Editor’s note: We are thrilled to announce that MUBI, the curated online cinema that brings its members a hand-picked selection of the best independent, international, and classic films, is sponsoring Movie Mezzanine. You can use the discount on this promo page to check out all of MUBI’s selections.

Within the dour, solemn genre of the gangster movie exists an even more po-faced variant in the story of the gangster trying to go straight, to leave behind a life of crime and be legitimate. The Godfather saga is the most protracted example, an opera seria that first charts Michael Corleone’s moral downfall before tracking the empty ways in which he tries to buy his way to redemption. The first act of Takeshi Kitano’s Sonatine loosely fits into this tradition, but instead of drawing drama from its protagonist’s desire to leave a life of crime, the film finds great comedy in the absurdity of a violent man’s deluded belief in normalcy.

Known in his homeland as much for his zany television appearances as his deadpan Yakuza films, Kitano does not suppress his comic tendencies with the film so much as sublimate them into the droll facial expressions of Murakawa, a Yakuza enforcer who has grown weary of his life. Wearing a look of perpetual bemusement, Murakawa’s blank face could be read as either suppressed rage or profound boredom, more likely a combination of the two. Easing his way toward legitimacy, Murakawa runs his loan shark operation out of a modest office space that could pass for a real business, at least until associates who man the phones burst into furious invective on the deadbeats who call begging for relief.

The occupational violence has become tedious rota, and in one scene, Murakawa and his goons drag a lendee out to the waterfront and lower him into the bay, the camera focused on the rope to which he is attached, as a crane pushes him deeper and deeper. After an agonizing length of time, they raise the man, whose limp form somehow surprises Murakawa. “Boy, we killed him,” he says, with all the emotion one uses to realize they left a light on in the house. After a moment’s pause, he shrugs and tells his men, “It doesn’t matter, cover it up.” Kitano plays up this complete acclimation to violence as proof that Murakawa’s thoughts of leaving the mob are ridiculous. When a transparently set-up assignment goes south and erupts in a bar shootout, both sides crouch behind cover and trade volleys, but Murakawa stands completely in view, pulling the trigger of his pistol with eerie calm as the room explodes around him.

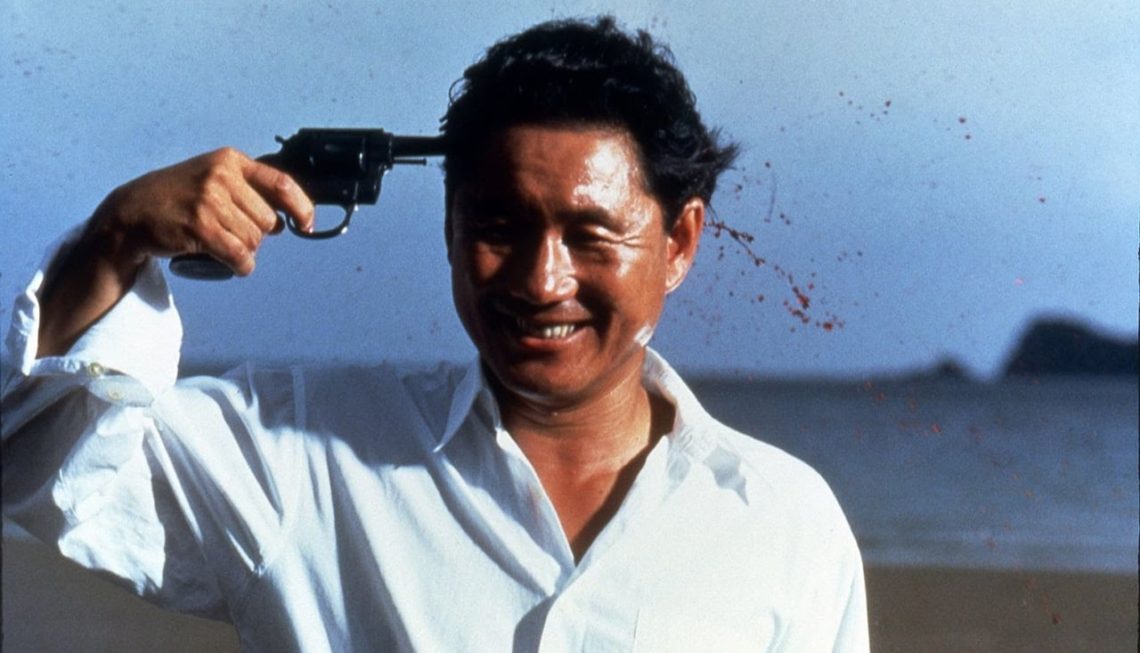

Fleeing this massacre, the loan shark and his men hole up in a beach house to lay low, at which point all thoughts of normalcy collapse and give way to a kind of riff on Lord of the Flies. No sooner do the men arrive than they start to come up with ways to amuse themselves, shooting beer cans off each other’s heads and playing games of Russian roulette. This is not a regression to a primal state so much as a showcase of the men’s primitivism without its usual targets. Murakawa even smiles a little in this bacchanal, smiling with glee as he joins in a mock shootout with Roman candles with his actual pistol, firing wildly with childish glee as his men duck and cover and beg him to stop, less out of fear than annoyance that the game has been disrupted.

The mildly disturbing nature of the dangerous immaturity deepens as the full extent of Murakawa’s anhedonia. One night, he spots a man preparing to rape a woman (Aya Kokumai) and watches without emotion, stopping the act merely by walking past nonchalantly and distracting the rapist. The man attacks Murakawa, perhaps out of annoyance more than panic, only to receive a few bullets for his cheek. When the woman does not give thanks or grovel but instead silently joins his band of fools, Murakawa seems surprised, as if he is used to the usual exchange of violence and loyalty but when it comes with such genuine humility and unforced reciprocity.

Sonatine eventually sinks into the kind of dead-end realization that most of these films reach, that grim anti-epiphany that escape is not possible and that death is the only release from a life of crime. But even so the film never plays this understanding for miserable reflection but callous dark comedy. It’s telling that the most cathartic and exciting moments are the outbursts of gunfire, precisely because they feel so natural to the men and especially to Murakawa. They are the times that he feels comfortable with himself; everything else is merely denial. Even the somber conclusion has an odd sense of humor to it, precipitated by rapid-fire scenes of bloodletting that may be the travesty that puts the writing on the wall in blood, or maybe it’s just one orgiastic death fantasy that inspires the final action.

If you’re interesting in watching Sonatine on MUBI, use your Movie Mezzanine coupon for an exclusive discount and access to a breathtaking library of cinema!