stereotypes while oversimplifying the extent of contemporary racism.

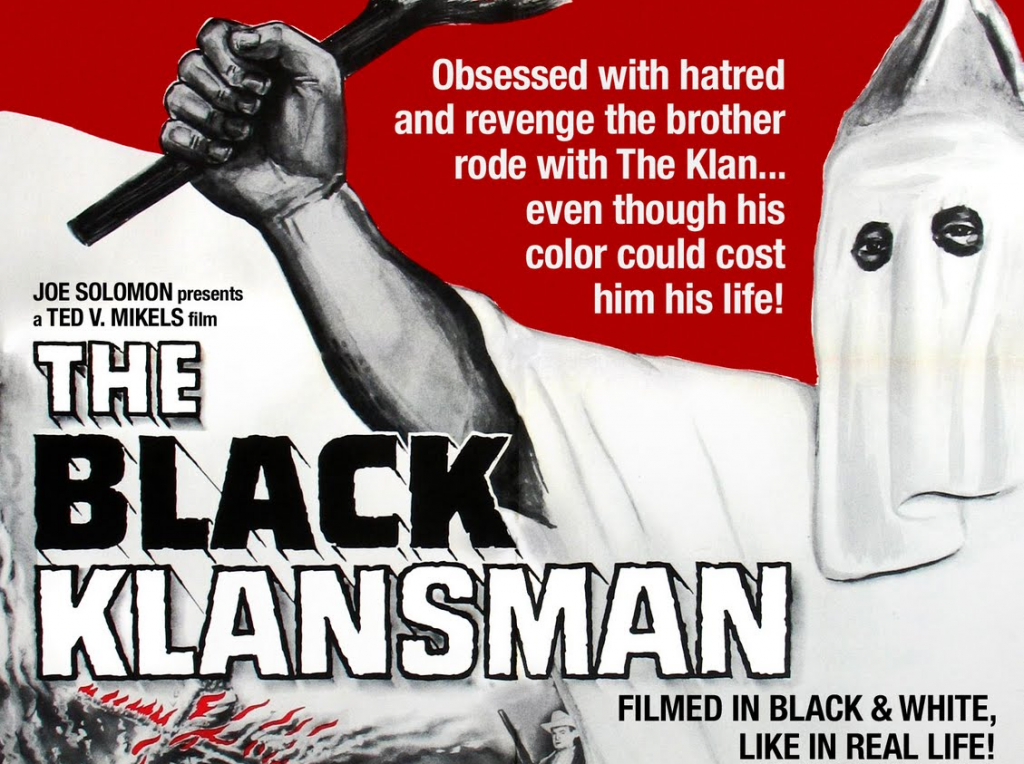

In 1966, Ted V. Mikel had directed and produced The Black Klansman (or I Crossed the Color Line’). Color Line has been retroactively labeled as Blaxploitation through its proximity in time to the 1970s, but in its tone and production design it more closely resembles low budget noir. The story is pulpy, the violence realistic. It plays out in the wake of the 1963 Civil Rights decision, with the bombing murder of a young girl outside a southern Baptist Church inspiring immediate memories of the six young girls murdered in Birmingham that same year. The hero is a light skinned northerner with a white lover. The murdered girl was his daughter. Donning a wig of relaxed hair, he infiltrates the local KKK.

Much like The Klansman, the film features the growing tension caused by outside agitators, through a group of hired city thugs. The hero, meanwhile, is privy to everything from a cross burning to an initiation ceremony, filmed in faux documentary style without music and with minimal cutting. Violence comes when the hero’s former lover is tied up with another black man and photographed, the supposedly sexual act used at the inciting incident for a double lynching.

In Mikel’s film, the Klan is a secretive cabal, operating in full costume and holding clandestine rituals in dark rooms. The first time we see them in The Klansman, however, is in suits and ties, sitting in a meeting hall. The mayor is called the “exalted Cyclops”, the deputy sheriff and other important men flanking him as he issues orders to, “not dynamite no churches”. When OJ arrives in disguise later in the film, a man catches sight of his ceremonial robes and says with surprise, “We haven’t worn our glory suits for a long time.” The contemporary Klan still wears robes and burns crosses, but even in 1974 they knew the value of good PR. These two films mark both sides of an unofficial demarcation line that separates one era of the Klan from another, a gradual shift in tactics and public image that came after their continually violent acts were met with increasing prosecution.

And maybe, on some collective level, people stopped being as afraid of them. The actor portraying the mayor in The Klansman appeared that same year in Blazing Saddles, illustrating the wide tonal span that could be applied to racial issues on film in 1974. The gag placing Cleavon Little in robes is part of a general tone that undermines the supposed authority of the KKK throughout the film. The refusal to cower in fear of the group is a far more effective deflation of their power than the overly obvious, mean-spirited melodrama of Black Klansman. Much like Dave Chappelle’s ‘Blind Racist’ thirty years later, filtering the power of a hate group through parody and slapstick deflates their supposed power. But filtered power is still power, and the so called “Contemporary Klan” perpetuated lynchings and racial murders into the 1980s. And when former senior Klansman Frazier Glen Cross murdered three Jewish people outside a synagogue in Kansas City this year, the disavowal of his actions by Klan spokesmen did little to contribute to any supposedly cleaned up image.

