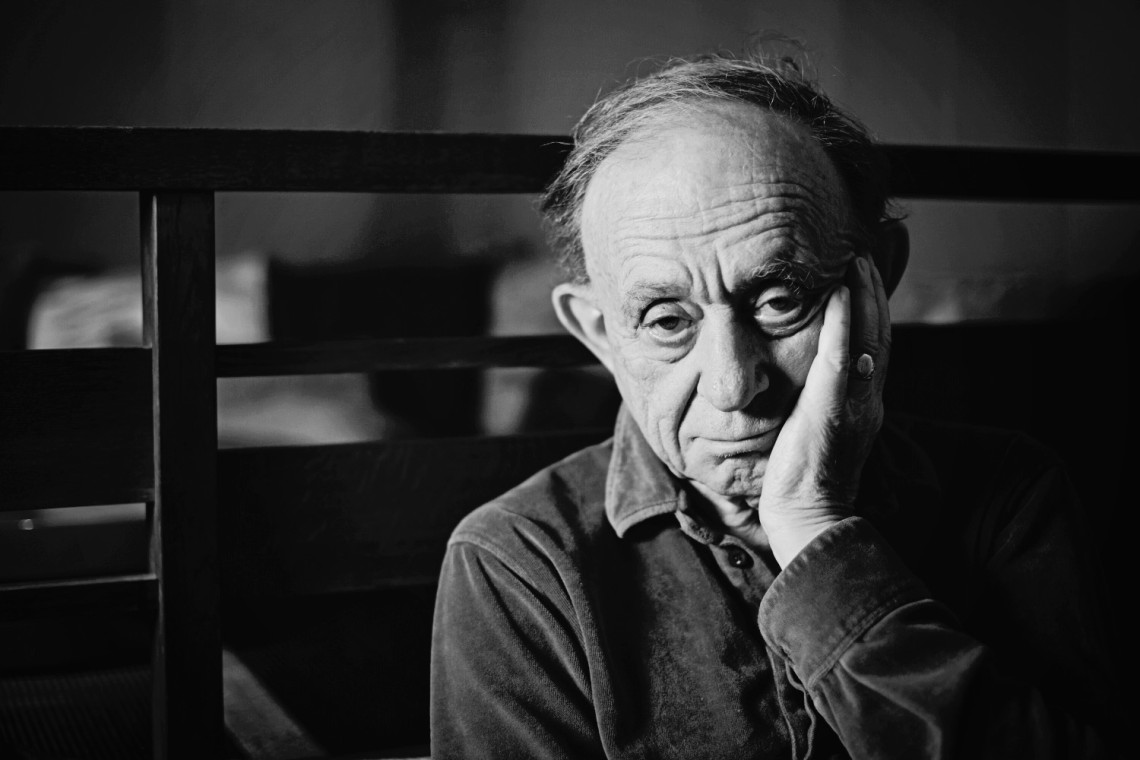

Recently awarded a Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement at the 71st Venice International Film Festival, 84-year old Frederick Wiseman has been directing (and producing) his films for more than half a decade, incessantly turning his perceptive gaze towards – predominantly – institutions. In his prolific portrayal of what could be simply summarized as America, he’s saturating things habitually perceived as transparent with significance, often discovering them as cruelly accurate mirrors of humanity.

Whoever was lucky enough to have a chance of seeing the accomplished filmmaker live knows how energetic and entertaining his presence is. Whether during a masterclass at the Zurich Film Festival (where the author had an opportunity of watching mr Wiseman talk about his work) or last years HBO Directors Dialogue series at NYFF, there’s no chance for Wiseman to keep his face straight for too long. Unforced and natural, he’s usually cracking his first joke in third answer the latest. It stands in somewhat of a contrast to common perception of his work – full of gravitas and importance, by many associated with direct cinema, because of its observational nature. But Wiseman, who finds his inspirations in the tangible tissue of everyday reality, is not keen on such comparisons (“cinema verité is just a pompous French term” – he said once) .

He’s an avid editor of the onscreen content, equally preoccupied with the truth as with the form of presentation, dramatic structure being one of his priorities. It wouldn’t be an overstatement to claim that Wiseman is THE American Documentary Filmmaker. At least from a perspective of someone, who wasn’t raised in the US his films are an open invitation to a complex inner world of american psyche, with all its wonders and flaws, a fascinating and challenging one. Wiseman’s artistic oeuvre consists of over forty feature docs. Here’s a subjective selection of the best (or most memorable) of them.

Meat (1976)

My first ever encounter with Wiseman’s work. Shot in Monfort Meat Factory in Colorado, “Meat” encapsulates the directors’ trademark style. Devoid of any off-screen, comforting narration, this meticulous recount of the multi-stage meat production process becomes a grim anthem, a visually powerful metaphor of society programmed to omit any uncomfortable cost of its growing consumerist needs. Almost forty years passed but Wiseman’s observations remain current, as many other filmmakers intrigued by the subject, for example Rober Kenner (“Food INC”), prove. Must-watch for any curious, conscious citizen, vegetarian or not.

