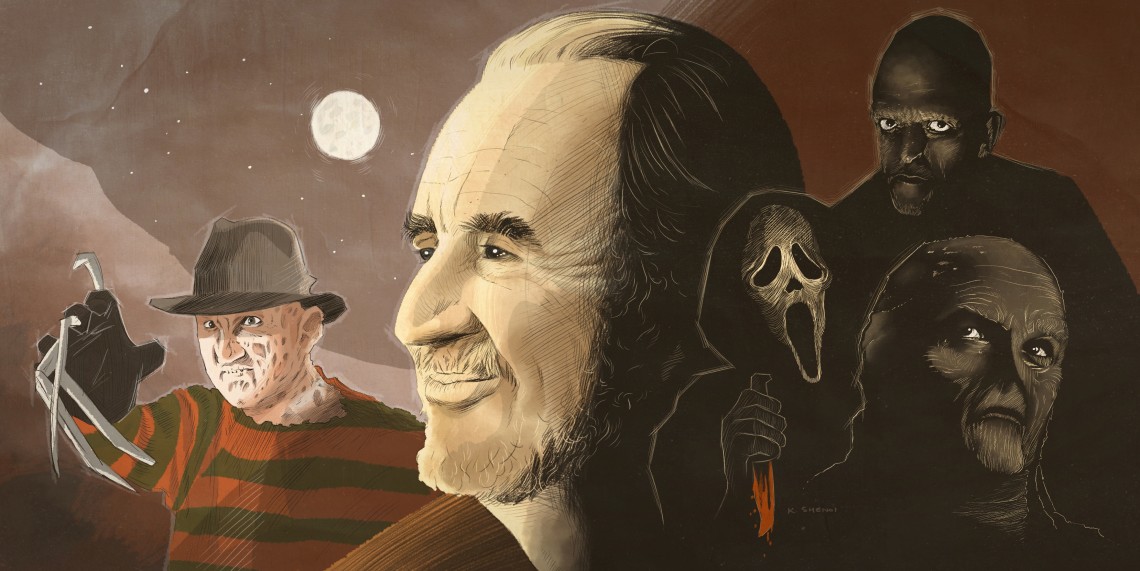

It’s clear from the outpouring of love after his death on August 30 that Wes Craven was not just a revered horror filmmaker, but also a pioneer in a kind of socially minded self-aware genre filmmaking that continues to flourish today. Before he made films, he was a humanities professor, and before that he grew up in a strict Baptist household. His first film jobs, however, saw him working behind the scenes in pornography. His unique background—a fertile mix of academia, religion, and smut—no doubt contributed to his unique and idiosyncratic vision.

Most of Craven’s early work is rough: difficult to watch, and held together only by grit and mud. The impact of films like The Last House on the Left (1972) and The Hills Have Eyes (1977) came both from their documentary spirit and the strength of the ideas behind them. Though both films are marred by weak character writing and poor performances, such drawbacks do little to undermine the films’ brute visceral impact, especially when considering the time in which they arose. The 1970s was a decade reeling from the failed Vietnam War, the senseless brutality of the Manson murders, and the disillusionment with the hippie movement. Craven’s early work fully reflects this troubled era: tearing apart the wishful dream of safe and comfortable life in the country, confronting the audience with a less palatable version of the American dream. The double-edged sword of The Last House on the Left in particular showcases both an (arguably) unwarranted sadism and a credible revenge story; the film’s sheer existence attests to its potency as an attack on the status quo.

Above all else, though, these early works show Craven’s interest in bending reality. These movies stylistically borrow from the documentary, with rough handheld cameras and 16mm bringing a sense of grim realism to the proceedings. Narratively and aesthetically, these films are rooted in the idea that nightmares can invade real life. The horrors of The Last House on the Left and The Hills Have Eyes come from, respectively, a senseless invasion of violence into the life of a teenage girl and a family on vacation. In both cases, the characters find themselves confronted with evil they have never been forced to contemplate before.

Craven’s desire to confront the horrors of reality would feed into his most notable contribution to the horror genre, A Nightmare on Elm Street (1984). With Freddy Krueger, a burn victim with claws for hands, Craven brought nightmares to life and helped reinvent the horror genre in the process. Released at the apex of teen-slasher wave, the film broke expectations that had already been established by films like Halloween and Friday the 13th. While both of those series featured villains who were more monster than human, the situations remained rooted in some sense of reality; by contrast, the majority of the horror in A Nightmare on Elm Street unfolds in the human subconscious. Not only does this grant Craven more imaginative freedom, it also allows him to tap into universal fears. There is something primally frightening about the idea of dreams coming to life, because they can almost be remnants of previous lives—and in this case, as the haunting of Freddy Krueger comes from the errors of the parents who burned him to death in a fit of vigilante justice, fear itself becomes hereditary. Craven thereby taps into the essence of great horror, conceiving a tale that allowed him, and us, to explore the disturbing hidden depths of our humanity.