This month, the Daily Beast reported on how Detective Ron Stallworth, a black man, “infiltrated” the KKK in the late 1970s. According to Stallworth, he masqueraded as a prospective member of the Klan through a series of telephone conversations with then KKK leader David Duke. Stallworth has recently published a book on the experience, and his current involvement with the media seems to lend the story an unfortunate tang of self-promotion. Historic precedent for a more extensive act of racial subterfuge exists in the story of Walter Francis White. Born in Atlanta in 1893, he was exposed firsthand to the racial violence of the time, with his family surviving the Atlanta riots of 1906. Much like the protagonist of I Crossed the Color Line, White’s fair complexion allowed him to “pass” as a white man. Eventually working with the NAACP, he ventured into communities to investigate lynchings or race riots. He would operate under cover, claiming to be a hair tonic salesman or a white reporter from Chicago, using the openness of unsuspecting whites to gain information otherwise unavailable to black reporters. White began operating in early 1918, making his dangerous mission primed to coincide with the most violent year of race violence in US history, and putting him on the ground for one of its bloodiest events.

During the “Red Summer” of 1919, there were race riots in twenty five cities, including Chicago and Washington DC, while spectacle lynchings drew crowds by the thousands to the ritualistic murders of black men. It was an outcry of white power against the perceived insecurity of white dominance, a fear married to the need for the cheap resources of black labor. This was the same fear that would persist into the 1970’s and beyond, voiced by the racist sheriff in The Klansman as an economy dependent on racial exploitation.

Much as in The Klansman, the Red Summer saw rumors of Communists among the black sharecroppers of Helena, Arkansas. Whites converged on a meeting in a black church. The men were trying unionize. An exchange of gunfire left a white police officer dead. When the black community went into hiding, Governor Charles Gough called in the National Guard. Nearly a century later, it is impossible to determine the death toll. But in the ensuing hunt for supposed union “ring leaders”, guardsmen and lynch mobs hunted down and murdered blacks by the hundreds. They went from cabin to cabin, executing men women and children. Afterward, White was there to survey the damage. He would have heard the stories of mass graves and “dead niggers as far as the eye can see”. People must have told him about how entertaining it was, capturing the supposed organizer and setting him on fire with kerosene, about how he had burst loose of his bonds and had to be taken down by gunfire. About how it had taken a fire hose to quench his body. Maybe White would have still been able to smell the stench from bodies burned in pits. The killing fields had stretched for fifty miles and across two counties.

The events were labeled as fearful whites standing up to the threat of insurrection. One early report claimed as few as 14 dead, and all justified. It was part of the country’s meta-narrative, the idea that honorable whites were dealing as best they could with childish savages who could not handle the responsibilities of their own freedom. It was the same narrative that had allowed The Birth of a Nation’s heroic depiction of the Klan to rejuvenate the group’s then flagging membership. Both the Klan and film making are wedded with myth, utilizing imagery to distort memory and manipulate emotion. By the 1970’s, widespread violence targeted at black communities was still a recent memory. But the national meta-narrative had changed to encapsulate black voices, utilizing white fears of black violence to perpetuate the tawdry caricatures of the likes of The Klansman. Regardless of black voices like Mikel’s it was still the predominantly white power structure that was determining what images reached mass audiences. And Blaxploitation’s widespread portrayal of African Americans as pimps and criminals played into this same narrative, influencing popular opinions of urban groups in ways that would make more palatable future assaults on urban black communities.

As proven by I Crossed the Color Line, not every film of the era was based in caricature or exploitation. The period was replete with works by both white and black film makers, portraying both contemporary and historic African American life. Likewise, Mikel’ depicts an African American man’s struggle with his own skin color, a complex dynamic explored to an even deeper level in 1959’s ‘Imitation of Life’. But the disparity of the African American experience, and the films made about it in the 1970s, raises a question. Is it preferable to have an era replete with false representations of racial politics that is simultaneously more open to discussions and depictions of those issues? Or are we better off now?

Our landscape seems capable of producing nuanced, popular work that addresses race in America, like Fruitvale Station or Pariah. But the excesses of the 1970s have given way to a flinching reluctance toward topically driven films, their existence relegated to art houses or the bloated importance of Oscar season. Is the misguided exploitation of Black Klansman any more nuanced than Will Smith emerging from a Klan shroud in Bad Boys II? Would it be unfair to look at the ugly, homophobic White Chicks and condemn it for somehow failing to be about anything at all, even when given a premise potentially rich in satire? Are Tyler Perry’s cartoonish white villains and conservative morals preferable to the objectification of black bodies in the 1970s? Or are such films symptomatic of the neutering of our tolerance for racially motivated narratives, reducing all conversation to the broad simplification? To whom does the cinematic contribution to our national meta narrative belong, and who is it created by?

Films like The Klansman sanction selective truths, contributing to and drawing from our national meta narrative about the African American experience. But who else creates this narrative, and who is responsible for it? When considering the past at least, it behooves us to move beyond rote categorization. At least so far as the largely white community of critics and taste makers go, it is important to recognize our collective power, and to work to better understand the wide range of artistic, social and historic factors that has since been labeled ‘Blaxploitation’.

Sources and Additional Reading:

At the Hands of Persons Unknown, Rober Dray, Random House LLC, 2002

On the Laps of Gods, Rober Whitaker, Random House LLC, Jun 10, 2008

Rage in the Gate City, Rebecca Burns, University of Georgia Press, Aug 15, 2011

Next week: The LA Rebellion and the black film makers of UCLA.