“He hated his family because he knew that they were suffering and that he was powerless to help them. He knew that the moment he allowed himself to feel to its fullness how they lived, the shame and misery of their lives, he would be swept out of himself with fear and despair. So he held toward them an attitude of iron reserve; he lived with them, but behind a wall, a curtain. And toward himself he was even more exacting. He knew that the moment he allowed what his life meant to enter fully into his consciousness, he would either kill himself or someone else. So he denied himself and acted tough.”

These words come from Richard Wright’s Native Son, just before protagonist Bigger Thomas, young and black and living in Chicago in 1940, accidentally kills a white heiress. It’s impossible for Bigger to confront the sheer scope of his oppression, and the resulting poverty of his daily life. So he presents a false exterior, a curtain of bravado and petty theft behind which lurks disenfranchisement and helplessness.

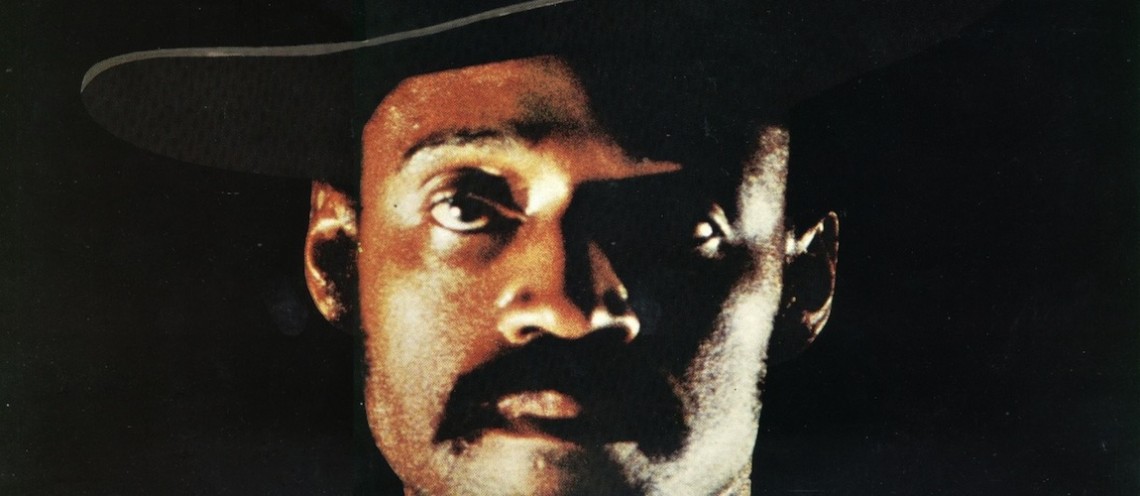

It was this same kind of bravado that emerged in 1971 with Melvin Van Peebles’ anarchic revenge fantasy Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song. As the popular story goes, this began the era of Pam Grier and funk soundtracks, a new genre’s urban grittiness and dismissal of white authority representing the natural end result of the failed optimism of the 1960s. Following this now-accepted thread of history, the birth of Blaxploitation placed black faces on screen while sounding the voices of African-American filmmakers who had previously been denied access to the white-dominated Hollywood system.

In the ensuing decades, Blaxploitation came to dominate how the critical and viewing community saw and defined black cinema and, to some extent, black life itself in the 1970s. This is a story so pervasive that popular awareness, let alone discussion, of a wide range of other films by and about African-Americans has been nearly nonexistent. In the decades since the ’70s, Blaxploitation’s style of machismo evolved into an institutional obfuscation of all other black films from the era.

It would be pointless to condemn any Hollywood genre for providing a false vision of its era. The main production institutions of any national cinema, be they the sprawling Shaw Brothers compounds 1960’s Hong Kong or Bombay’s present-day dream factories, exist to create and sell myths. Verisimilitude is the work of iconoclasts, not studios. But few eras and demographics are so closely linked as African-Americans of the ’70s and Blaxploitation.