Near Death (1989)

Before the brave Brittany Maynard brought the issue of choosing dying with dignity to public spotlight again in an extremely personal manner, there was “Near death” – Frederick Wiseman’s monumental 6-hour long documentary chronicling the work of medical intensive care unit at Boston’s Beth Israel Hospital. With the observing party present, but invisible, not forcing its point of view, it quietly follows patients’ extremely personal ultimate choices. What discerns this work from other, dealing with the subject of final departure, is that the moral or ethical layer is almost never an issue here. “Near death” protagonists, the hospital staff, are not wannabe miracle makers, filling in for God. They are used to facing and understanding hopelessness and the film supports them in stripping it of any ideological dimension. We are watching people who, with all their skill, tenderness and human weaknesses, are trained in making death easier, acceptable, understandable. Want to know what “sight and sound” means? Watch it.

The Store (1983)

This portrait of Dallas Neiman-Marcus department store is as methodically impeccable and informative as it gets, highlighting all the stages of product retail in this high-end company. Accidental, minor occurrences, clashing personal strategies, company practices made even weirder by the corporate context add humor and certain timelessness to the picture, turning it into a shining gem of Americana genre. With an unforgettable scene of hand and smile exercise – among many brilliant moments that effortlessly entertain – “The store” has sustained its sociological sharpness and validity despite the changing marketing and shopping strategies.

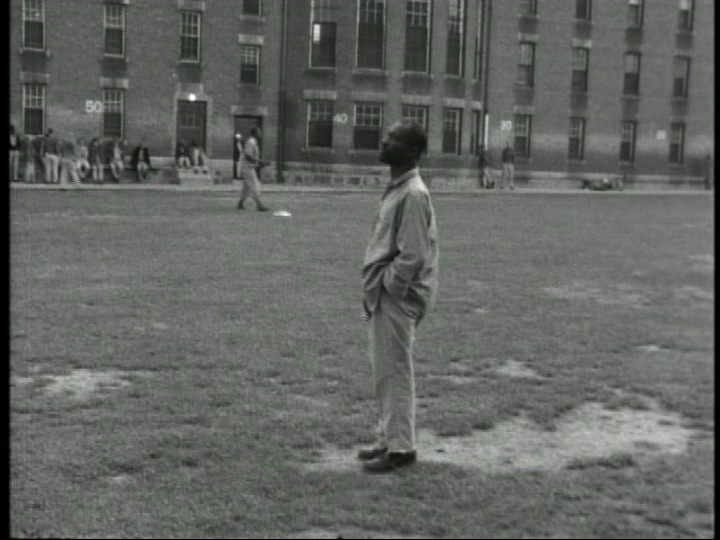

Titicut Follies (1967)

In his feature debut, Wiseman and his cameraman, John Marshall, filmed freely in State Prison for the Criminally Insane at Bridgewater, Massachusetts. Drastic and radical, the film doesn’t spare the viewer even the most horrific details of inmate’s day-to-day routines, exposing the rotten conduct of those in charge – guards, social workers, psychiatrists – who turn from protectors into persecutors. Identified by the authorities as a threat, this blatant accusation of a faulty system was banned by the Massachusets superior court based on „patients right to dignity” that the director – not the merciless guards, scolding and harassing the inmates – apparently violated. It was the first time a film has been banned on basis other than national security or obscenity. Unavailable for the general public until 1989, “Titicut Follies” is an invaluable time capsule, portraying reality that’s seemingly long gone – but the darkest, most shameful and common human emotions that it’s fuelled by are sadly eternal. Some aesthetic choices have aged, but what remains is a typically weismanian ability to allow superficially incompatible elements – silence and scream, power and helplessness, terror and joy – to seamlessly merge.

State Legislature (2007)

Filmed in 2004 during a 12-week session of the Idaho Legislature, this documentary is a spectacle of insanity, especially for someone from outside the US. 160 hour long footage was a lot even for Wiseman, who usually has to deal with excess of material (even 100 hours per movie) in the editing room. But as he duly noted, “politicians talk a lot”, and due to such predilection “State…” is also a very talk-dependent piece, contrary to Wiseman’s usual no-narration subtle strategies that might seem outmoded to those shaped by Michael’s Moore sensitivity. Deliberately inserted shock-factor is not Wiseman’s thing – here, as always, he strays from many “hot” subjects in the name of coherence and honesty. There’s a plethora of topics touched upon, from crucial to trivial. But somehow all the contrasting voices construct a cohesive entity, creating a very telling, universal dialogue about the world and humanity, despite the state level of events portrayed.