With Rian Johnson set to direct Star Wars Episode VIII, Internet response seems united in praise. He joins fellow “superfans” Gareth Edwards and Josh Trank, both attached to unspecified “Star Wars” spinoffs. It’s impossible to judge sequels to unmade sequels. But in the narrow range of choices at hand (all young, American genre filmmakers with short bios) the ensuing conversation is ignoring the one source of talent that seems most relevant to reinvigorating Star Wars. Because the perfect choice would needed to have come out of Hong Kong.

It’s impossible to say if George Lucas’ early film education exposed him to King Hu or the Shaw Brothers. Lucas, and others, have cited the influence on Star Wars of everyone from Akira Kurosawa to John Ford. Little to nothing exists, however, linking his space saga to the Chinese wuxia film. Whether or not Lucas was channeling these films, the similarities are unmistakable. Take 1967’s seminal Dragon Gate Inn. There is the isolated desert outpost teeming with danger and mysterious rogues. There is the evil empire, fronted by a menacing warlord with magic powers. When characters cross swords, they defy gravity with the practiced grace of trampoline assisted Peking opera. And beneath it all is an uplift, as if the film is infused with the same reckless energy that would enthrall Lucas’ audience a decade later.

Compare that tonal similarity to oft cited influences like Kurosawa’s The Hidden Fortress. The pair of bumbling peasants, a past his prime warrior, a plucky princess, serial style wipe edits. Taken piece by piece, the connection is noticeable. But the actual experience of watching The Hidden Fortress is different than that of watching Star Wars. Like most of Kurosawa’s mid period films, Hidden Fortress’s feet are planted in the cinematic soil. The black and white photography creates a subdued atmosphere. Its pacing is deliberate, its action scenes spare and realistic. It leaves the viewer with a sense of adventure but none of Star Wars’ fairy tale weightlessness. Compare the desperate violence of a Kurosawa scene with something like this scene from King Hu’s A Touch of Zen, and ask yourself which one you wish included laser swords.

By the time of Star Wars’ release, Chinese cinema had shifted. Its action films, had been overtaken by the hyper masculinity of Bruce Lee. Elaborate wire work persisted in films like Warriors of the Magic Mountain, but stateside audiences were more likely to find Yuen Woo Ping’s gravity bound choreography, the slapstick of Jackie Chan and Sammo Hung. Kurosawa, however, was primed for a late career comeback. As Kurosawa helmed the Lucas funded Kagemusha and the acclaimed Ran, the “Star Wars” trilogy unfolded alongside the creative reawakening of an established master, a coincidence in timing that allowed a series and a filmmaker to be inextricably linked in the popular consciousness.

King Hu, meanwhile, was still making the kinds of mystical adventure films that more closely resembled the spirit of Star Wars, while also alternating between melodramas and retellings of Chinese folk tales. But while Star Wars was gaining cultural acumen, the films of Hong Kong were doubling down on machismo. Even as the likes of Hu and Che Chang produce wuxia films throughout the 1980s, it was John Woo’s balletic violence that gained international popularity, while China’s Fifth Generation directors practiced a new degree of dramatic sophistication. Meanwhile, by the close of the prequel trilogy in 2005, Lucas’ once pseudo spiritual Jedi had morphed into veritable space ninjas, leaping about with all the dexterity of Chinese action stars and none of the gravitas. Here was the steady progression of a science fiction empire in the west, citing countless other western influenced while never mentioning its potential debt to the cinema of Hong Kong.

Much digital ink has also been spilled calling for the upcoming Star Wars installments to feature more female roles. In casting actresses both well-known and obscure, J.J. Abrams seems to have responded. But a few casting announcements could do little to bring the number of American female action characters to the level of China. From Ying Bai to Maggie Cheung to Li Bingbing, Hong Kong martial arts films have long featured women as central, powerful characters. For a culture imploring its tastemakers to feature women, little evidence for Chinese influence is needed than watching Zhang Ziyi square off againt Tony Leung in Wong Kar Wai’s The Grandmaster:

But now Wilson, Edwards and Trank stand poised to take control of the franchise. Such anglocentrism amidst increasing influence by the Chinese film industry makes it even odder that such a limited rubric is being applied to Star Wars’ creative lifeblood. Edwards’ single minded genre sensibilities especially indicate the type of unwritten restrictions much less common among Chinese directors. From Zhang Yimou to Ang Lee, the Chinese are visibly capable of moving between high genre and melodrama. Yimou in particular, much like King Hu before him, moves effortlessly from the wire work and swordplay of House of Flying Daggers (2004) to contemporary dramas like Riding Alone for Thousands of Miles (2005).

