The Movie Mezzanine Filmmaker Retrospective series takes on an entire body of work–be it director’s, screenwriter’s, or otherwise–and analyzes each portion of the filmography. By the final post of a retrospective, there will be a better understanding of the filmmaker in question, the central themes that connect his/her works, and what they each represent within the larger context of his/her career. This time, we’re going to examine the decades-spanning career of one of the most important filmmakers of this generation and generations prior: Terrence Malick.

…

Terrence Malick was back in business. After his legendary two-decade disappearance, he had returned to filmmaking with The Thin Red Line, his epic anti-war film set against the backdrop of the battle for Hill 210 in Guadalcanal during World War II. And as you can imagine for this kind of comeback, everyone asked the same question after the film was nominated for seven Oscars and the future was staring all Malick admirers in the face: What’s next?

Considering his first two films were rather small in scale and length (Both were around 90 minutes), and he followed those up with a nearly 3-hour epic, it was guaranteed that whatever his next project was, it was gonna be an interesting decision.

Yet even with that anticipation, a historical adaptation of the story of John Smith and Pocahontas was unexpected. Everyone still considered Disney’s Pocahontas film to be the definitive cinematic version of that story, even if it was as far removed from the reality of that historical event as you can get from Disney, so the prospect of seeing a more realistic and mature version of that story must have been a big “Oh, why didn’t I think of that?!” moment for hundreds of filmmakers first hearing about it.

And with The New World‘s release, it felt as if the pattern of Terrence Malick’s past was repeating itself. The Thin Red Line received near-unanimous praise upon its release–with the Academy Award nominations to further prove it–much in the same way that Badlands was met with universal acclaim when it first released. And with The New World, the pattern seemingly returned, as the film was met with heavily divisive responses from critics and audiences alike; much in the same way that Days of Heaven was introduced to with its initial release. And just like Days of Heaven, its stature as a truly masterful film has only grown with time.

It is in this New World that The Terrence Malick Retrospective continues with his 2005 film The New World, as we dissect what makes it a fascinating evolution of Malick’s signature themes. It should be noted that this essay contains spoilers, but considering this is based on events that have already happened and are in every history book, it really won’t kill anybody to read this without having seen the film.

…

“A world equal to our hopes. A land where one might wash one’s soul pure. Rise to one’s true stature. We shall make a new start, a fresh beginning. Here, the blessings of the Earth are bestowed upon all.”

The Thin Red Line began with AWOL soldier Private Witt (Jim Caviezel) living amongst the Melanesians in a remote village in Guadalcanal. About 5 minutes into the film, he’s whisked away from that peaceful Eden and sent to fight for the control of Hill 210. He is told by one of his superiors, Sergeant Welsh (Sean Penn), that in this world, a man is nothing. “And there ain’t no world but this one…,” he continued. And Witt responds with this rather poetic line regarding his brief time living with the Melanesians: “I seen another world. Sometimes I think it was just my imagination.”

Indeed, there is another world out there. There are actually many like it. And for John Smith, that New World was the freshly discovered America. As he wades through its untainted fields and forests, befriends the Algonquian-speaking Native Americans, and falls in love with Pocahontas, he is at peace. And when those days of heaven finally end and he’s brought back to the Jamestown colony, he says to himself in one of his numerous monologues, “It was a dream. Now I am awake.” He did see that New World. And yet it was so alive and at the same time entirely foreign to him that he sometimes thinks it was just his imagination, much like Private Witt remembering how he swam in the ocean with the Melanesians.

In that sense, The New World is very much a companion piece to The Thin Red Line. Sure, all of Malick’s films are about these Edenic Gardens that can never be conjured up again once they’re destroyed, but both The Thin Red Line and The New World carry a strange connection.

On the surface, they’re both historical epics, they both depict their Edens as peaceful villages at one with nature, and they both later depict the destruction of that very nature all throughout their film. But underneath those exterior similarities is this notion that this Eden becomes nothing more than a dream once it’s gone. Whereas Badlands and Days of Heaven depicted a paradise lost and alive only in memory, the characters of both The Thin Red Line and The New World are separated from paradise not only by time, but by existence as well.

These Edens take on almost mythic, Biblical statures–and that’s saying something considering the locusts and flames that plagued the wheat fields of Malick’s Days of Heaven. These places might as well exist in the afterlife from now on, and as the death scenes of both Private Witt and even Pocahontas indicate in their respective films, that may very well be the case.