The gimmick of using dreams was also more pointedly about horror and storytelling itself than previous horror films had dared. This vehicle would allow audiences to feel both “in the know,” aware of the genre conventions while still being able to be surprised by them. Dreams and nightmares were the perfect vehicles to bend the rules of real life and create unique phantasmagorical images that would make George Méliès proud.

Nearly 10 years after A Nightmare on Elm Street—and after having flirted with meta-movie horror two years before in Wes Craven’s New Nightmare (1994)—Craven would shake up the horror genre once again with Scream (1996). The fact that you had a character within the film explaining beat-by-beat the tropes of the horror genre, just as the oblivious cast was slowly murdered off, was delirious irony. Audiences ate it up: They felt smart because they recognized the patterns of the genre, and they were even more enthused that, despite this knowledge, Craven still found ways to shock them. It was the updated campfire story, a horror film about horror films that cemented the social aspect of storytelling.

With Scream in particular, Wes Craven explores the communal experience of watching horror films. This is far different than the fan engagement of something like The Rocky Horror Picture Show; instead, Craven was pointing out that we use stories to work through our problems. Instead of merely regurgitating the typical horror beats, Scream revealed the genre’s sociological implications through its clever deconstruction. This is especially evident in the film’s treatment of virginity as it ties to virtue. In slasher films like Halloween, the message was clear: have premarital sex and suffer the deadly consequences. Scream actively tries to dispute this formula, and thereby suggests a huge shift in the sexual autonomy of Craven’s women. Whereas in The Last House on the Left, women were little more than props in a greater narrative, in Scream, the women are no longer defined by their bodies and are able to take control over their sexuality.

Sandwiched in between Craven’s best-known works are many little gems. Swamp Thing (1982) is endearingly terrible, a wonderful and never-boring camp exercise. The Serpent and the Rainbow (1988) is somewhat uneven, but a great example of Craven blurring the lines between reality and fiction, as the film is based on a nonfiction book about the Haitian voodoo culture. And perhaps the best of his lesser-loved works, The People Under the Stairs (1991) is a great horror film for and about children. That film, in particular, is an excellent example of Craven’s social consciousness, as he rooted the film in the experience of black children in the Los Angeles ghetto.

In nearly every decade of his career, Wes Craven was able to surprise and delight a generation of filmgoers with something they’ve never seen before. His best films don’t exist in a vacuum and are deeply entrenched in the fears and concerns of the times during which they are released. One of his greatest assets as an artist was his ability to grow with his audiences and to consistently push the boundaries of horror cinema. With his death, the horror community has lost one of its brightest lights.

—

Original illustration by Krishna Shenoi.

5 thoughts on “Wes Craven: In Memoriam”

That was a great commentary and informative synopsis of Craven’s career. I take issue somewhat with your take on “Halloween,” however.

The protagonist is indeed a virginal girl, but unlike the less “virtuous” females in the movie, ultimately “Laurie” refused to be a victim and had the courage and fortitude to fight back.

Perhaps the message was not that premarital sex was wrong per se, but that “Laurie’s” decision to be true to herself and not succumb to sexual desire at that point in her life reflected a strength of character worthy of respect.

Hi Greg, thanks for the comment.

I don’t disagree with your assesement of Halloween at all – I would even argue that I was possibly a bit lazy in using the example, because as a stand-alone I think that it’s not about the evils of sex and Laurie’s virginity is not virtuous – her choices are. Initially I named more films, but I scaled back for clarity. I think Halloween is representative of a trend related to sexuality, one that does see promiscuity “punished”. That doesn’t mean this individual film has a huge problem, but there is certainly a trend moving in that direction.

The example I’d use to explain what I mean is the Bechdel test. Just because a film fails the test, doesn’t mean it’s a bad film, it doesn’t mean it would be improved if it followed the formula – it doesn’t even mean a film can’t be feminist if it doesn’t “pass the test”, but it’s about a larger trend that is problematic when you look at a group of movies. Now, perhaps you’re right and I chose a poor example, but I do think Halloween’s take on virtue while more complex than maybe I insinuated is still pretty basic. Some slashers, including it’s precedent Black Christmas, offer a far more interesting take on virtue and sexuality (though to be fair, the virgin gets it first in this case too).

I appreciate the comment, and in the future I will certainly try not to use a single film as an emblematic example of larger trends as maybe I did here.

Hello Justine:

I love that “Bechdel” test! And from what I can recall, “Halloween” certainly fails that test. Sadly, I would imagine that’s true of many – if not most – films, however. No surprise, since I’d wager most script-writers who see their stories brought to the screen are (young) men.

I appreciate your thoughtful reply. And I don’t think you picked a poor example. It just happens to be a personal favorite of mine. If you had inserted “Friday the 13th” in place of “Halloween,” I’m certain I wouldn’t have had my feathers ruffled!

I think it’s fair to say Carpenter’s movie is widely-regarded as a cult or genre classic, if not an outright classic – due undoubtedly to the superior filmmaking on display compared to most low-budget slasher entries of the period.

At any rate, I truly admired your article, both in terms of form and content. I look forward to reading more!

Pingback: September in Review | Beyond the Red Room

Pingback: Film Writing 2015 | Beyond the Red Room