Consider Yimou’s images and their relationship with the iconography of Chinese cinema. In House of Flying Daggers, much as Ang Lee before him, Yimou borrowed from A Touch of Zen’s iconic bamboo and mist sword battle to create his films central sequences. With reclusive rebels posed in period dress, Yimou’s imagery wouldn’t be out of place in some far away galaxy.

Present too is that breathlessness that once defined the Star Wars series before its descent into George Lucas’ narcissism. From the empirical forces of evil to the charming rogue prince who undergoes a gradual transition into romantic sincerity, House of Flying Daggers feels more like a Star Wars film than anything made within the franchise since 1981. The same could be said for that most popular of western wuxia imports, Crouching Tiger Hidden Dragon, whose rooftop chases and reckless energy elicit the spirit of 1950’s adventure serials in a way that J.J. Abrams’ inevitably bloated, Harrison Ford injuring Episode 7 possibly can.

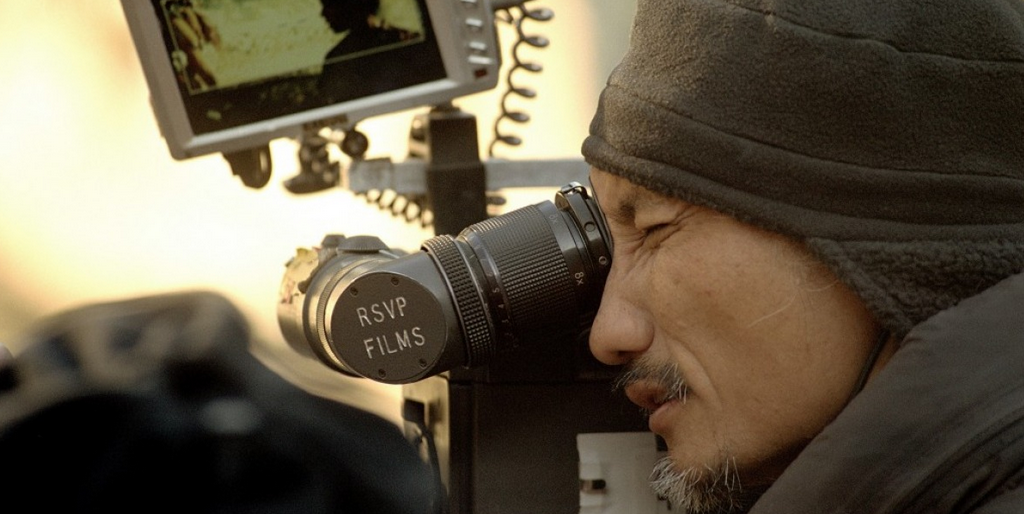

Given his current commitments, Yimou seems unlikely to appear attached to a Star Wars sequel. But what about Hark Tsui, Yuen Woo Ping, or even Ang Li? Limiting high profile directing opportunities seems counterproductive, especially as the future of Hollywood productions becomes more woven into their ability to succeed in the Chinese market. The very existence of not just an impending sequel trilogy, but Disney’s plan to milk the franchise for all its worth, demonstrates the increasing level of reliance studios place on established properties. We’re going to be getting a lot of Star Wars films whether we want them or not. So what if the spirit of mystical adventures and Zen warriors that existed years before Jedi or Wookies was not just recognized, but considered as a potential source of creative energy? Because somewhere out there, there’s a Chinese director just itching to get their hands on a lightsaber.

2 thoughts on “Why “Star Wars” Needs a Chinese Director”

I’m for this. I hope someone like Zhang Yimou would helm one of the “Star Wars” films just as long as he is given some control and be able to express his own ideas into the film.

Pingback: Star Wars: Original Trilogy to Make Big-Screen Debut in China