Indeed, the line is used again when Smith sees various settlers attempting to mine for gold, and he stops them with the line “If there’s so much gold here, why don’t the naturals have any? You are chasing a dream!” All of Malick’s characters in every one of his films seem to be chasing some sort of dream; some kind of Eden that brings them back to a time of innocence, like the lovers on the run in Badlands and Days of Heaven, or the soldiers in The Thin Red Line.

In the case of The New World, this dream is more distinctly linked to the land they step on. This New World they’ve encountered doesn’t seem to represent an innocence of the past. Rather, it represents an opportunity for the future. For Smith, he wishes to remain as peaceful as he did upon first encountering the Natives. For the various settlers, it’s the wish to be free from the constraints of their original country. For all, it is the chance of starting anew; to cleanse their soul and start from square one. Thus, the dream of The New World becomes more than just a figment of their imaginations. It is both that and a mirage at the distance representing promises fulfilled. Not of the past, but of the future.

And here it becomes achingly clear. This is Malick’s rumination of “The American Dream”.

“There is only this. All else is unreal.”

And it is this American Dream that consumes the hearts of every individual inhabiting the New World, transforming the relationship of the Natives and the Colonists into an all-out war for their personal Edens and American Dreams. Like all Malick films, Eden is destroyed not by forces beyond man’s comprehension, but through man’s own selfishness and sinfulness; to the point that even the innocents with nothing to do with these men’s actions become victims in their bloodshed, tarnished forever by the wrongdoings of their elders like every child born with the burden of Adam and Eve’s original sin.

Yet as Malick chronicles the constant struggle between the settlers and the Natives, he never once picks sides, even when he does contrast the beauty of the Native American villages with the barren ugliness of the colony. Malick always favors the natural world over the world of men, yet he also happens to acknowledge that it is this barren, gray Jamestown settlement that made way for the nation that would eventually become the America we live in today.

In fact, The New World might be the only Malick film that actually reconciles with the fact that Eden must be abandoned sometimes in order to progress further as a society, rather than just lamenting its loss over the entire running time. That makes it an interesting development in the Malick canon. His signature elegiac tone remains, but it’s now laced with hope for the future. The Eden of old may be gone, but they may be able to construct something else from its ashes–and maybe it is we who are still carrying on that tradition.

Though, to be fair, Malick still makes it entirely clear that the America of Old can never be replicated again. As always in his films, there’s no going back to the Garden for Adam, Eve, or all their children of the future. And there’s certainly plenty of lamenting to be had in the film. But when all of that is said and done, there is that hope that something great–yet completely different–can be made of this loss. You can argue for yourself whether the America of Today is worth the destruction of the one of Old, but in the film’s timeless vacuum, there remains a promise that humanity can make good on its sacrifices.

Of course, there’s really one element that embodies this transformation from grief to optimism that the film wouldn’t have been able to work without: Q’Orianka Kilcher.

“She weaves all things together […] All sings to her.”

Kilcher is to The New World as Linda Manz was to Days of Heaven: A thread that keeps every thematic element tied into one unified whole. Not only does she effortlessly convey her natural synchronization with the earth surrounding her, she’s also an embodiment of all the various struggles throughout the film: The settlers vs. the natives, the sadness of losing the past vs. the hope of a brighter future, and the path of nature vs. the path of fate.

It is through her that the film’s various shifts end up working. Like, for example, when John Smith is all but abandoned for the film’s second half, and John Rolfe enters the picture. If not for her performance to carry us through the two entirely different love-interests, the switch would’ve been more jarring.

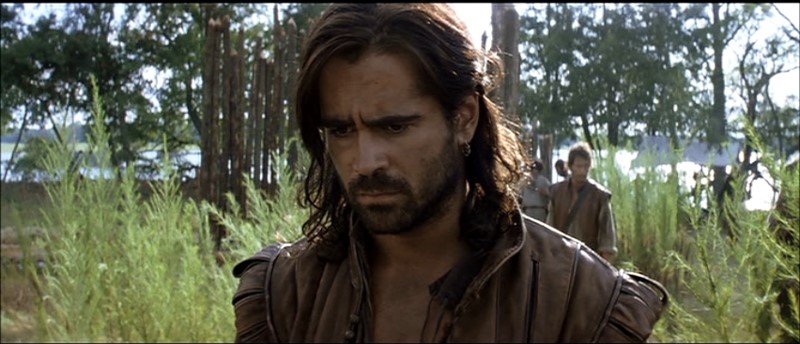

Her performance also helps really establish the romantic encounters in general. When she first meets Colin Farrell, they do not know each other’s language and as a result, create a wordless bond that’s only bridged when the two exchange the meanings of words in their respective languages. A scene such as that wouldn’t work if not for the 100% sincerity of the actors, but here it truly does feel like they’re discovering something new.