A Google search for “black cinema of the 1970s” leads to page upon page of information on Blaxploitation. Four of the first five books visible in an Amazon search on the same topic focus specifically on the same genre. Though deeper studies of the era exist in the form of scholarships and books, most fold the ’70s into the larger context of cinematic evolution over many decades. But the equivocation of black cinema in the 1970s with Blaxploitation is troubling for another, less visible reason.

What single fact unites the Pam Grier vehicles Coffy, Foxy Brown, Friday Foster, and Black Mam White Mama? What commonality is shared by the crime pictures Black Caesar, DJ’s Revenge, and Detroit 9000? What about the women-in-prison film Savage Sisters and the martial arts pastiche Black Samurai, as well as Buck Town, The Monkey Hustle, The Mack, Mandingo, Death Dimension, Hammer, and Hit Man? Outside of their place within the Blaxploitation pantheon, every single one of these films was directed by a white man.

The same is true for many of the purely dramatic African-American films of the era, from Sounder, Black Klansman, and Claudine, to Cornbread Earl and Me and Lady Sings the Blues. Black people may have been on screen in the 1970s, and they may have held directorial roles in the likes of Gordon Parks, Melvin Van Peebles, Ivan Dixon, and Oscar Williams. But the genre most synonymous with African-Americans came largely at the hands of established members of the white Hollywood power structure. Subsequently, the genre that now most defines African-Americans in the 1970s reveals itself as one constructed largely by the impulses of white men.

The source of this institutional patina is similar to that of Bigger’s personal veil. Confronting the issues of an oppressed population, whether it’s done by that population itself or its oppressor, isn’t something that fills most people with enthusiasm. And lest we mistake the presence of these issues as a relic of Wright’s 1940s, or the 1970s, consider a section from Janet Mock’s recent Redefining Realness, in which she describes how her African-American family negotiated life in 1990s Dallas:

“They rarely talked about the unfairness of the world with the words that I use now with my social justice friends, words like intersectionality and equality, oppression and discrimination. They didn’t discuss those things because they were too busy living it, navigating it, surviving it.”

Even as those perpetuating oppression claim it does not exist, it must also be understood that those experiencing it might not necessarily want to define their lives through resisting it. Meanwhile, any artistic approach towards social reality is much more likely to be popularized through cartoonish excess or bloated melodrama, leaving us with Richard Roundtree blowing holes in honkeys while less explosive work, often by the same artist, goes unnoticed. But, reflecting an impulse visible in the recent trailer for Dear White People, there also exists a paucity of films about the experience of everyday people of color, those who are not criminal drug lords, runaway slaves or broad caricatures.

Marginalized artists in every era manage to find the means of production necessary to tell meaningful, personal stories, even if those stories often go unrecognized. We commonly talk about oppression through censorship, the repression of states like Mussolini’s Italy or post-Revolution Iran. Less discussed is passive oppression, the oppression of omission. Blaxploitation’s role as the dominant representation of African-Americans on and off the screen in the 1970s is a byproduct of selectivity in conversation, one that has left us with a sense that Superfly represents the totality of filmed black experience for a generation.

Blaxploitation allows us to look back on an era and feel like we understand it. Its tropes act as guideposts for the social, economic, and artistic factors that defined African-American life during the Nixon years. But a sense of immediate understanding can only be a curtain, deluding us into believing that just because we don’t know something happened, it must not exist.

Through this series, we will attempt to look past this curtain, investigating both the wonders of the films that lurk there, as well as the horror that accompanies the historical context surrounding them. We will look at the black students of UCLA who initiated the LA Revolution. We’ll spotlight the lesser-known films of African-American directors of the era, including alternative works from the key figures in Blaxploitation. We’ll look at how the careers of black movie stars of the 1970s were drowned out by their participation in the mainstream films of the 1980s. We’ll begin next week, with a look at the oddly rich history of black men portraying Klansmen.