Editor’s note: We are thrilled to announce that MUBI, the curated online cinema that brings its members a hand-picked selection of the best independent, international, and classic films, is sponsoring Movie Mezzanine. You can use the discount on this promo page to check out all of MUBI’s selections.

The common refrain on Muhammad Ali in the wake of his passing is that he was, indisputably, the greatest boxer of all time, and that his greatest fights occurred outside the ring. It is a clichéd notion, but sometimes clichés are true, and this premise forms the backbone of Bill Siegel’s The Trials of Muhammad Ali. An overview of the fighter’s public life, the documentary looks at his many famous bouts only in the context of the controversy and media firestorm. This framing choice suggests that Ali’s occupation merely provided the focal point for his most important cultural work.

The film’s first image comes from a 1968 taping of The Eamonn Andrews Show in London, in which Ali, then unable to leave the United States, appears via satellite and is shown on a television set placed in front of the host and gathered guests. This image of Ali being on television, while on television, is a succinct summary of his massive celebrity, and most especially how even at his professional low he commanded media attention. This clip introduces the tensions that plagued Ali at the time, forcing him to be tried in absentia by a panel of American guests who lob insults at him for his refusal to be drafted, but from there, Siegel leaps back to Ali’s popular emergence to show the many factors that led to this moment.

The earliest point in the documentary’s chronology introduces the young amateur boxer Cassius Clay as he returns from the 1960 Olympics in Rome with a gold medal around his neck. In interviews with the press, he speaks of his desire to go pro, remarking that he will assemble a management team from his Louisville hometown. Undermining that sense of neighborhood pride, however, is the fact that Ali’s backers are a group of white businessmen, whose money (and, of course, skin color) affords them access to the boxing commissions that would book the fighter. Of the group, only Gordon B. Davidson is still alive—“I’m the last survivor,” he says morbidly”—and even now his tone is paternal, kind and wistful but revealing of a perspective of looking after the champ instead of fully understanding him.

Contrasted with this white-led entrance into the big time is the young Clay’s exposure to Islam, an exposure that coincided with his increasingly vocal opinions about race. Members of the Nation of Islam who courted Clay recall his conversion process, and especially the reaction of the general public to his new religion and name. Siegel subtly plays up this conflict; the film does not spend any time delving into the slew of white boxers fed to Ali in an attempt to topple this loudmouthed, proud champion, but it is clear that he is constantly thwarting attempts to see him fail. Even the subject of his name becomes a constant battle, with reporters and opponents refusing to acknowledge him as such and commissions refusing to book him under his name unless he got it legally changed in a dog-whistle attacks on his race and religion. (As sportswriter Robert Lipsyte notes, no one ever harassed John Wayne about his real name.)

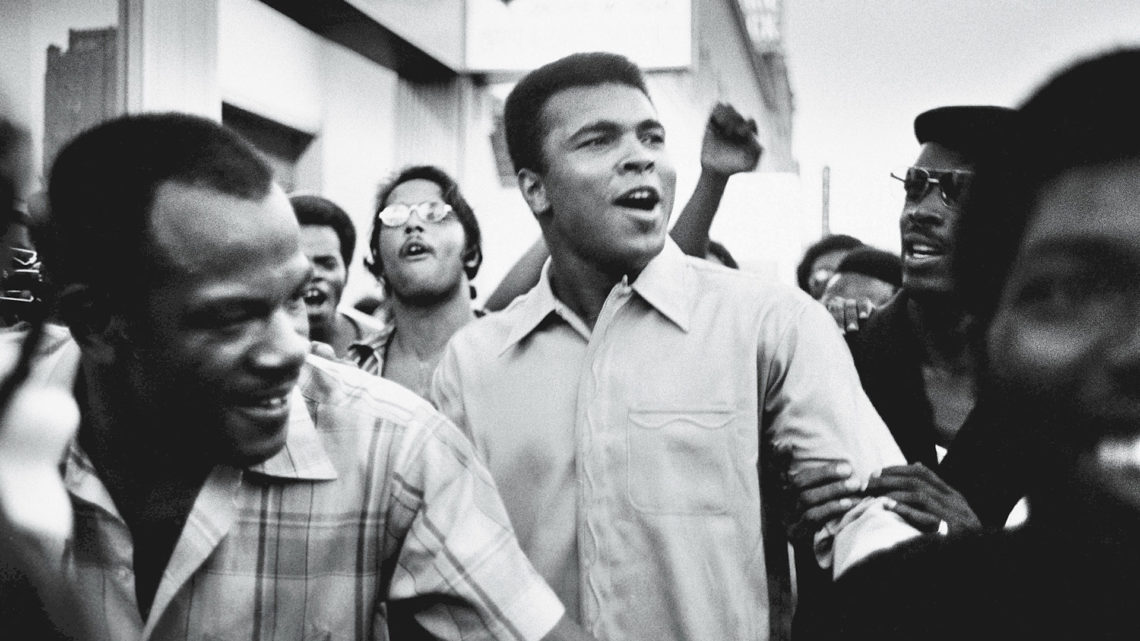

Assembled in retrospect, it is easier to see these hassles for what they were, and the image of Ali the angry, militant figure seemingly shadowboxing at vast conspiracies to hold him down, now looks rational and shrewd. By the same token, the film’s greatest achievement is restoring some of the radical context to a man who long ago became a universally beloved icon. The Vietnam War is now so thoroughly accepted as a colossal mistake that those who refused to serve catch no real grief, but here, one can see what it truly cost Ali to stand up to the draft. This is a man who had the options afforded to the rich, of getting plush, perfunctory terms in reserves where he could not only avoid action but even get a media boost for his “service.” Instead, he publicly scorned a trumped-up war and refused to lend his name to a conflict being fought in the name of humanitarian anti-communism while the streets of America burned. Images of newspapers that editorialize even in their headlines, caricaturing Ali as an entitled coward, blur with the voices of prototypical pundits like William F Buckley, Jr., who invites Ali to an episode of Firing Line and talks to the man with simpering condescension. The film reminds the viewer that Ali lost nearly everything: his titles, the chance to make a livelihood in his prime, millions of dollars. But in these moments, it also shows an attempted character assassination that could have ruined him forever.

It didn’t work, of course. Returning to the first image of the documentary, Ali was only beamed into talk shows in the first place precisely because he weaponized his exile. Instead of laying low or falling apart, the champ, at the urging of second wife Khalilah Camacho-Ali (still full of fire even in her contemporary talking heads), met the controversy head-on and turned it into another fight. If the blatant thesis of the film is that Ali’s most important battle occurred in both legal courts and the court of public opinion, its subtler message is that Ali is the figure he is today because he excelled so brilliantly at becoming a political figure. Siegel does not go into Ali’s return or the epic bouts that sent him back to the top, because those are incidental. The real fight had been won the second that the Supreme Court had to contend with the case of a man who had become a figurehead for millions, not only in this country but around the globe. Many plaudits have been justifiably written for the man in the last week, but The Trials of Muhammad Ali lets you see firsthand how he earned them, not to mention how many of those spilling ink in their effusive praise of the fighter might have been among those who buried him at the time.

If you’re interesting in watching The Trials of Muhammad Ali on MUBI, use your Movie Mezzanine coupon for an exclusive discount and access to a breathtaking library of cinema! Note: MUBI now offers its streaming service to North American users via a Playstation 4 app. Visit the Playstation Store to download for free.