That’s a compliment that can be made for the entirety of The New World. Malick manages to do something I never thought possible, and that’s make America seem like a New World to begin with. The fact that he does this not through visual tricks or alien production design, but with nothing except an abstract sense of discovery–something that’s impossible to really grasp on a concrete level–is a startling and wondrous thing to behold on screen. This is a movie that works with a kind of unexplainable magic. You can’t really point your finger on just how Malick managed to create this sense of wonder. He just exudes it naturally. Like him or not, he may be the only filmmaker who can do that.

The film as a whole is all about this sense of discovery; not just for the Americans, but for the Natives as well. And while John Smith had to bring the Original Sin of the advanced civilizations to the Garden of Eden, it also allowed for progress to reach that land as well. Furthermore, while Eden was tarnished, Pocahontas’s innocence from that era was never lost, and she becomes a vessel through which the kindness and freedom of that paradise can be transferred to her New World, making sure that it never dies, even when it is in ruins.

“I thought it was a dream… What we knew in the forest… It’s the only truth.”

And indeed, there is a moment when Pocahontas, renamed Rebecca when she marries James Rolfe, is on the brink of death. Rather than writing my own words on the final scenes of the film, it should be noted that Scott Tobias of the AV Club summed it up better than I ever could. So here’s a direct quote from his New Cult Canon write-up…

“The New World’s tone cannot be described as mournful, because beauty, love, and the miracles of life persist even amid death and destruction. Pocahontas dies at the end of The New World, but there are no rending of garments, no efforts to underline the tragedy of her story. The film opens and closes with the same images: water rippling, birds chirping, trees shimmering in the sun. Life goes on.”

One of Malick’s main obsessions has always been man’s place and importance in the grand scheme of the universe, but what does this final moment say about an individual’s place in history? Pocahontas planted the seed of kindness for the New World in much the same way that she gave the English the seeds for which crops to grow in their Jamestown settlement. (She is both the Tree of Life and the Tree of Knowledge, in this case). As evidenced today, she is as important a figure of American and British history as any other. And yet, the world doesn’t rest for her. She is just another tool of history; another pawn of destiny.

While it’s considered today that there are no New Worlds left, Malick seems to state that there’s always more out there waiting to be discovered. “How many lands behind me?” John Smith asks as he’s venturing through his New World. “How many seas?” For him, that sense of wonder and discovery for the world remains. As he’s first wading through its rivers and brushing up against its foliage, the New World might as well be infinite.

Yet by the time we’ve reached around the halfway point, that wonder has been completely evaporated; to the point that even the woman he loved precisely because she represented this New World, has conformed to the ways of his Old World by the film’s end. As he says later on in the film, “There is nothing but this”. And yet, at the same time, there isn’t. There are still stars in the sky that he has yet to look up at. There are still places uncharted beyond the eastern coast of his Indies. There are still centuries of technological progress left before he can realize how truly small he is.

No matter how much he explores, there will always be a New World.

Maybe every curvature of the earth has been charted out by geologists of every century. Maybe all the lost civilizations of myth have been discovered or debunked. Maybe there are no Great Wonders of the World as we’re lead to believe. Even still, there’s always more to discover. Of the world. Of human nature. Of the kindness of others. Of the cruelty of this species. All that’s important is to never stop exploring. Even if it means crossing the edge of this world. Or the next.

“Mother… Now I know where you live.”

Audiences apparently didn’t want to be transported to The New World, for it grossed only $12.7 million over the course of months. That plus its divisive response from both audiences and critics didn’t help alleviate things much.

As stated before, the pattern seemed to be repeating itself, with The New World being the Days of Heaven misunderstood “failure” that The Thin Red Line was to Badlands‘s universally praised classic. Did this mean another 20-year absence from the legendary Terrence Malick? Far from it.

Tune in next time, as we follow Pocahontas and John Smith’s footsteps by exploring a New World of our very own: The cosmos and spiritual kingdoms of what many consider to be the ultimate Terrence Malick film, The Tree of Life.

Previous Editions:

3 thoughts on “The Terrence Malick Retrospective: The New World”

That was beautiful. A film that didn’t get its due when it first came out yet I was one of those who saw the 135-minute theatrical cut when it played in theaters and just fell in love with it. I bought that version as well as the extended 172-minute version of the film which is just as great though there’s not really much difference between those 2 cuts as the longer version was a combination between the 135-minute general release cut and the 150-minute Oscar cut. BTW, which version of the film did you see?

I saw the 172-minute Extended Cut on Blu. It’s terrific.

Pingback: The New World (Terrence Malick, USA/Great Britain, 2005) – Vanguard Cinema